Words & Photographs: Stan | Archive Images: Pat Joynt

The relationship between Vietnam and the humble scooter is as complicated as the history of the country itself. Here Stan explains the ‘Nammer’ story.

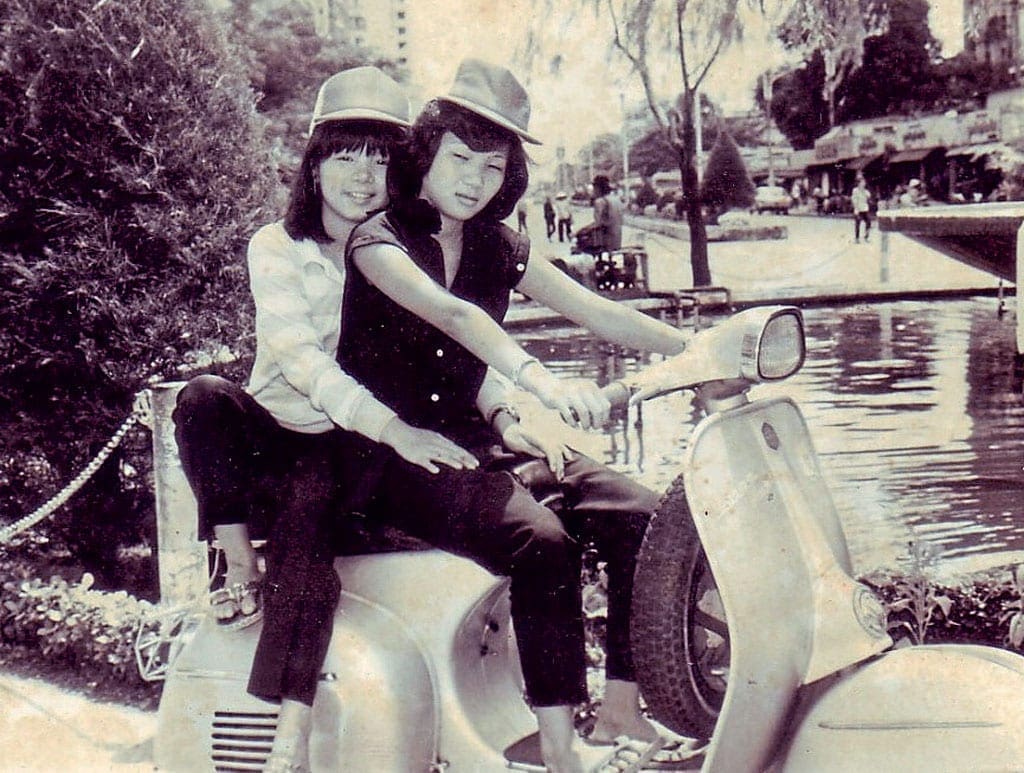

It’s said that there are more scooters than people in Saigon and it’s a statistic that’s easy to believe when you see it for yourself. Today the city’s filled with twist and go machines but three decades ago almost every two wheeler in sight was a classic Vespa, Lambretta or Honda.

With such a rich resource of machines to draw upon, it’s particularly difficult to understand why most machines currently on the market in Vietnam are of such low quality.

When I started to delve more deeply into Vietnam’s classic scooter scene I expected to uncover organised crime connections or hard-faced con men at the very least but the truth is rather different. To understand how the ‘Nammer’ came into existence it’s also necessary to understand the country’ recent history.

1945-1954: The end of Colonialism and Acma

At the end of the Second World War, France assumed that its colonies would welcome it back with open arms. However the Vietnamese had very different ideas and in 1945 declared independence.

