Thought to have been lost forever, one of the most famous Lambrettas resurfaced in 2005. It was in an appalling state and the challenge now was to resurrect it…

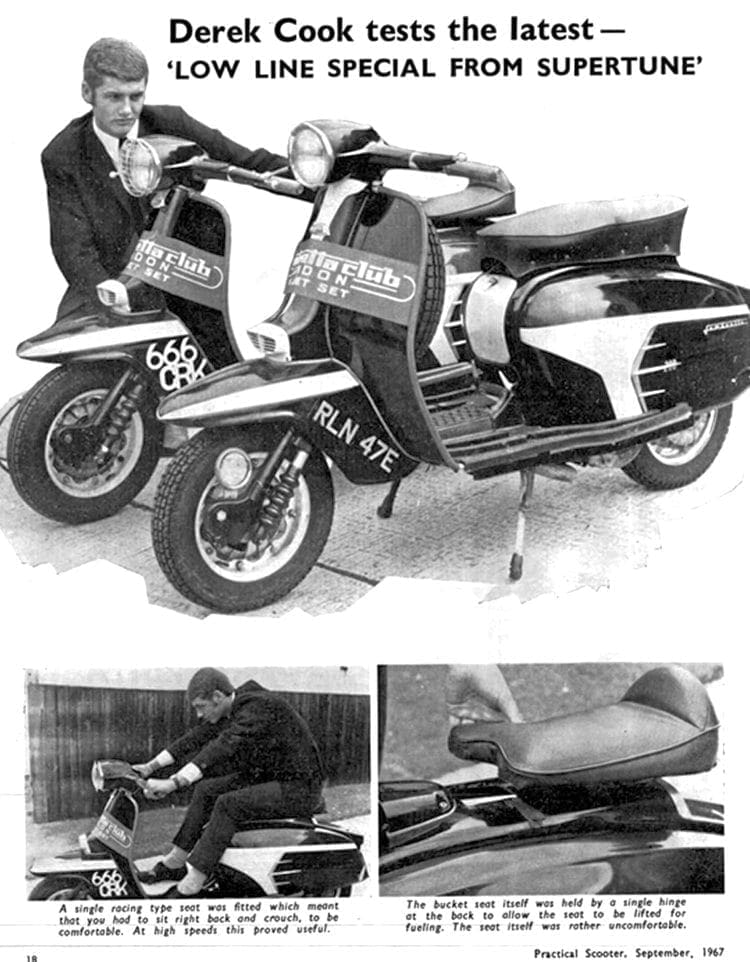

In 1967 a three-page article in the short-lived publication Practical Scooter and Moped featured one of the first ever racing Lambrettas in Britain. Built by Supertune, the Croydon-based shop run by Malcolm Clarkson, it was innovative and way ahead of its time. In an era when the only other purpose-built machine by a dealer that bore any resemblance was that of the Arthur Francis ‘S Type’ it was uniqueness personified. Not only was it tuned but for the first time, the chassis considerably altered by lowering the front end. Labelled the Supertune Low Line Special, it was pioneering and paved the way for Lambretta tuning and modification as we know it today.

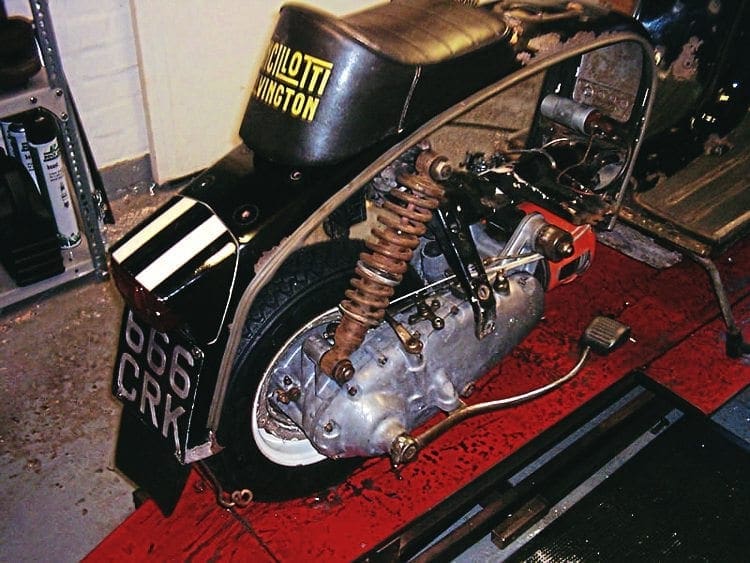

Having spent several years being raced at circuits round the country, it disappeared altogether sometime in the mid-1970s. By chance, it was unearthed by current owner Richard Soloman during 2005. Having spent the last three decades locked away in an attic in London one of the most legendary and iconic Lambrettas ever built was once again ready to see the light of day. There was a major problem though, in that it had suffered heavily from neglect.

