Driven by the desire to distinguish their products from competitors, scooter dealers offered ‘special’ machines stimulate an air of exclusivity and individuality to cus attended rallies in the 1950s, something the emerging scene was quick to embrace as a ready-made style statement.

Allied with the newly devised and financially liberating hire purchase schemes, a prospective owner could in theory specify any level of accessories or embellishment to be grouped together in a number of easy instalments spreading the cost of purchase of the base machine and any additions over a number of years rather than in one lump sum.

Foremost in those early years was Andre Baldet with his two-toned Monas and Arc en Ciel Vespas. With distinctive sweeping accents of contrasting colour he set the tone for those who were to follow. Supreme Scooters in south London offered as enticement easily removed body parts in chromium plate rather than the standard body colour as part of the purchase price (presumably the base price was slightly loaded to offset the costs of stripping and chroming).

The dealership that brought all the elements of credit, extra colours, accessories and chrome together though was the now legendary Eddie Grimstead of East London. Noting a shift in ownership from middle class club orientated riders primarily utilising their scooters for commuting in the week and socialising at the weekend. The new breed of riders were younger more hedonistic custodians whose idea of club life was completely at odds with their predecessors and motivation was enjoyment with the scooter as a projection of their perceived persona. The scooter Mods had arrived.

Scooter Mods loved to be seen, their repurposed scooters, more often than not acquired from retiring club riders, once the pride of a concours line-up now taking their place parading up and down high streets and sea side promenades. Eager young owners would arrive outside scooter shops every weekend purchasing the latest accessories and exchanging body panels for chrome plated replacements. Too impatient to wait to get home, the Mods would add their new trophies to their scooters literally in the street outside the shop.

Watching this with wonderment the shop staff, whether it was Eddie himself or somebody else has been lost to time, hit on the idea of offering a scooter new or even a rehashed trade-in with bespoke paint schemes over chrome plate and modifications of the owner’s choice in a one price package available on the never-never with names to match, the Grimstead Imperial, Hurricane and Tornado legends were born. The Mods couldn’t get enough of his machines; in the capital they were the scooters to be seen on.

What, though, could a young Mod intent on high street immortality do if either they couldn’t raise a decent deposit or persuade parents to sign on the dotted line? Necessity is the mother of invention they say and as the Merton Parkas once sang “a man ain’t a man with a ticket in his hand, if you want to get a girl, you need wheels”.

The scooter obviously needed to be the starting point, second hand was one option, middle class professionals desperate not to be seen in the same light as the soon to be christened ‘Sawdust Caesars’ were off-loading their once cherished concours chariots, ideal starting points for an inventive young soul. Where once there was a tasteful array of accessories, every space would now receive some attention with Cavallino Rampante and Moon-Eye hot rod stickers filling the spaces other more expensive accessories couldn’t.

What though should be done about colours and chromework? Industrial practises and social conditions have changed in the intervening 50 years between now and the 1960s. Every back street housed a bogeit-and-scarper bodyshop that could – with varying degrees of sophistication – transform a scooter’s standard white flanks into rolling colourfully contrasting masterpieces within a few days. Failing that, touch up rattle cans available at motor factors such as Les Leston, could be employed with surprisingly professional-looking results.

If the owner lacked the necessary skills to master a vacuum cleaner paint gun or aerosol can, ever willing to oblige their young clientele’s wishes, scooter dealerships often offered re-finishing services with their own paint booths hastily pressed into service with stories of scooters being wheeled in, knibbed in, masked and painted within a day. A scooter would literally be transformed, including chrome exchanged in the space of a working day with the pavements outside resembling a youth club as youngsters waited patiently.

Chrome plating was an altogether different proposition though, needing the assistance of heavy industrial processes. Help was at hand however from car producing factories handily sited in most large cities. Scooter bodywork would be smuggled in through the back door finding itself being hung between door handles and bumpers destined to be fitted to Spitfires, Anglias, Moggies and Minis. It must have been obvious at seaside confrontations which scooters were owned by those with relatives working in the manufacturing heartlands of the Midlands, North West and East London as their scooters probably had chrome plating on anything that could be removed and smuggled through a manufacturing plant’s back door.

Enough then of historical conjecture and romantic rose-tinted theorising and on to this modern incarnation of what could have been half a century ago. Fuelled with anecdotes of how young peacocks found their way to high street scooter superstardom from the likes of Italian Tony in the Midlands and Don Hughes in West London, owner lain Wilkins embarked on a re-creation of a period specific machine that may have been the mount of an enterprising youngster who may not have had the outright finances to allow him to purchase a full-house dealer-built special but had enough street suss to build a scooter by his own means that would distinguish him outside the local Wimpey or coffee bar.

Reflecting the importance of the dealer network in the development of the scooter Mod look, their use as an unwritten no-man’s land for opposing manors, meeting place to plan raids to the coast and night clubs and impromptu youth clubs, lain chose to re-create a shop floor from the era complete with machines for sale and a mouthwatering display of accessories on the peg boards behind the counter.

