It’s not easy to cope when a loved one is at death’s door… especially if it’s your scooter. Our man in Italy, Christian Giarizzo, opts for a radical intervention but will the scooter he knows and loves survive the procedure?

This scooter is deceased

I was locked in my garage in Udine, northern Italy, looking at my 150cc VBB Vespa and there were tears in my eyes — I could hardly tell if the hunk of machinery sprawled across my workbench was lying on a hospital bed or a slab at the morgue. After eight years of sterling service, and a total of almost 125,053km with me sitting proudly on board, I’d decided it was time for my companion to undergo a major surgical procedure. It was going to be risky, and it made me feel like sobbing, but it had to happen if we were going to have any sort of future together.

Remarkably, in spite of everything the engine was still 100% functional and even more astonishingly it was running on a genuine 1989 condenser. During our many happy years on the road I’d changed the points three times — the last time was in pitch darkness in the middle of a Sicilian dirt road, with only a prehistoric Nokia phone gripped beneath my teeth to shed any light on the subject.

Forgive me if I digress — so many memories are wrapped up in the oily chunk of metal that is my scooter. We climbed the central Apennine mountains five times and followed all the main peaks from northern Italy all the way down to Mount Etna in Sicily. We explored sand roads in the Balkans, travelled to Montenegro and even rambled down dusty tracks in the Australian outback. We met dozens of wonderful, humble people together; people who had good life-lessons to teach — from blue collar workers to politicians. The good times couldn’t last forever though, there’s always a price to be paid in the end and a realization dawned on me in December 2016 – to paraphrase the Italian fashion designer Valentino: “Much better to leave the party when it is still crowded than to see yourself desperate and alone.”