Despite being kept in dry conditions for many years, prior to that it had lain outside for some considerable time exposed to the elements of the British climate, apparently under a tree. Not only did the bodywork suffer but to complicate matters further the whole thing had been stripped down with most of the contents stored in old boxes and biscuit tins. Luckily when Richard discovered it everything from the machine was still there so potentially there was a chance of it being put back together. The challenge now was how to go about doing so.

Jigsaw puzzle

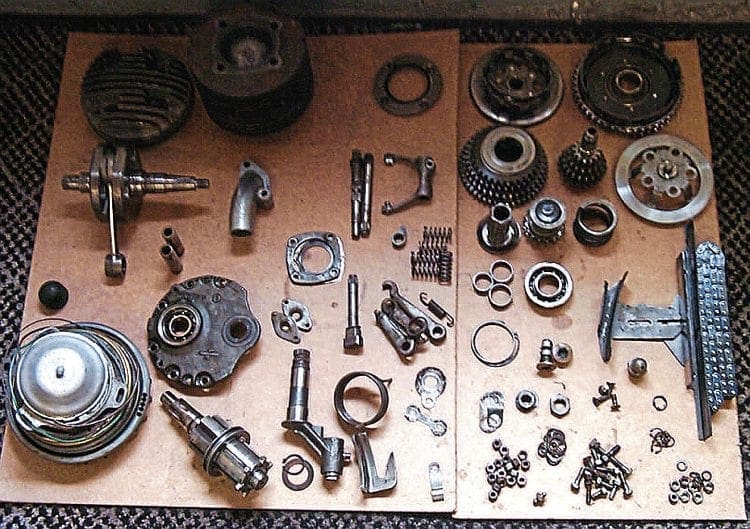

The first procedure was to lay everything out on the floor to see if there was anything missing. If anything was then a suitable replacement would be needed but upon first inspection, the majority of it seemed to be present, certainly in terms of the bodywork. The engine had been removed as one piece so for the meantime could be put to one side. What now needed to be examined were the many smaller parts and more importantly the majority of the fixings that remained. A wide array of period biscuit tins and small boxes seem to house virtually every nut, screw, and bolt that had once held this glorious machine together.

Even the inner and outer cables that were originally fitted were intact and indicated that the complete workings were carefully preserved when it was pulled apart all those years ago. Realising almost 100% of the original machine was present left Richard with the dilemma of which route to take when putting it back together. Some of the paintwork was, shall we say, nonexistent due to areas of rust and what was still intact, covered in years of dirt even though that had helped protect it to a certain extent. The choice was simple — to clean up what already existed or do a full restoration. On a normal find, the second choice would have been the obvious route to take but this was no normal Lambretta. It was steeped in history and a lot of it recorded in time for all to see. The process of restoration would mean that would be gone. As the saying goes ‘it’s only original once’. Without any hesitation, thankfully, Richard decided it must be preserved — meaning it would be cleaned up and kept as the original machine. It was never going to be pristine but with enough hard work and determination, those put in charge of the renovation were confident of a good result.

From the ground upwards

Once it had been separated into groups of components, the cleanup could begin in earnest. Rather than just clean up a part and fit it, the decision was made to clean everything ready to rebuild the scooter all in one go. That way any part that was missing or needed repairing could be sorted beforehand, preventing delays in the rebuilding process. Before any of this took place the frame itself was carefully inspected for damage.

The frame is what everything is bolted to and if that wasn’t good enough to use or needed an important repair it was pointless doing the rest. Thankfully it had survived fairly intact considering that this Lambretta had spent the majority of its life on the race track. It had gone through several owners, all of whom can vividly remember falling off it at one time or another. Looking at the frame from the front and keeping a level eye on the fork stem there was the odd twist on the struts and the top shell but the main tube remained fairly in line. The majority of Lambretta racing frames are in a similar condition if not worse, so this was good news. With this in mind, the frame was cleaned and readied for when the rest of the components were available to fit.

The first major cleaning job was that of the body panels and anything with paint on it. Though some parts had areas of rust, the majority of the paint had remained fairly intact. Armed with industrial quantities of T-Cut and a lorry load of cleaning rags the hard-baked dirt and grime that engulfed every square inch of each part could be attacked. If anything it helped protect what was underneath and it soon became clear that it was going to look better than was originally thought. The areas of rust were cleaned up and when finished with a protective layer of Anchor wax to prevent it from coming back. Luckily with the majority of the paintwork being black, the areas of rust don’t show up as much and once sealed were not that noticeable.

The cleaning process was laborious and hard work on the hands, with hours and hours spent on each part; not to mention a number of clothes that had to be thrown away because they were beyond washing. Even so, as each piece was finished of it was almost like they had new life breathed into them. To think that this paint had been sprayed on some 40 years earlier and now saw the day of light once again. It was almost like the renovation of an 18th century painting revealing its past in great detail.

