Novelist H G Wells wrote The Time Machine in 1895 the story of a man who can navigate the time streams on a machine made of nickel, ivory and quartz — and climbing the stairs at Casa Lambretta museum is like climbing aboard that improbable contraption. In just a few steps you are catapulted into another era. As soon as you reach the first floor, the journey begins…

Casa Lambretta is divided by time period. The first part of the museum collects the machines that were produced before the Second World War, while the central part covers the immediate postwar period up to the end of the 1950s. It is further subdivided by geographic area — sections where precious machines from France, Japan, Germany and Austria can be discovered.

“The scooter museum was created to collect the stories of many models, not only Lambrettas,” says Vittorio Tessera, the museum’s passionate founder and curator. The building’s internal space has been carefully designed and illuminated to Vittorio’s exacting specifications, allowing visitors to observe the scooters from multiple angles by simply walking around them.

The rarest exhibits are presented alongside the commonplace, allowing the curious to view their contrasting features side by side. Different styles, the work of different designers and the technological innovations of different historical periods are indicated and explained. Years pass by with each step through this hall of time until its pathway leads me to a structure studded with photographs, at its precise centre a striking three-dimensional representation of the Innocenti factory that draws the eye with its own form of visual gravity.

The Lambretta story has reached its conclusion and I am adrift until, knowing my particular interest in Vespa, Vittorio smiles and offers me the beginning of a new tale.

“I think I’ve discovered how the Vespa project idea was born,” he explains matter-of-factly. I stop in my tracks and eagerly pull out my notebook as if I were a reporter on the front line about to get the scoop of a lifetime. Vittorio gestures at a small scooter to his left.

“I remember when I brought this home, a little 1940 scooter labelled Belmondo. If you look closely, conceptually it recalls the ‘Paperino’ prototype produced by Piaggio. During a rally in Genova an old man approached me and said that he knew very well this little machine and had in fact owned one himself. I was sceptical, since as far as I knew there were no others around.

“The next day we met again and he showed me his photos. Amazingly, it was the same scooter, the one he drove such a long time ago. This old man was a former aircraft pilot and during his time had flown three-engined Savoia-Marchetti planes on duty in the Sicilian sky, bombing Malta.

“During his military service he became friends with a count — Carlo Felice Trossi, who had been a famous race car driver and builder during the 1930s. He had used this little ‘Velta’ machine for getting around inside the air base. After the war, Count Trossi returned to his native town, Biella, and presented the scooter to the old man as gift.”

Vittorio takes a moment to adjust his shirt before continuing: “I was interested in Trossi and while researching his life I discovered an account of how, during the wartime evacuation of Biella in 1944, for one reason or another, his family had played host to the management of the Piaggio group.

“This scant evidence took on greater significance when, during an exhibition in Biella, I was approached by Trossi’s grandson who had yet more photographs of this unusual scooter. They dated from 1944 but were, unbelievably, in colour. From the image composition they had evidently not been taken for fun — these were shots intended to show the little machine’s features clearly.

“The photographer was attempting to show how it was built — the same model you see now at the museum. So there is a front pic and a side pic in addition to others that are aligned perfectly perpendicular to the subject. Does all of this ring any bells for you?”

I am still confused. Entirely unfazed by my uncomprehending frown, Vittorio continues, his enthusiasm growing with every word: “Let’s move to southern Italy now. The only 100% functional and original ‘Paperino’ except for the one preserved at the Piaggio museum was found in Sicily. My friend Mr Donati of Piacenza bought it and we began the restoration together, carefully starting to dismantle the machine. We could hardly believe what we found. Underneath the hull, barely skin deep, it was the almost exactly the same as the little Belmondo scooter here.

“Everything reminded us of it — the fender brackets, the three-speed gearbox, the forks and the front-shield of ‘Paperino’, the latter being attached at the front by means of screws to the existing frame. When you put all these things together it takes you towards a surprising conclusion: I think what you’re looking at is the mechanical inspiration for the prototype which led to the Vespa — from which it all started.”

Now I understood. Trossi’s Belmondo airfield runabout had been carefully studied, becoming the inspiration for Piaggio’s ‘Paperino’. The sensation you feel when you see a machine of such importance is quite thrilling I must admit. Vittorio looks at me again with a twinkle in his eye. It is clear that he is preparing to deliver the last of his ‘hot news’.

“The tale is not quite finished yet though,” he tells me. “One of the most recent encounters I have had concerning this scooter took place in Cuneo, during another rally. Again one more old man stood for 15 minutes against the Belmondo machine and after that claimed that he built it. ‘This is huge!’ I thought. Later on we met at his house and he was right, he showed me his work contract with the Belmondo factory and all the photos. But this is another story to tell, for another day.”

Exploring a museum of this type with its owner and designer can be an amazing experience. Vittorio never seems to tire of telling stories, revealing the historical evolution of scooters as he does so. Every corner of this place is a memory of his life, a special encounter or a curiosity. This is not a single time machine but many machines that stand apart from the passage of time, allowing the visitor to traverse eras by doing nothing more than walking from one display to the next. This gentle form of ‘time travel’ is something every aficionado must try once in their lifetime.