Nailed to the perch

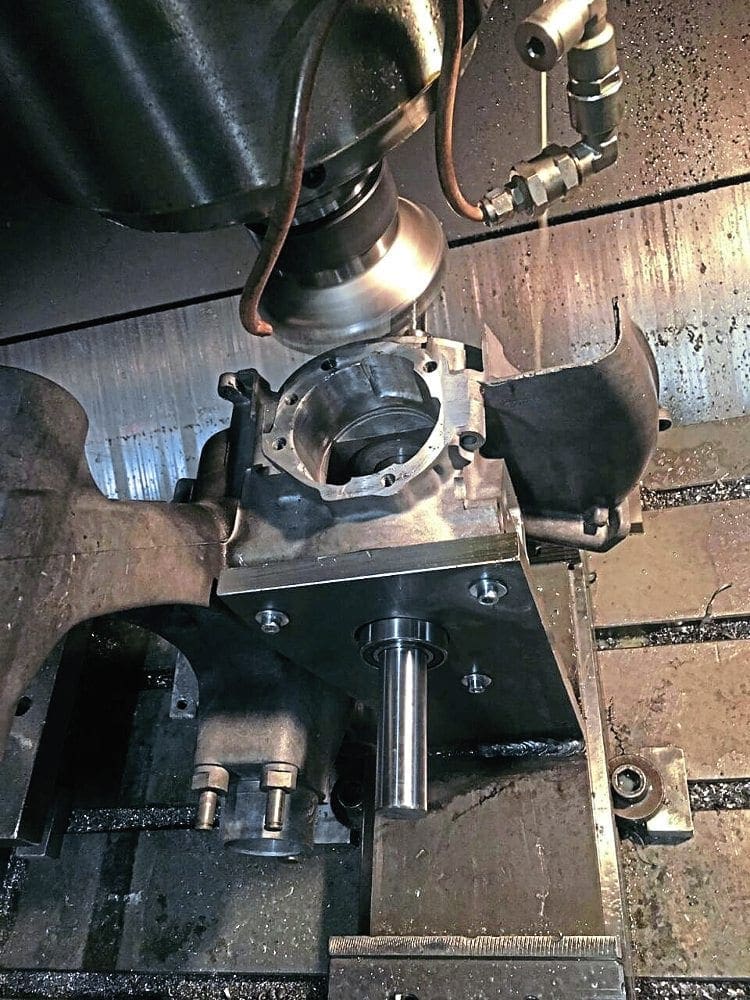

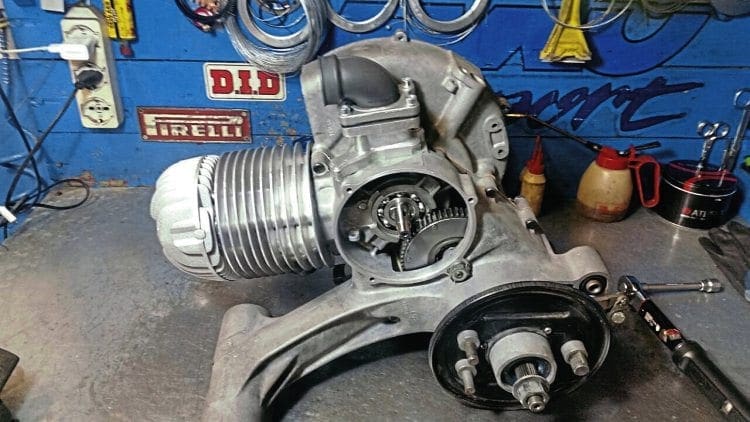

So my scooter’s engine was still working 100%… and if you visited my home you would see it looking intact and dignified, but it was just a front. It was now developing less than five horsepower. It was tired and I knew what I had to do but I couldn’t face it. For the first time in my life I decided to leave the job of building a new engine to somebody else. This was a huge step for me — I was so used to caring for this machine, checking it, mending it, giving it the very best of everything that I can. It took me a month to get there but in the end I picked up the phone and, voice wavering, explained the situation to Cristian Cernettig, the guy who built the furious Falc that adorned the cover of Scootering number 361. I asked for his help.

I told him I wanted my Vespa to have a strong, reliable engine — not something that would let me pop wheelies around the town hall or beat the land speed record — but a new beating heart.

“Give me two months,” Cristian drawled in his best doctor-to-patient’s worried relative voice, and you’ll hit the road again at the beginning of spring like never before.” I must admit that this made me a bit nervous. The previous engine was able to stack up 12,000km in a year just following the Piaggio regular service operations. Did I really want to ‘hit the road like never before?’

I wasn’t able to overtake trucks on main roads before and my cruising speed was from 55-65kph, but I don’t remember minding too much. Then again, in Italy heavy goods vehicles have to stay right at 70kph on the bigger country roads so as you can imagine very often I was a pretty easy target. I suppose if I’d ever encountered a drunken truck driver it might have been a different story. I could have been writing these words from the confines of my own hospital bed. I resolved at that moment to leave it all in the capable hand of Mr Cernettig — although only after making absolutely certain that he understood all my requests: okay, cruise speed from 75-85kph, reasonable fuel consumption, good reliability and the ability to confidently tackle mountains and hairpins. Was I asking too much?

Get on with it

A few weeks later I got a call from Cristian’s garage while I was climbing Stelvio pass at 19kph in first gear for a photography job. I could almost hear him smiling when he said: “I have the project all mapped out on paper Christian! Come see me and if you’re happy I’ll get going on it.”

