Read the service manual on your RB250 Lambretta or Malossi 220 Vespa recently? No, because there isn’t one. Darrell Taylor has spent hours extracting the service data from comparable engines of the ‘Big 4’ motorcycle manufacturers. The results go a long way to explaining why scooters might have a bad reputation for being seen broken down on the roadside!

Following on from last month looking at two-stroke development and feasibility, learning from two-stroke development history of the big manufacturers, we found some meaningful data when converted to BMEP figures that can be seen in different engines. The figures produced show engines in different levels of development/tune and how they increase when they progress from road, to enduro, to motorcross, to road-race applications. Something, however, which is often missed as a consideration when these increases in power output are made or being pursued, is the increase in maintenance and service requirements as well as the reduction in lifespan of components used.

Performance levels of road going scooters have been steadily progressing over the years, more so in recent times where sprinting and race engine development has pushed performance levels to extremes never seen before. The situation is further developed by kit manufacturers in the small automatic scooter sector and small frame Vespa sectors, producing hyper-race kits that deliver off the shelf road race levels of performance. We are finding some of these kits making it to the road — with the purchaser, perhaps unwittingly, not understanding the levels of maintenance and limited lifespans of such designs. Often there is a misplaced belief that because a product is expensive, or a build costs a lot of money to produce, that it will therefore be as reliable as their standard TS1 (Lambretta) or Polini (Vespa) which previously covered 10,000 miles without a problem.

So the BMEP figures we deduced last month can provide us with definitive performance categories, and these can give us (with lots of research) the industry service schedules attached to them, in order to provide us with reasonable service and lifespan indicators. The question may be asked: are they comparable though? Should they be reduced/increased due to running conditions, design etc? Well let’s see…

How do Yamaha do it?

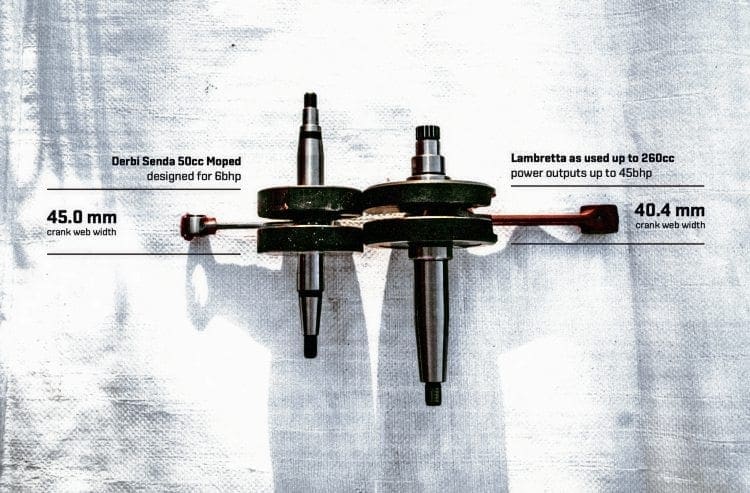

If we consider that a motor produced by Yamaha, like the road-going DT250, running on an oil pump, with a wide webbed crankshaft, large cooling fins on cylinder/head, a thick cylinder liner which resists distortion, a well-designed air-filter system, an advance/retard ignition, and a motor that’s fitted in a position running in open air… then compare that to a Lambretta RB250 or Malossi 220 on premix oil, with narrow crank-webs that are not even as strong or wide as a 49cc moped crank. There will be small cooling fins on cylinder/head, thin cylinder liner, an open carburettor, static ignition timing and it’s all running under tight body panels which retain heat.

Consider that the carb’s breathing hot/ dirty air produced from the engine, with a rear wheel distributing road dust etc. that is sucked in by the flywheel, pushed around the cylinder cowl and fired out for the carb to now suck it back through the motor, and it’s not a pretty picture is it? Unless some of the motorcycle attributes are applied to the scooter maintenance applications, then we are looking at significantly more frequent maintenance regimes being required on tuned scooters.

Fit for purpose?

We can also look at what the bike’s being used for. The Yamaha DT is an urban runaround while offering the ability to do a bit of ‘green-laning’. If a motorcyclist wanted to tour he would simply buy a touring bike fit for purpose, which Yamaha recognises by producing different machines for different tasks. However the average Vespa/Lambretta scooter is often tasked with many different purposes, be it daily commute, urban runaround, long distance tourer, rally machine, local hooligan grin factor machine, sprint scooter, road-race scooter, and so on.

