Travelling Italian photographer Christian Giarrizzo discovered Sydney’s best scooter specialist once upon a time, and recalled the encounter in the pages of Scootering magazine…

I was a moody Lamborghini mechanic working in Australia during 2008 when I had a flash of inspiration, Destiny had brought me to the ‘biggest island of the world’ and I realised I was looking for a new life. It was one of those times when you ask yourself what is really important, what makes you really happy in life?

The Circular Quay of Sydney’s port was the theatre of my mind and my thoughts were passing back and forth just like the ferries under the big Harbour Bridge. In that moment I realised that what was driving me to explore was the Fujica analogue camera, always around my neck. I hadn’t understood that photography was such a big part of my life till that moment in Sydney.

The next day I resigned from the Lamborghini shop where I worked. “What are you gonna do now mate?” the owners asked me. “I think I’ll take my Vespa, build up a photography website and became a reporter-on-wheels,” I said. I will never forget the astonished looks on the faces of my Aussie friends but in fact, from that point on, I never stopped.

I rode a PX150 for 10,000km in the outback and when back in Italy I christened my Vespa (the only thing I had left before leaving for good) ‘La Negra’ (the Black) and continued on my travels. Since then I have wandered like a gypsy, looking for stories, using my camera and my notes, and recently I reached Australia again.

This is the story of an old friend of mine who is devoting his entire life to Italian vintage scooters. In some way our paths are linked; we were both Italian immigrants in Australia, making our own way in the ‘new world’ down under.

I get up at 6am in the morning, the slumber of the night still draped over Sydney like a blanket of silence. The black PX200 rented from a friend makes its way through the wakening city, while bridges and roads of the eastern bound are just beginning to echo to the sounds of weary early morning commuters.

Leichhardt, known as the ‘Little Italy’ of New South Wales, Australia, is a suburb of Sydney. Italian immigrants settled here after the end of the Second World War. At weekends during the 1970s the main square used to be overcrowded by compatriots who had saved up their pennies to call home; the receivers of the two telephones allowed for international calls used to stay hot well into the night, filled with the eager chatter of hopes, dreams and confessions.

The same square was a social meeting-point too and a black market business place. You could pick up cigars, spirits, clothes or the latest job bulletin. I cross the Anzac Bridge, pulling on the left row directed to Balmain Road, the Moore Street traffic light and the Hawthorne Canal delineate the borders of the Australian Italy. I stop at the Parramatta Road corner for a break as the owner of a nearby pub is tiding the tables outside his property. It is a day of early autumn in Australia and he is already enveloped in his warm jacket to keep off the morning breeze. “Is this your Vespa? Do you where it comes from?” he asks. “Yep, I know a few things about it,” I smile.

After five minutes of pleasantries, Paolo switches his tempo quickly and starts to speak Italian: “Cosa fai in giro a quest’ora? T sei perso? (What are you doing here in the morning? Have you lost the way?) “No sir,” I reply, “I would like to interview Tony, the mechanic, I’ve been told he is the best Vespa specialist in whole Sydney.” Paolo laughs profusely. “He is not only the best, but also crazy enough to service only Vespa, Lambretta and Italian motorcycles!

“I saw him pushing away a Honda customer once, cursing in Sicilian dialect. He is a good man though, don’t worry”. A familiar sound reaches my ears, it sounds like an early ’50 Vespa, and I am right because this is how I meet Antonio.

Puffed up on his ‘Bellissima’ (150cc Vespa ‘Struzzo’), proud as a teenager, he waits for the traffic light hanging a yellow bag on his left hand. As if by magic and just like in some little villages in Italy where everybody is updated on everything, he knows already my journalistic intention, beckoning me to his shop nearby. Just before 7am my favourite baker cooks three ‘cornetti’ for me. “There is no hope of seeing my shop open if I can’t buy them,” he says. I try to rattle off a few questions but he stops me with a single sentence: “Prima it caffe.” (Coffee first).

We settle in a mezzanine that dominates the entire workshop: a wooden table, a kitchen and an office are everything Tony needs to manage his business. When we are inside he asks me to help, and while I prepare the coffee using the typical Italian ‘moka’ my host brings out the jam from the fridge, cutting slices of warm bread. For a second I am a child again. My grandmother in Sicily used to prepare breakfast in the same way.

“Many of my customers pass by here just to drink good coffee and enjoy the company. I don’t mind it, nor want money to prepare it. If someone comes here to smell the scent of Italy, we can build up a friendship”.

Tony is 74 years old. He arrived in Sydney in June 1960 after a month-long sea journey in a passenger ship. “At the time I was shattered and worried, doubts were nibbling my conscience,” he tells me. “I had to use all my savings to pay for the trip and I was only 19. The journey was anything but comfortable, despite what the brochures had said. I alternated thoughts and afterthoughts with the same constancy that the choppy sea battered against the ship’s hull.

“Was leaving my native region the right thing to do?” Antonio stops for a while, looking beyond the office window. Even today I find hard to imagine what it would be like, leaving Italy in the 60s, waving to all my loved ones and setting sail for an unknown and far distant land. I’ll never forget the slowness of the travel, day by day fighting the big blue.”

A smile appears on my face, thinking about the new ‘slow tourism’ which encourages us to take our time to visit, to not being in a hurry. Tony’s eyes looked out from the deck of a storm-tossed boat at landscapes as the Suez Canal, the equator which “choked the breath from our lungs with its tremendous heat,” the Indian coast of Colombo and Australia at last. “It was so big. Do you know, son, that coast to coast by plane it takes six hours? Try to imagine by ship. I remember the excitement of seeing her shape from afar after so many days of anxiety.”