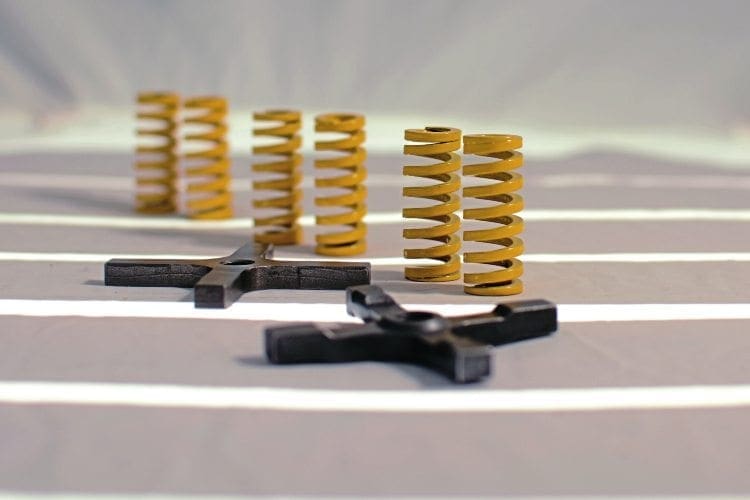

Sweet words. Something close to relief, or maybe hope, washed over me. Maybe my scooter would pull through after all. This was his proposal: start off with a standard 200cc Vespa engine, port it, then feed it up on a 225cc Polini kit, a 60 Polini ‘Corsa’ long stroke crankshaft (you can choose between a 57 for a 215cc or 60 for 225cc), reinforced bearings and gear selector, Polini primary drive and a few other juicy items. I listened intently as he reeled it off. Was it the cure my Vespa needed? He was so convincing that my confidence soared. This was it — the very makings of a rebirth for my beloved friend.

I had no hesitation in approving his choices and my mind wandered to thoughts of this mechanical wonder fully installed and thrumming away beneath me, out on the open road. How soon would I get to road test it? Not soon enough!

I have always believed that the best test for an engine is a road test — not simply running while strapped to a bench. All morbid thoughts now behind me, I began feverishly to plan an epic voyage that would really stretch this engine’s legs — a journey from my home to Rome, about 2000km, passing through the Apennine mountains, near San Marino, and onto one of the most dangerous roads in Italy — the SS309. Known as the ‘Romea’ it was named the nation’s deadliest route in 2006 with an incredible 1.7 crashes per kilometre. And it’s only a short road too, just 126km. Why would I be crazy enough to take my Vespa, still recovering from its transplant operation, on this widow-making stretch of Tarmac? It’s because here is one of the few places where you can find almost every sort of vehicle known to man — from little three-wheeler Piaggio Apes to super heavy trucks. I remember one time I was overtaken by a huge semitrailer carrying a tank! Perfect testing conditions.

New life in the old beast

I didn’t have long to wait. Cristian called me right on schedule to arrange delivery of the patient. When I saw it I held my breath as my eye lighted upon what was clearly an SIP ROAD muffler but then breathed again: everything else was just as I wanted it. No other visible signs of modification — just the beautifully familiar Vespa chassis gleaming back at me.

Cristian was grinning happily, proud of his handiwork. “We used a 28mm Dell’Orto carburetor attached on a Malossi reed-intake,” he enthused, before adding a cautionary note: “Now it is still being run-in so don’t push it too much, try to change the cruise speed as much as you can and sometimes go flat-out for a few seconds, just to understand how it feels. Have a nice day, see you in 1000km for a fine-tune.” That was it.

Once again, I was swept along by his confidence — all I had to do was follow his orders. How simple was that? Then the first gift the new engine gave to me was a bloody scar on my right calf. Sitting on the seat, a slight kick of my heel was fine to turn on the previous engine, but this one barely moved. It’s not a problem, just damn good compression, I told myself.

The pain of my new leg wound disappeared when I started riding; just as Cristian promised, I was able to cruise at 70-75kph using less than a quarter of the throttle. This alone was enough to plaster a big smile on my face. I must have covered 600km of regional roads as I explored the machine’s abilities. It was a completely different feeling to before but I never pushed too hard. A few weeks on, I loaded up the ‘Negra’ (the name will never change no matter what) as usual and left my office en route for Rome. Nothing really remarkable happened, despite the fact that I was now able to follow the traffic flow, taking advantage of the trucks’ slipstream to save a bit of fuel. I made an overnight stop in Rimini and the following day I was climbing the eastern section of the Apennines — the best road to reach the capital by scooter from the north.

At 12.35pm of the next day everything changed. Having gently nursed my steed for more than 1000km from the point of departure, I started to gently push it. From that moment on, the Vespa literally took off. I could climb uphill in third gear carrying 20kg luggage or overtake cars just after a hairpin flat-out in second/third gear. It was a revelation!

During the downhill stretches there was a whistle from the clutch and in a few moments I founded myself diving like an RAF Spitfire in 1943.

Despite all this enthusiasm though, there were some niggles coming through. I felt a couple of swerves during the corners, the fuel delivery was too rich, and the cruise at 50kph was uncomfortable due to engine vibrations.