Sometimes the scooter has it all to do because the cost of the machine is prohibitive for most consumers to have one of each that does each job well. The result is that compromises often have to be made to try and tick as many boxes as possible to produce a good all-rounder. With this in mind, the average scooter should therefore be similar in performance to that of the DT250 and with many scooters sat around the 20bhp mark used for a wide range of non-sporting duties and display good levels of reliability, it’s no wonder kits/packages like this succeed in satisfying customer’s needs. Current scooters have surpassed the performance levels of their motorcycle equivalents of yesteryear which can be seen if you check the BMEP comparisons, but we haven’t caught up with maintenance practices!

BMEP reminder

Now would be a good time to recap on some BMEP figures, and I’ve added some Lambretta and Vespa figures for comparison. From these figures, service and lifespan indicators can be allocated. There’s also some other interesting observations I found while pulling the info together and doing the research…

| Air-cooled standard road/touring kit around 6 bar | |||

| Vepsa T5 125 | 11bhp | 6500rpm | BMEP = 6.07 bar |

| Vespa PX 210 Malossi | 20bhp | 700rpm | BMEP = 6.1 bar |

| Gilera Runner 180 | 19bhp | 8000rpm | BMEP = 6.05 bar |

| Lambretta Imola 186 | 19bhp | 7500rpm | BMEP = 6.1 bar |

| Lambretta TS1 225 | 22bhp | 7500rpm | BMEP = 5.98 bar |

| Yamaha DT 175 | 16bhp | 7000rpm | BMEP = 5.85 bar |

| Yamaha DT 250 | 18.2bhp | 6000rpm | BMEP = 5.44 bar |

| Air-cooled road-tuned or endure engine circa 7-8 bar | |||

| Vespa latest 144 kits | 20bhp | 8000rpm | BMEP = 7.78 bar |

| Vespa latest 172 kits | 22bhp | 7500rpm | BMEP = 7.64 bar |

| Lambretta (tuned) RB20 | 28bhp | 8000rpm | BMEP = 7.92 bar |

| Lambretta (tuned) RB250 | 35bhp | 8000rpm | BMEP = 8.04 bar |

| Yamaha IT200 | 27.6bhp | 9000rpm | BMEP = 6.87 bar |

| Yamaha IT250 | 32.2bhp | 7500rpm | BMEP = 7.65 |

| Air-cooled Lambretta/Vespa race-tuned kits vs Honda water-cooled endure circa 9 bar | |||

| Vespa latest 144 kits | Tuned 26bhp | 9000rpm | BMEP = 8.99 bar |

| Vespa lastest 172+ kits | Tuned 30bhp | 9000rpm | BMEP = 8.69 bar |

| Lambretta RB20 | 34bhp | 8750rpm | BMEP = 8.8 bar |

| Lambretta RB250 | 40bhp | 8500rpm | BMEP = 8.89 bar |

| Honda CRM250 | 40bhp | 8000rpm | BMEP = 9 bar |

| Air-cooled Sprint Lambretta circa 10 bar vs water-cooled race MX/Extreme Race | |||

| Yamaha YZ250 | 48.8bhp | 8800rpm | BMEP = 9.94 bar |

| Lambretta RB250 | 45 bhp | 8500rpm | BMEP = 9.42 bar |

| Water-cooled race GP bike 11+ bar | |||

| Honda RS125 | 38bhp | 12,000rpm | BMEP = 11.35 bar |

Compare motorcycle and scooter service data…

Let’s start with the worst case scenario of trying to run an 11 bar spec motor like the Honda RS125 GP bike on the road with all its bells and whistles and state of the art two-stroke design that Honda could throw at it. It would be great fun and completely mental on the road, blasting around on a GP spec bike or, by comparison, a GP engine level of power output in a scooter!