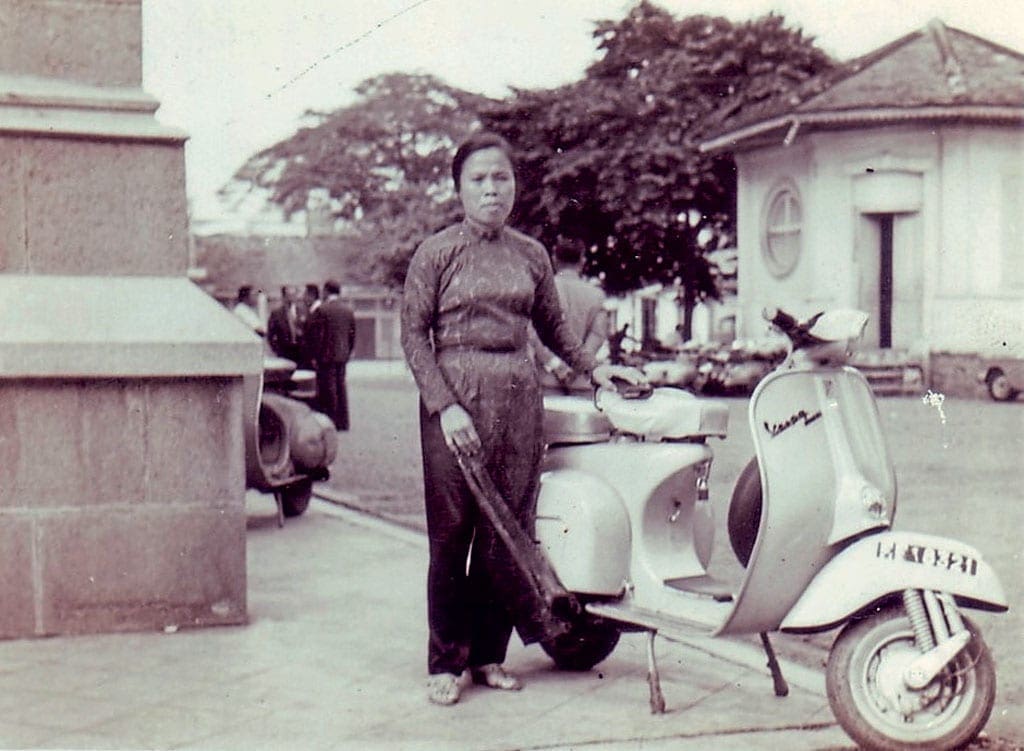

The ‘French War’ ended in defeat for the French who withdrew from the country in 1954. Behind them they left an unknown number of Acma-built Vespas that had been sold into the Vietnamese market.

1954-1968: Italian imports, Honda and a nation divided

Although it had gained independence, Vietnam was now a divided nation. As part of the peace settlement the North was governed by communists and the South by a ‘democratic’ government. This was the height of Cold War paranoia and the USA was terrified that communism would take over the world via the ‘back door’ of Asia.

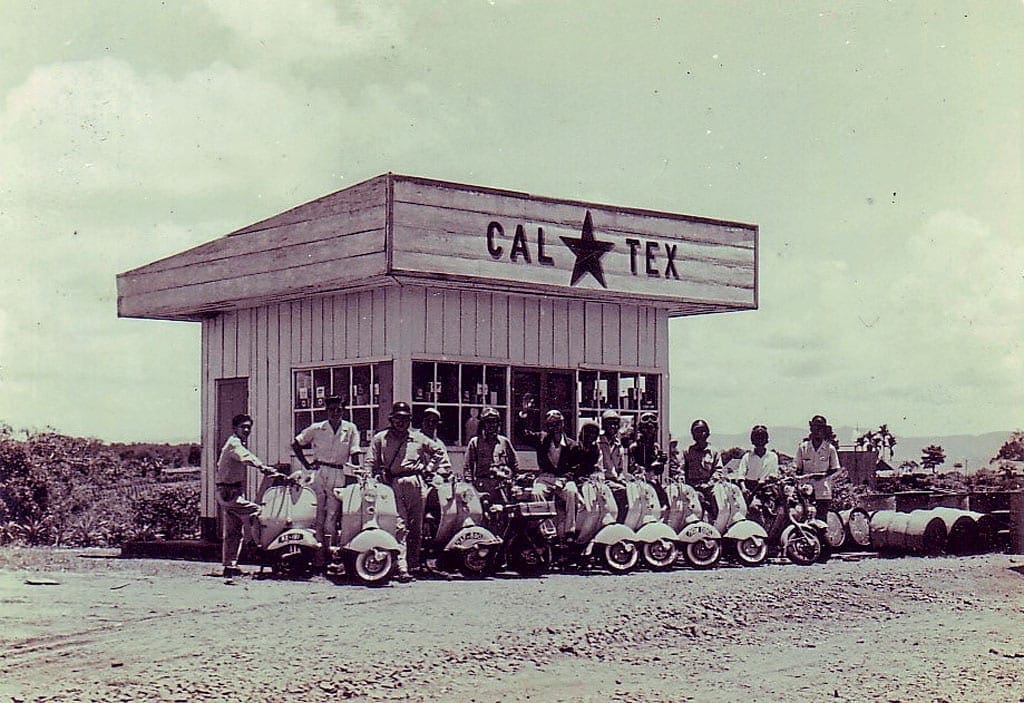

As a result the USA became increasingly entwined with a succession of corrupt and unpopular governments in the South. Despite the steadily escalating level of violence, political strife and civil unrest, the South still proved attractive to companies such as Piaggio and Innocenti who were joined by Honda in supplying two wheeled transport for the masses.

For Piaggio this included basic models such as the VBB and Sprint but also exotics such as the GS. Innocenti had entered the Vietnamese market with the LD and would eventually supply all models up to and including the SX. Unusually neither company secured dominance of the Vietnamese market.