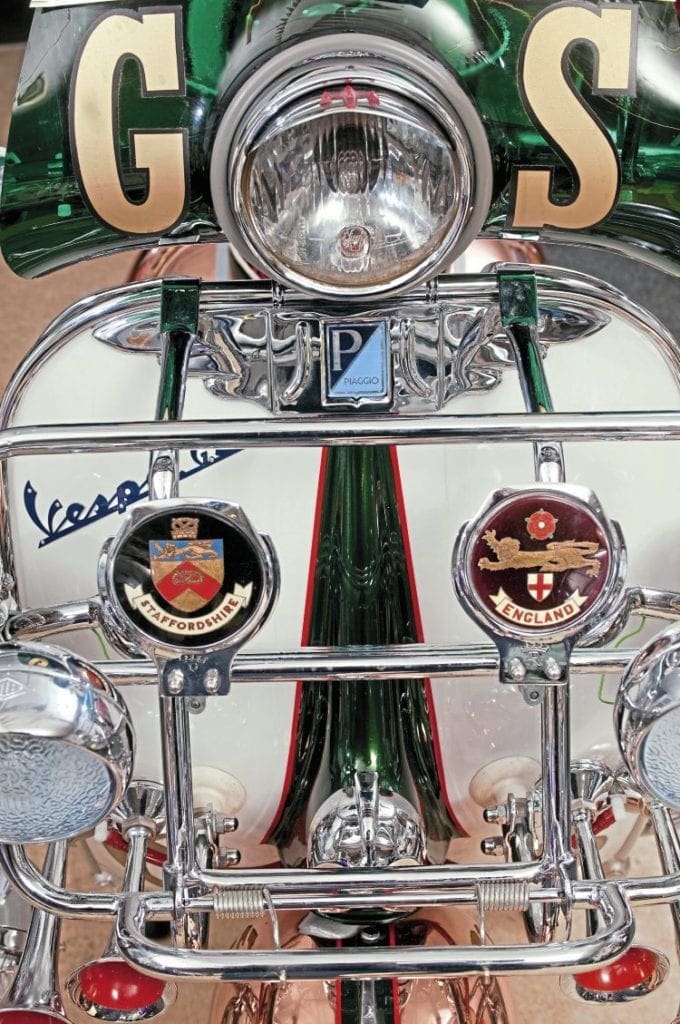

Having been told that Mods would ride down to London scooter dealers from the Midlands in order to exchange their panelwork for plated replacements and accessories from motor suppliers he sought out the same machine shops that spun Alpine Horn domes and platers that had supplied the likes of Astons and Grimstead and returned to the same Victorian workshops smelling of heavy chemicals and coated in decades of polishing dust to make his dreams a reality. Starting with a clubman inspired basis of minimal accessories and a striking colour scheme, lain took the route of having the panels, mudguard and horn tops copper plated rather than chromed, creating a striking contrast to the lustrous green and pinstriped red paint scheme expertly applied by Matt at I-Paint.

Staple early 1960s concours style accessories were added along with outlandishly rare items, frosted mottle effect lens Miller lamps rather than Raydyot items adorn the front carrier with curly bracket dynamo lights and Lucas rocket lamps further down the Ulma jug handlebars. A NOS Feridax screen was taken from its pristine box and decorated with Plastifilm cc stickers proclaiming the scooter’s original capacity. Tomaselli double legshield protectors complement the Vigano red gemmed rear crashbars themselves accessorised with an Ardour rear bar bracket below the Ulma number plate surround, layer upon layer of accessories added with Modernist discretion being the operative thought.

Following the riots of ’64 the look’ had been diluted from the bespoke suited style of the Italian look and Ivy League to a more casual-smart style with scooters following suit, performance though was still the name of the game. Beating all challengers and being known as the fastest rider in town still carried weight when ‘topping up’ on your rivals so it could be reasonably assumed that the same lire of thought could be applied to the scooters performance with the owner buying the GS pre-owned. Maybe coming upon it as a trade in and then retro fitting an engine from the most up to date machine offered, in this case, the SS180. Conveniently, this update of the piston ported Vespa engine shared the same general layout as the GS160 with the added advantage of improved performance.

Featuring a larger capacity, revised clutch and different gearbox the SS180 was faster off the mark and had slightly more torque than the previous model and improved reliability from the overhauled ignition system. Parts could be mixed and matched using an existing GS block or alternatively a complete engine unit could be installed from a written off SS. With a little fettling the wiring and ignition could be made to work; the only visible difference to give the game away being the extra bolt heads on the fan and maybe a different profile key in the ignition; a real street sleeper direct from the manufacturers. lain’s scooter has been further enhanced with a modern Vespatronic ignition in order to power the Alpine horns and Poli trumpets, the compressor for which is mounted beneath the tank.

The crowning glory though is the twin pipe Ulma exhaust with added GS150 tailpipe deflectors finished with lashings of chrome. The sound of which, popping as only a piston ported twin pipe Vespa can, is enough to transport you back to those heady post-riot days of the original scooter riding Mods.

MAN & MACHINE

Owner: Iain Wilkins

Occupation: Scooter entrepreneur.

Scooter model: 1964 Vespa GS 160, standard SS 180 engine with 12v Vespatronic conversion.

Paint: Colour over electroplating, standard GS grey/white, metallic green and red pinstriping by Matt at I-Paint.

Accessories fitted: Boxed NOS Feridax translucent flyscreen with pressed number plate and Plastifilm cc stickers, Decorette GS waterslides, ‘Up the Junction’ curved mirror stems with Raydyot threaded mirrors, Tomaselli double legshield protectors and Ardour centre connector, Ulma wing badge embellisher and horn cap, Ulma jug handle crash bars with Lucas rocket lamps and curly bracket dynamo cycle lamps. Ulma front carrier with Miller frosted mottled pattern lens, re-enamel badges, copper dome alpine horns, Vigano Jag lights, rear crashbars, Ardour rear mount. Ulma number plate surround with 3-in-1 rear carrier with backrest. Vigano wheel discs and spinners, Hi-Way faux fur Ocelot seat cover. Handle bar streamers, Metalplast grip and lever covers and mudflaps with Schwinn reflectors. 12v electric conversion powering a compressor for the horns operated from the handlebar horn button. Ulma twin pipe exhaust with flared GS 150 deflectors.

Iain would like to thank: Gary Dickinson for the use of his premises, for the photoshoot, Danny and Jon at Urban scooters, Matt for his time and patience painting the scooter.

Words & Photographs: Richie Lunt