Full race-spec motors like this, quite surprisingly, are available from various Italian manufacturers as hyper-Vespa engines. They are produced to cater for the keen interest in sprint and short track circuit racing, which has seen development pushed to the limit. If these scooter units are compared to the Honda service data, this should be relevant, although most are only air-cooled units and can only realistically sustain the short sprint or race distances that they are designed for. Below is the service data from Honda for their power unit, as taken from the official Honda manual:

Honda RS125 (Nikasil) water-cooled GP race bike (11 bar)

With richer jetting settings keep to the following for break in/running in:

Below 7000rpm for 30 miles

Below 8000rpm for 10 miles

Below 9000rpm for 10 miles

Below 10,000rpm for 10 miles

Total 60 miles break in: then strip down top-end to clean off any high spots or ridges with fine 600 wet n’ dry, check ring for sticking around exhaust port, and chamfer edges/free off if required.

Component lifespans:

Piston: 240-300 miles total including break in time

Piston rings: 240-300 miles

Piston pin: 600 miles

Con-rod and small end bearing: 600 miles

Spark plug: 600 miles

Clutch friction discs: 600 miles

Gear oil: first at 60 miles then every race

Chain: 600 miles

Particularly fast wearing parts are as follows:

Cylinder head 0-ring

Reed valve

Clutch springs

Drive sprocket

Engine mount rubber

Spark plug

Clutch plate

Interesting points noted by Honda:

Premium gasoline with research octane number of 100 may be used, if knocking or pinging occurs try a different brand or a higher octane grade.

If gasoline/oil mixture is left standing for a long period of time, lubricity will deteriorate so make sure it is used within 24 hours!

Once an oil container is opened it must be used within one month since oxidation will occur.

So if we were to try and run such high-spec, 11 bar scooter motor on the road long-term, and decided to try doing a popular scooter rally… well, a picture explains it better.

Yamaha YZ250 (Nikasil) water-cooled, Motocross (10 bar)

With a 578-page manual to work through this one really brought home that you will spend more time working on this machine than you do riding it if you follow the operating instructions fully.

With a whole section titled ‘Pre-operation inspection and maintenance’ which is to be followed each time the machine is ridden, then when returned to start again with storage instructions (including draining off fuel, and oiling the bore via the spark plug hole that every manufacturer seem to request us to do) I’ve noticed in this exercise, it becomes apparent how detailed the maintenance is.

Break in/running in: The time is down as one hour on a new motor or 30 minutes on just a piston kit, so works out a similar time to the Honda GP bike. It also goes on to say you should then strip the top-end and remove any high spots on piston or deposits on cylinder with 600 wet and dry. Premium unleaded fuel is quoted on this newer manual of 95+ but warns if knock or pinking occurs to try different fuel or a higher octane. This one appears again too: no premix to be used which is more than a few hours old (how long has your fuel sat in your scooter since it was last ridden?!).

Aprilia RS125 (Nikasil) water-cooled, production racer (9.5 bar)

Break in/running in time is 1000 miles. For the first 500 miles, never exceed 6000rpm. From 500 to 1000 miles the max is 9000rpm but in short bursts only. At 1000 miles the max is 11,000rpm.

Maintenance: At 5000 miles, strip and de-coke check and inspect/clean or replace piston at 10,000 miles piston kit and linings. No data given for crank or con rod life just acceptable tolerances to work to while it’s apart for check and inspection. A whole host of checks and inspections are listed with the below items of note:

Carb clean outside and adjust at 600 miles.

Carb clean throughout at 2500 miles.

Clutch check at 2500, replace if required of at 5000 if not.

The air filter needs cleaning at 2500, and at 600 miles the plug needs a clean/adjust or replacement.

Oil change 600 then every 2500.

Chain adjust 300 miles.

Storage instruction it not used for 20 days or more: remove plug and pour 5-10cm of two-stroke oil in through the spark plug hole then turn over engine to lubricate the cylinder/piston/rings etc.

An instruction on riding style was included too: Do not open throttle fully if engine speed is low!

I’ve found this leans out jetting if you do this as the motor labours to pull through the lower/midrange delivering lots of air but without the engines progressive rpm enrichment to draw the fuel, many 70s and 80s two-stroke bikes contained similar instructions within user manuals that have been forgotten or today’s riders are not aware of.

Scooter service schedules

Now we have the highly strung racy, water-cooled, 9+ bar machines out of the way and have built an understanding of work required and life expectancy of parts when pushed to extremes. It’s quite often the case that racers will ignore the schedules and work on a strip and inspect basis and push the parts to their maximum life expectancy, but this comes with the risk of a more costly failure: if a con-rod fails and punches through a crankcase and cylinder then there’s a few grand gone straight away.

