Words & Photographs: Christian Giarrizzo

The Lambretta Luna line celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2018 and our own Italian stallion Christian Giarrizzo met a man for whom the Italian market Lui is an object of fascination.

The Italian word ‘lui’ translates as ‘he’ in English, but there is nothing masculine about the type of machine I’ve come to see. I see it rather as the travelling companion of a woman – blonde and slim, who gets up early to find the best deals at the fruit and vegetable market, perhaps carrying away her purchases in a distinctly feminine wicker basket attached to the handlebars.

In days gone by, the Lui scooter was at the epicentre of a seismic commercial struggle between those two giants of Italian industry, Innocenti and Piaggio, with neither sparing any expense in showcasing their wares to the public through rival advertising campaigns. The battle was played out across the covers of magazines, on billboards and on colourful posters clinging to street furniture.

Innocenti spared no puns when it came to pushing its radically-styled new machine. ‘Lui per tutti… tutti per Lui’ was the catchy slogan used, which loosely translated as ‘All for him… him for everyone’. Innocenti wanted everyone to have a Lui, but unfortunately not everyone was enamoured with the Lui’s bold looks and bright colours. Piaggio eventually won that battle and the Lui disappeared into the abyss of history.

This strange machine – now almost completely extinct – has always held a curious fascination for me. A few months ago I decided to follow the advice of celebrated war photographer Robert Capa, who said: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” I needed to get close to a Lui.

The ideal opportunity presents itself when Lambretta expert Bruno Pisaniello, of Scooter Italiano, rings me to tell me about a new exhibition he has set up, dedicated to the Lui. Needless to say, I am eager to find out more. And more there certainly is.

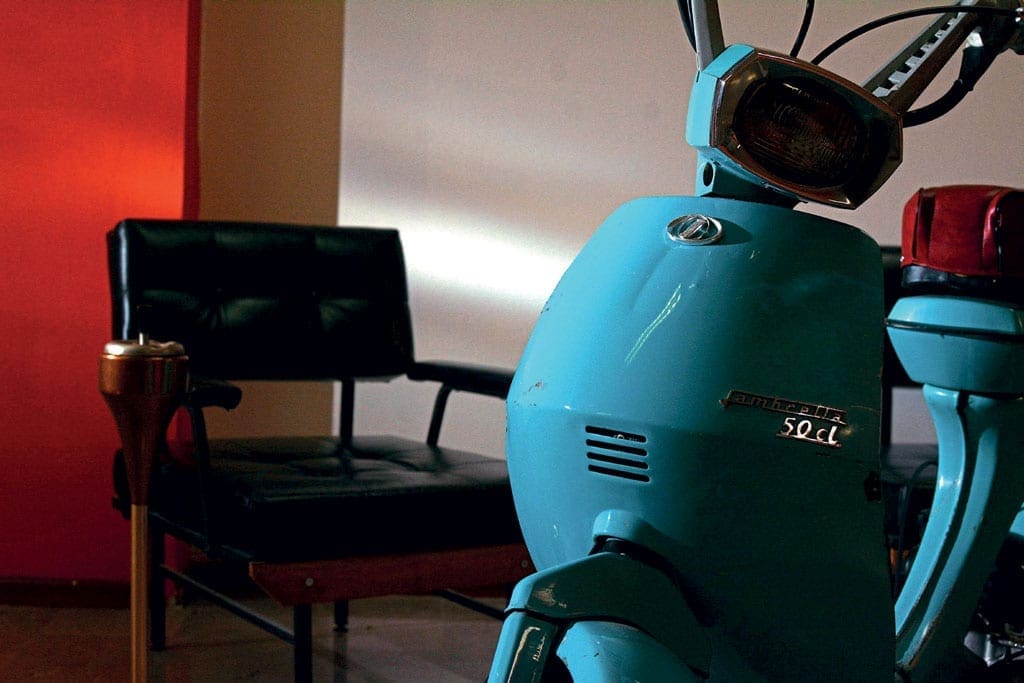

“We’ve set it up like the ’70s,” Bruno tells me excitedly. “Everything’s just like it was back then – furniture, lights, reception in full psychedelic style. You’ll love it.” I found myself very much hoping that I would.

I grab my camera gear and notepad, hop aboard my Vespa, and make my way over to the converted hotel in Via Pordenone in San Quirino, Italy, that is Scooter Italiano’s headquarters. It isn’t the smoothest of journeys, with a lorry doing 30kph over the limit taking me by surprise.

The roadside ditch beckons, but I’m not going to be so easily deterred from my rendezvous with Lui. Pulling into Via Pordenone, I find familiar colourful posters awaiting me and some familiar Lambretta models parked outside, too.

Bruno is clearly a busy guy. I can hear his phone ringing off the hook as I walk across the long iron bridge leading to his workshop. Stepping inside, I see no sign of the usual workshop accessories – no lifts, no benches, no tools. Bruno notes my questioning look and treats me to a broad grin. He indicates a switch on the wall which, when activated, reveals the real workshop hidden out of sight beyond.

“Did you cross yourself when you came through the door?” he asks me. I shake my head and ask why. “Because here you are on sacred ground, my friend. These walls have heard the sermons of the parish priest for years. That spot,” he says, indicating a nondescript part of the reception area, “was where the high altar stood. Where we are talking now was where they had the confessional. What better place to lay my beloved Lambretta eh?”