1968-1975: A war of attrition on both fronts

In early 1968 Vietnamese communists mounted the Tet Offensive, marking the beginning of the end for South Vietnam’s government. As the military situation deteriorated so did the local economy. Anyone with money was taking it out of the country and they certainly weren’t upgrading to the latest scooter.

Consequently models such as the GP/DL and Rally are almost unknown in Vietnam and older Vietnamese scooterists are convinced that stocks of original spares had been exhausted well before the surrender in 1975. From this point on the only scooters to survive would be those with resourceful owners.

1975-1994: Communism and ‘hand built’ scooters

After reunification Vietnam closed its borders and turned towards the Soviet Union, from whom it received more than $3 billion in aid annually. It’s also important to note that although they had won ‘the American War’, Vietnam remained at odds with the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

Peace didn’t come to the country until 1989, by which time decades of conflict had taken its toll on the nation’s infrastructure, economy and population. With their more complex engineering, Lambrettas had quickly became a rare sight but the Vespa’s simplicity enabled repairs to be made with the most basic tools and materials.

Owners weren’t concerned with originality; all that mattered was that the family had transport. Surviving machines are often uniquely engineered and problems begin when parts made to original specification are used as they’re no longer compatible. Another factor in the longevity of these repairs is that although the typical Vietnamese scooter may have travelled over 250,000 miles it will rarely have exceeded 30mph.

The scooter’s always been used as a beast of burden and average speeds throughout the nation are low. Local repairs simply aren’t designed to cope with the demands of European roads.

The hardships faced by the population during this period of history can’t be overstated. Opening a Vietnamese engine to find shims made of drink cans and ill-fitting bearings shouldn’t come as a surprise – it’s to be expected.

1994-2005: Soviet collapse and the freedom to trade

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Vietnam began a series of reforms aimed at re-engaging with the West. By the mid 1990s, Vietnam had adopted a unique form of ‘market friendly’ socialism and for the first time in decades opened its borders to foreigners.

Among these visitors were motorcycle enthusiasts who were quick to notice the number of classic vehicles in daily use. Every Vietnamese aspired to Honda ownership and was eager to part with their old scooter to raise funds.

Over the next few years virtually every flagship model was snapped up by Westerners and soon there was barely a TV, SX or GS to be found. Broadly speaking, these were good examples of Italian scooters and many of them, now shorn of their provenance, grace collections across the world today.

2005-2010: Rise of the Internet and fraud

With the rise of the internet anyone, anywhere in the world, was suddenly able to value something they wanted to sell. Almost overnight scooter prices began to rise on the local market and shrewd vendors realised that a quick cosmetic overhaul would net them a better price. These were still ‘honest’ scooters but the supply of these machines quickly began to dry up.

Those feeding the international market resorted to increasingly desperate measures and by 2005 the quality of restorations had deteriorated considerably.

Scooters long since dismissed as being beyond repair or that had been cannibalised for parts were patched together with little concern for originality. This mongrel has given its owner nine years of trouble-free city riding. It’s been a hard life… or safety. It’s these machines that gave Vietnamese restorers a bad name, coining the derogatory term ‘Nammer’.

Surprisingly it’s not just foreigners that were conned. One notorious dealer offered to have a scooter rebuilt, resprayed and back on the road in three days. If that sounds unlikely it was about two and a half days longer than he needed to cut out the VIN plate, weld it into a reworked Taiwanese PX and blow over paint in that area.

More than one owner lost their cherished VBB in this fashion. The number of scooters subject to this kind of treatment is unknown but one dealer estimates that around 500 scooters a month were leaving Vietnam during this period.

2010-2018: Prosperity, appreciation and innovation

Over the past decade Vietnam has transformed itself from being a war torn, largely agricultural economy into an increasingly wealthy and educated nation. With this prosperity the Vietnamese are rediscovering their heritage and that includes the old family runabout.

Although many owners operate on a shoestring budget there’s an increasing number of enthusiasts who are prepared to pay for perfection. It’s companies such as Saigon Scooter Centre that are catering for this market and producing restorations that are, by any standards, world class.

Not content with preserving its heritage, Vietnam is also looking to the future. In common with many other countries Vietnam’s cities are plagued by pollution and electric cycles are becoming popular.

Unnoticed by most of the world is a locally developed e-scooter, soon to be launched as the ‘Buzz’. Although it’s classically styled, Buzz is way ahead of many rivals both in power and range. If it reaches its full potential this Vietnamese built scooter could steal a large slice of this growing market from under the noses of multinational motorcycle manufacturers.

It seems that the story of modern Vietnam and that of the humble motor scooter continue to be intertwined. There’s been an uphill struggle but it’s also easy to see a time in the near future when the term ‘Nammer’ will no longer be applied as a badge of shame.