Below are some notes regarding more standard type machines around the 6 bar range. Later model T5 Vespa and Gilera Runner 180 models had performance benefits over the relatively low powered SIL200 and Vespa P200 standard models, however the service data is again lacking for these models. With the exception of what I considered early top-end strip down and de-coke required at 2400 miles, that provides the opportunity to inspect and check all other pads at the same time and replace where necessary.

Gilera Runner 180 auto (Nikasil) water-cooled commuter scooter (6.05 bar)

Total break in running in time: 600 miles. Servicing is quoted as 2400 miles or annual but detail is lacking. Storage instructions appeared here again as: oil down plug hole, drain down tank and float bowl of all fuel.

Vespa 15 125 (Nikasil) air-cooled commuter scooter (6.07 bar)

Total break in/running in time: 600 miles. Oil change after first 600 miles, then 4800. Top-end strip/de-coke at 2400.

Vespa P200 cast iron, air-cooled commuter scooter

Oil change 480 miles, then 2400 top-end de-coke. Storage instructions appeared here again as: oil down plug hole, drain down tank and float bowl of all fuel.

SIL Lambretta GP200

Oil change 450 miles first, air filter clean 600 miles. Storage instructions appeared here again as: oil down plug hole, drain down tank and float bowl of all fuel.

The key figure for Vespas and Lambrettas

The most common performance level these days is the 6 to 8 bar range where a balance exists for a multi-purpose all-rounder which, engine size and rpm-range dependent, can sit somewhere between 125cc at 11bhp and 250cc at 35bhp. It’s in this range I aim to produce a modern day service schedule for Vespa and Lambretta scooters, in the next instalment. I will be also be speaking to some of the kit manufacturers to get their input on service and lifespan, along with any service schedules or info they may have put forward for their own products.

DEPENDS WHAT YOU WANT IT FOR, MATE

How can a single given engine size be suitable for so many different applications?

If we pick out Yamaha as an example, we can see the sort of clever development strategies manufacturers employ. The starting point is a 125cc single cylinder engine, which was originally put together as an air-cooled unit. In its lowest rpm power form but with higher torque and a small carb it works as a TY model trials engine.

When given a tweak which results in different specs, it becomes a DT road-trail model. Moving steadily up the rpm range and with a little more power squeezed out it becomes the RS road model. Then for enduro use it becomes the IT, then onto the YZ Motocross, and finally evolves into a liquid cooled TZ race model.

The evolution goes way further though, as 100cc derivatives and bigger 175cc versions are developed up to 200cc for use in quad bikes including the Blaster IT and WR variants, with a final DT 230 single with origins from those early designs.

Then the units are built as twins to create 200, 250, 350, and 400 versions… right up to four-cylinder race TZ700 and TZ750 models. It’s an incredibly diverse lineage to come from such relatively humble beginnings.

The same evolution applies to scooter engines with the various bore-stroke combinations, but the power characteristics are fine-tuned too, with some kits sold as standard replacements, some as tourers, some for racing and others as hyper-race versions. There are a whole host of variations and combos that can produce a broad range of riding characteristics and an increasingly difficult choice for the customer to make.

Thankfully many years have passed and an evolutionary selection of these components has risen. While some have fallen by the wayside and their production runs have ceased, old faithfuls like the TS1 kits and some JL exhausts with 30mm Dellorto cats etc. are time-served options, and generally safe choices.

Magazines and the internet can place data right into people’s laps — everything from rider reviews to dyno tests, so a savvy consumer can hopefully make an educated decision about what they’re likely to need from what’s available. But often the glossy pics and dyno graphs don’t reflect the riding characteristics clearly — unless the consumer has a good understanding of power curve shapes and stats.

For example, an owner who has only ever ridden a standard GP200 at around 10bhp might, after his first ride of a 20bhp TS1, describe its performance levels as ground-breaking. While this may be true for him, if he tells his friend who already owns a 25bhp RB250 to buy one on the basis of his experiences then that friend is going to be left sorely disappointed.

Words & Illustrations: Darrell Taylor

Photographs: Paul Green & Neil Kirby