With the paintwork out of the way, attention could switch to all the fixings which would be the real mind-numbing part of the job. Though most of it was in good condition each part would either need wire brushing or the use of wire wool to clean it up. A total of three wire brushes were used and worn out and a full pack of wire wool. Using the wire wool with a mix of white spirit (the best chemical to use in a renovation without damaging anything) bit by bit each nut and bolt was carefully catalogued ready to use. After almost a month of work and long sessions of cleaning, good progress was now being made even though there was still a long way to go.

Motoring along

The engine condition had many good points about it and most importantly it still turned over; usually after this long they are seized solid. The original engine, which was 235cc, was long gone and apparently had blown up at a race meeting in around 1968. It had subsequently been fitted with a Li 150 engine and TV 175 top end and as this was what was last used in it would remain so. There seemed no point trying to build a new engine reminiscent of what had first been put in it. Several things had changed on the machine as a whole which was a natural progression over its used lifetime so it would remain that way.

Not only was the engine free from seizure, it was free from any rust inside and the majority of components were perfect. The oil seals and gaskets would need changing as too would the clutch plates and the odd bearing here and there; there was no way around that. Everything else though would be retained, which was quite unbelievable considering it was a race engine. The top end was from of a TV 175 and the barrel had been considerably ported by JJM who had their own scooter race team in the early 1970s. JJM stood for Alan and Dave Jupp and Paul Marshall, who were having good success on the track at that time. Dave Jupp would be the tuner of the barrel while Paul Marshall would be the chief mechanic. Alan Jupp was the rider but it is known that several people raced the machine during that period. The carburettor was an Italian 22mm Dellorto from a GP and the exhaust a big bore but it’s uncertain who made it. From the details known the engine was quite competitive and was a fitting piece for a Lambretta of this pedigree.

When fully stripped the casing revealed no damage whatsoever and once cleaned was rebuilt using almost all of the original components. Though the piston rings were worn some replacements were found and the barrel and piston still had good compression. There was no reason to doubt that when it was fired up the engine would run perfectly.

Coming back together

Finally, after all the long hours of sorting hundreds of components out, all the scrubbing and scouring clean, each individual item of 666 CR K or ‘the bike of the devil’ as it’s more commonly known was ready to be put back together. It soon became apparent that there was a problem that would prevent it from ever going back on the road, certainly from a legal point. When the front end was originally lowered by 3.5in the part of the fork tube that housed the steering stop was removed.

This meant that the forks could turn all the way round which is not only dangerous but a fail on an MOT. Back when this conversion was done in the 1960s things may not have been so strict but in saying that it should have been done back then from a safety aspect. That was immaterial to the situation now facing Richard; what was needed was a solution that didn’t involve welding to the frame and destroying the paintwork. The solution, in the end, was simple enough by putting two stops in the way of high tensile bolts either side of where they needed to be on the tube. All that was required were two small holes drilled and tapped to 6mm where a short bolt could be screwed in each side. These would protrude into the fork tube enough to act as a stop against the opposing one on the fork stem but not enough to foul the stem.

With steering issues out of the way, the rebuild could commence and seeing it come back together after all these years later was a sight to behold for anyone who is an enthusiast of the Lambretta. There were no major problems from then on and if anything it was pretty straightforward, reuniting each component one by one. The only part that was unsalvageable was the seat due to a combination of race damage and the outside elements doing their best to ravage it. Richard now had to weigh up his options. This Lambretta had always had a single seat fitted and any replacement would have to go along similar lines. By chance, an original condition Ancillotti Elvington seat became available, not only similar in shape to the original but also aged, making it blend in well. This was the final piece of the jigsaw and now meant everything was in place to sign the project off.

With a fresh tank of fuel the engine was turned over and after a few kicks, it burst into life. More than 30 years after it had turned a wheel the Supertune Low Line Special was ready to venture back out on the roads once again. This was a pure racing Lambretta and though its performance was nowhere near that of today’s modern machines it still gave a good account of itself. The bashed and bruised chassis, slightly out of line, handled well enough even at high speed. That was of little importance though; what did matter was that this iconic scooter had been resurrected and would be preserved for the future.

Ten years after its resurrection 666 CRK still gets used on regular occasions by Richard which can only be a good thing. Rather than dust it off every now and then as a museum piece it can often be seen at ride outs and rallies for anyone to look at and appreciate. Time has taken its toll on some of the components, certainly in the engine, so these have needed replacing but does it matter? I don’t think so. What’s important is that a major piece of Lambretta history has been preserved and hasn’t been locked away.

Footnote

666 CRK spent just over 10 years on the road from 1964 to 1975 before its long hibernation. Though much of its history during that period has now been unearthed, Richard is keen to find anything else out about it during that time. If anyone has any information or photographs of it during these years please contact us here at the magazine and we will pass the information on to Richard.

Stu Owen