The workshop compressor starts up and brings us back to the present with a start. Tony is dressed like a real mechanic, wearing a blue jacket with discoloured writing across his back which reads ‘Vespa Servizio’. Downstairs in the workshop, a 55-year-old table shows the scars of long and dutiful service, the metal surface is glossy and well used to the rituals of pistons, clutches and motors. I wonder how many motors have been brought into a new life in this little corner of Italy.

“During the cold mornings, in winter, I lock myself in the office, tune the radio broadcast to my favourite station and when my old bones are sufficiently warm, I make my way towards the working area.”

Antonio last job is a full restoration of a 1965 150cc Vespa. He moves slowly in his place but every gesture is measured and precise. Just like a sculpture, the engine on the bench starts to take shape. Tony’s hands alternate between strong, deliberate movements and thoughtful pauses. Sometimes he lubricates his middle finger using a film of oil from a red bottle, then slides it along the perimeters of the crankcase in a sort of gentle caressing motion.

“When I arrived in Sydney I did not know a word of English, it was so hard. My first job was at a company specialised in cleaning marble. It was only a two-day adventure, because as soon as my cousin told me there was a motorcycle garage looking for specialists, I gave them my resignation. My excitement was so much, that I didn’t even return to take my wages.” He pauses, looking me straight in the eyes. At 15, in Sicily, I got up at 5:30am to catch the bus off to work. I used to arrive at least one hour before.” He blinks at me. “It was purely so I could drop off the cars/bikes from the boxes. Then I specialised in Vespas and Lambrettas, I loved those little gems and as you can see I still do.”

We are interrupted by a phone call from his wife. Tony, despite having undergone two heart-bypass operations still wants to work. His wife looks after him and rings at fixed times to see if everything is okay.

“I’ll quit when I’m not be able to crack my ‘Bellissima’,” he snorts.

I ask him which one is the best, Vespa or Lambretta? A hint of malice gleams in his eyes. “If you are a professional pickpocket Lambretta is better! It has the engine in the centre and you can lean more in the corners. Nobody can take you!

“Vespa on the other hand is style and design too. Who do you like the most ¬your mum or your dad?” he teases me. “It’s the same with your question, boy.”

He works alone in the shop that he has earned by the sweat of the brow. Occasionally some friends help and in return he teaches them how to take care of the oldest of models. “Spare parts are a problem here in Australia. With luck, you get them in a few months and often when they arrive are wrong. There is too much plastic on the internet nowadays. The last week I spent three hours tuning a PX gearbox bracket, it is a five minutes job using the genuine part.”

It’s lunch time and we sit down together. Pasta with meat sauce (spaghetti al ragu). Antonio checks his workshop while our forks are clinking.

“I built everything you see by myself, when I was working at the BMW dealer, I used to finish at 5pm, had some fast food and at 7pm I met with another scooter-dealer, we sold what I used to repair within four hours work, and this was every evening of the week.” I get up from the table, looking at those walls. This is what hard work and passion can bring you. If you remain stranded with a Vespa in Sydney or you want to sample an Italian coffee, M A Motor Garage is the place.

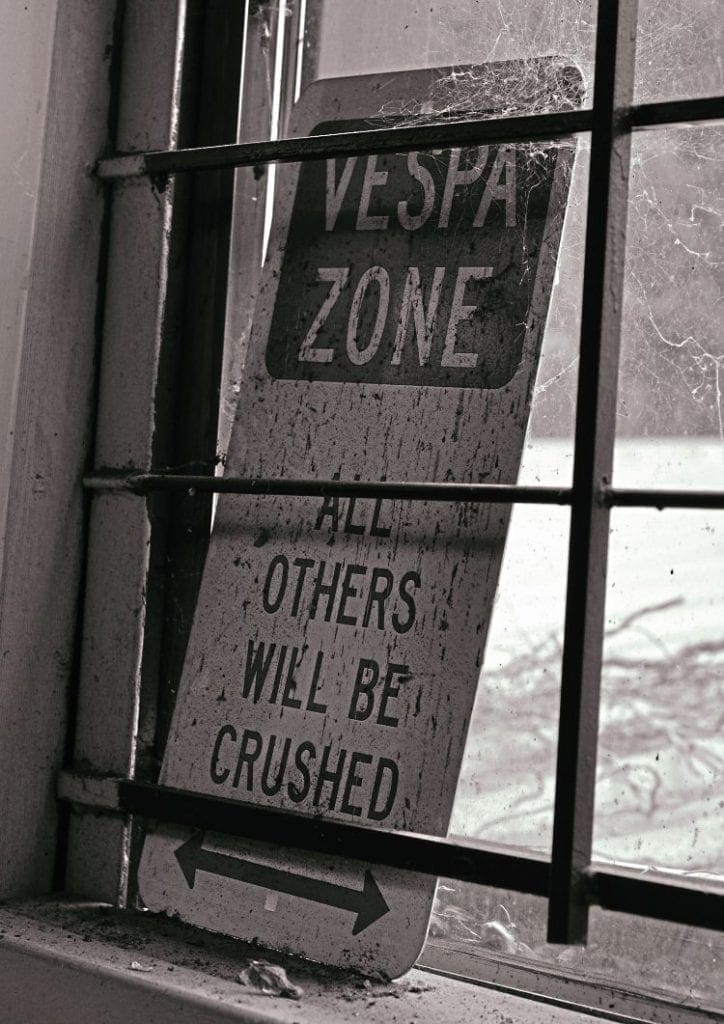

Only Italian scooters though. The sign is clear on what could happen to others.

Words and photography: Christian Giarrizzo