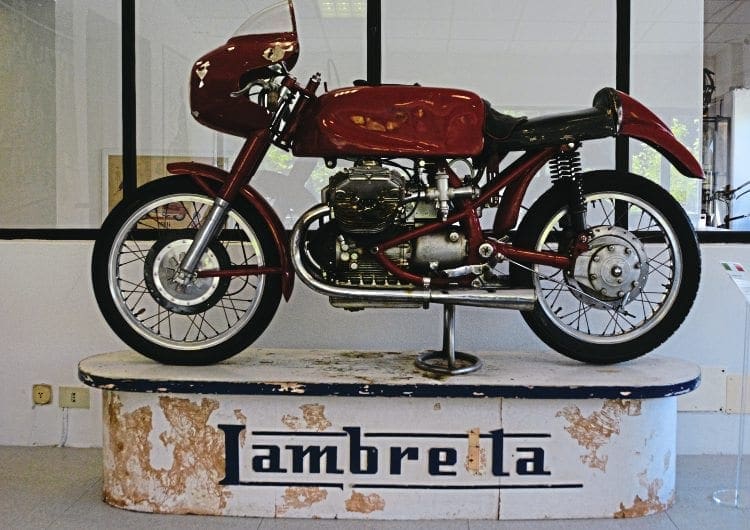

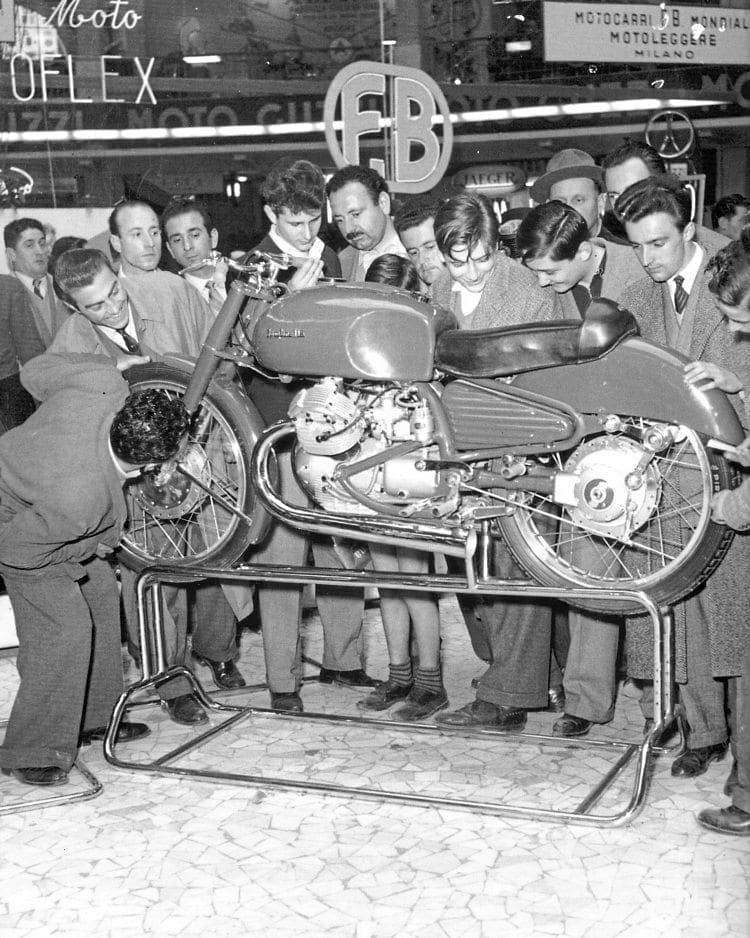

Entering the Lambretta section once more, I must decide what story I would like to listen to from Vittorio. He waits patiently as I cast my gaze across the neatly arranged machines. I catch sight of a motorbike-style example that looks quite different from the museum’s more familiarly Lambretta-shaped repertoire. We advance towards it in silence until, standing in its presence, I glance at Vittorio and the story begins.

“You chose a peculiar model,” he says, approvingly. “People when they see it do not even think is a Lambretta, but it is indeed. This was one of the finds we made at the old abandoned Innocenti factory — a 250cc, five-speed race bike.” Vittorio directs my gaze to a large photo on the wall just in front of the machine and starts by explaining the main differences between the machine it depicts and the model in the museum.

“Changing the head to DOHC, the preproduction version had two magnets: one forward, one behind, and then they managed to place just one magnet. In the first series there was a torsion bar as rear suspension, in the one in the museum there are cushions, the oil radiator was separated and the tubing holes were separated and after they have applied the radiator under the casing.

“The gearbox is a gem and a bit strange actually. There were only four gears in the preproduction model. You can see here the four-gear lever in the same position but there is another mechanism on the opposite side too. Strange indeed. This is the fifth gear. The rider, racing at Monza for instance, would push the fourth all the way up to maximum torque before he inserted fifth to have even more speed.

“The downside of this solution was that if he wanted to reuse the other lower gears he had to turn off the fifth level and switch back to the main set of four. The bike, however, does not seem to have been particularly successful because it did not win anything important. The project was designed by Giuseppe Salmaggi — Gilera designer — who at the time was working with Pierluigi Torre (Innocenti racing director).

“It would seem they realised that, at that moment in history, scooters were undergoing their greatest development in terms of production and in terms of attempting to create a product that people would want to buy. On this basis, the racer may have caused some internal friction between individuals who saw the company’s future moving in different directions. This bike-like Lambretta was a divergent branch of evolution that the company decided, eventually, it did not want to pursue and the whole project was terminated. We have to remember that this was 1952 — after the war had left Italy on its knees. Innocenti saw that its greatest chance for success lay in providing customers with what they needed and so it focused on small machines, machines that would help Italians to start their normal lives again.”

I cannot help myself — I want to explore more of the museum but, time machine or not, my time has run out. It is as though the stop button in the time-machine dashboard has been pressed as we descend the stairs and the present rushes back up to meet us.

We are greeted by a big smile from Vittorio’s son, waiting below like an emissary of the here and now, welcoming us back. I leave Casa Lambretta with a tremendous admiration for Vittorio’s immense passion and unfailing persistence. He has been able to create a place, free to enter, which educates visitors and intrigues the mind. Thanks to him, we can walk through not only the Lambretta story but that of the scooter itself.

Words & photographs: Christian Giarrizzo