I realise for the first time that we are standing in what was once a church. Holy Lambrettas. As I gaze around in bewilderment, it occurs to me that the place is worth an article in its own right, but I’ve got to stay focused. I’m not here for worship. Or maybe I am. There are more than a few icons here, as I soon discover.

Bruno’s exhibition opens up in front of me with all its vintage divans, electric blue carpets and other paraphernalia of the past, and Luis – a whole host of them. I’m abruptly brought back to the present by the sound of Bruno’s smartphone. He casts a desultory eye over the screen before shutting it down and stuffing it back into his pocket.

We sit amid the scooters and posters from that long-lost advertising campaign, and I ask Bruno where all this came from. “Everything started with the EuroLambretta rally held in Adria. My friends and I were dealing with the organisational side, and I was also engaged in the role of DJ.” This tickles me somewhat and I ask him flippantly what song he’d have on his headphones while climbing into the saddle of a Lui.

“Good question. Maybe a piece of soul funk from the end of the flippantly flippantly ’60s, but I’m a Mod so I think I would like to play Magic Bus by The Who. Anyway, during EuroLambretta I remember seeing a couple of travellers who’d rolled up on Luis – a father and son. It made me smile. It occurred to me that 2018 is the Lui’s 50th anniversary, as well as being Lambretta’s 70th, so I decided to go against the prevailing tide of nostalgia and organise an exhibition just for the Lui.

“It’s a bit of a black sheep with an unhappy story, which tends to intrigue people. Despite its unusual shape, it tends to attract a lot of interest whenever you see one. I have been particularly surprised by the amount of sympathy it gets from young people. Maybe it’s because they do not take it seriously.” He shrugs and stops for a moment, before resuming.

“With the Lui you have to take the necessary time yourself and give the scooter the necessary time. When you’ve given yourself a chance to understand it, and you’ve given the scooter a chance to show you all of its details, its curves and its features, then you can see the whole picture. These things take time.”

I can perfectly understand what he’s telling me. It’s the same when you’re taking a photograph. Some things just can’t be rushed, and appreciating true beauty is one of them. He goes on: “I just couldn’t bring myself to gather a collection that was just documents and a few posters. I had to provide a setting that would be as sympathetic to the Lui as possible.” I look around and see that the Lui specimens gathered here are set like precious stones in bedrock. Bravo, Bruno.

“My brother is a passionate window-dresser and together we have recreated the exploded Lui hanging in space, suggestive of the machine’s air of sadness and romance. It has a double meaning, too, since the scooter never did explode in sales terms.” He giggles nervously. Perhaps he thinks I believe that he’s gone a little too far with all this.

I’m still on the same page as him, though. He’s right, because the scooter came out in the ’70s, but the ’70s weren’t very kind to the scooter. I find myself wondering why exactly it was that this paragon of innovation and cutting-edge design failed to take off.

Bruno has his own answer: “It was too much, too far from the reality of the life that most people found themselves living at that time. It was the dawn of the space age, but most people didn’t feel that in their day-to-day lives. The scooter was too complicated, just too much. I’ve ridden around on it and even I can see what happened. It’s too hard to work on.

“You break a cable and you end up selling the scooter out of desperation. My trips have hurt this too-delicate piece of technology. I hit and damaged a piece of front mudguard and a piece of the frame. The tail-light has to be unscrewed, and every time you do it you spend ages just disassembling it. It is complicated in its simplicity, if that makes any sense.

“If you want to repair the legshield, you have to move the fork. It’s depressing, frankly. I can imagine that Innocenti’s technicians found it depressing, too. The company just tried to do too much that was new. Tt was a jump into the unknown.”

I ask Bruno how he’s found the Lui riding experience. “Flat out on level ground, the speedo always stops at 40mph. You can imagine what happens when you reach mountains.” He pauses, and it’s silent as the grave in his exhibition space, but then he smiles again and says: “If you forget to fill the fuel tank, the Lui is incredibly frugal. I estimated more than 34km per litre, which is about 80 miles per gallon. So it could have been a real commuter machine if anyone had wanted it to be.

“At the time, so much effort was made to sell it. They even entered it in a ‘seigiorni’ race up in Germany, which ended badly with both vehicles withdrawn on the second day. Lui just wasn’t understood by anyone.

“It was the focus of advertising at national level in Italy with celebrity endorsements from important actors, popular musical groups, and some truly formidable photographers at the top of their game. One of the advertising campaigns they conducted, produced in Sardinia, was original to the point where it is still being studied as part of university courses in design and photography here in Italy. Despite all this, there was nothing anyone could do to save it. Then again, even Picasso’s works did not receive any consideration at first.”

I take a last turn in the exhibition hall of the former hotel/church and I linger on a yellow Lui with a four-leaf clover imprinted on the bodywork. Bruno’s not one to miss an opportunity: “This example was kept at the Innocenti offices, they used it inside their walls, so they branded it with the four leaves the hope of good luck. It didn’t work this time though.”

Just before I leave Bruno, the image of the blonde and her shopping basket reappears in my mind. Despite its name, I still do not see the vigour and masculinity of Lui or ‘he’. I don’t feel as though I understand this iconic scooter yet. Perhaps I just need to give it a little more time.