My concerns boiled over when I reached Rome at last and realised that the left rubber shock mount which stops the engine from vibrating by means of a long bolt had collapsed, despite being new, just 1500km after the engine being installed. Not good. And now that I was in Rome, I wanted to check just how much power my Vespa’s new heart was pumping out.

Mr Marri helped me with a run on his dyno and the result was no surprise: 19.17hp and 25.51Nm torque at 5544rpm. I’d wanted an engine designed for reliability and that means low revs. With a lot of tweaking it would be possible to squeeze it to its limit and extract 28hp, I’d been told, but… what for? Fuel consumption is more important to me than outright power during my long-distance travels. I returned back to base a couple of days later with a lot to think about (having clobbered all the trucks hard on the way back — what a pleasure!).

Health checks

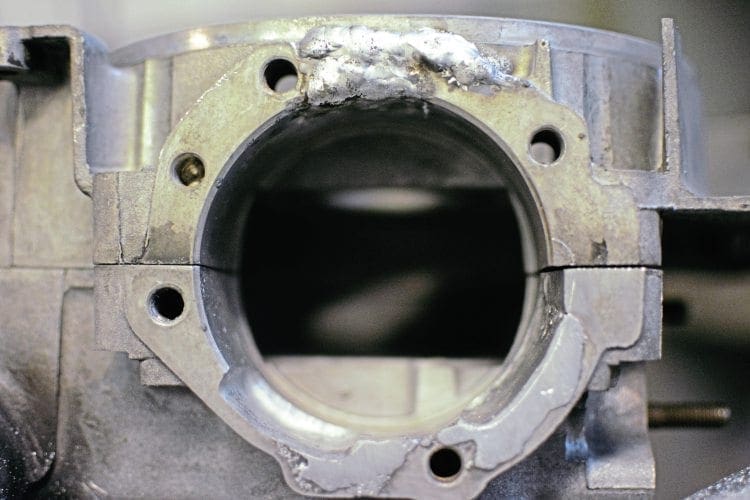

I decided to use my Lamborghini endoscope to check inside the combustion chamber without unbolting the head and I didn’t like what I saw. It appeared as though the second ring was sticking in its seats already and a slight brown mark was burned onto the cylinder. Time for a post running-in checkup at Cristian’s garage. Here is what we discovered:

- The burn on the cylinder was very light and due to bad oil quality. I used a well-known Italian brand for 650km and after a chemical lab-check it turned out that it was not 100% synth as explained in the label, but 100% mineral and of bad quality too.

- The stock engine rubber mounts were not able to resist the new amount of torque. As a matter of fact, when the Negra was rolling on the dyno and the operator opened it to full the throttle I actually saw the rear wheel move a bit on the left.

- Even at 65% of power capacity the engine was much too crabby in low speed due to the super-light flywheel of the Vespatronic. For now we decided to increase the squish to 1.4mm and to change the timing start point from 25° to 23° (Vespatronic).

- During the final part of the trip back from Rome I heard a knocking when the tank fuel was particularly low. A membrane-fuel-pump was in order to maintain the fuel line pressure.

- After the fuel-pump was mounted a recheck of the carburetion was needed, adjusting the main jets and leaning the ratio.

All this brings us up to today and 2821km on from when the engine was built — after at least a couple of dozen checks and tunes. Thanks to a new pair of rubber shock mounts the behaviour of the Negra in the corners is very stable; I can open it up to flat-out just before the end of the bend and it’s stable… although, I was now feeling strong vibrations through the floor right under my shoes. The stronger the engine mounts, the greater the vibration that occurred. The problem was solved with a change of my shoes and a modification to the plastic floor covering.

I was able to do 230km on a single tank of fuel with my stock engine; now I’ve lost 50km, although it is a great fun to ride and, I must admit, much safer in terms of keeping up with traffic without always being overtaken by huge trucks when traffic gets heavy. Plus I’m now preparing for a big trip to Armenia which I think will take two years and involve riding at least 40,000km on gravel, tarmac, sand and probably mud. I really don’t think the older engine would have made it.

It’s a bittersweet feeling — as though I’ve lost an old friend and gained a new lover, but that’s life with a scooter.

Words & Photographs: Christian Giarizzo