Engine transplants are nothing new, but getting them right is more art than science. After a decade of work Gunny is almost there…

Transplant surgery

In the mid-1980s Alan Rosser embarked on an ill-fated project to bring a Yamaha-engined Lambretta into production. That story is best consigned to history, but it left a lasting legacy. Having proved that such engineering was viable, the project stuck a chord with performance obsessed scooterists.

Fast forward a few years and Frank Sanderson, who had collaborated with Rosser in the early stages of development, successfully brought a far more refined product to the scootering masses under the Lambretta Innovations name. Ultimately, these hand-built machines led to the worldwide success that is Scomadi, but I digress. Let’s return to the subject of this article, Gunny’s incredible Yamaha RD350 powered Series 2 Lambretta.

“Before going any further with this story I want to make one thing clear,” Gunny emphasised. “When I ordered this scooter from Frank in 2006 I wanted a show bike, not a mile-muncher and that’s exactly what he delivered.” Like so many scooterists before him Gunny soon realised that looks weren’t enough — he wanted usable power and lots of it. What followed was a 10-year wrestle with overheating and reliability.

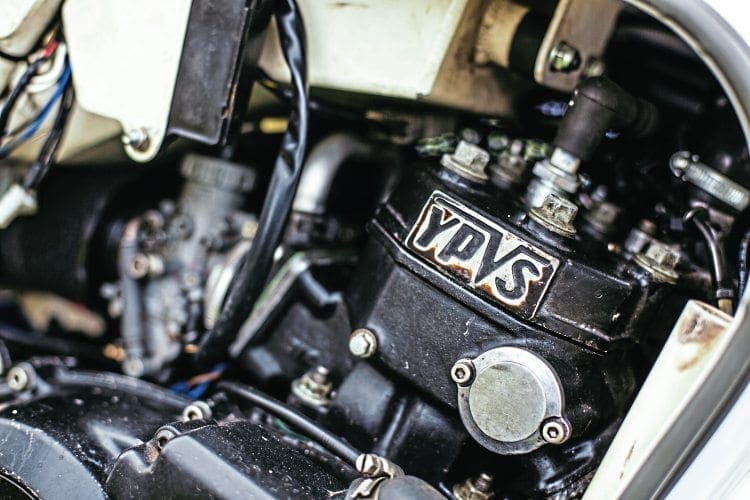

Lambretta Innovation’s products are instantly recognisable as Lambrettas, which in Gunny’s case, is the portly Series 2. Under the covers, however, it’s a very different story. Here a bespoke cradle houses Yamaha’s legendary RD350LC engine.

“I’d ridden RD’s before and wanted to unleash the engine’s power,” said Gunny, “Unfortunately I didn’t appreciate the complexities involved. In fact it became known as ‘Valhalla’, as the quest for reliability was mythical!”

Turning down the heat

The main affliction for Valhalla has been overheating — a problem that originates not from the conversion, but from Yamaha’s original design. Although triumphed as liquid-cooled, Yamaha’s legendary motor has always needed additional airflow to keep it at operating temperature. That’s fine in an open framed motorcycle, but once it’s encased in a Lambretta’s bodywork, temperatures rise dramatically. Simply putting the panels on raises the temperature by around 10°. There are some obvious ways to counter this problem, such as fitting the larger radiator from an RD500, but there were other, less obvious factors that contributed to overheating problems.

“The RD350 engine was manufactured in two variants, the F1 and F2,” explained Gunny, “and I’d challenge any scooterist to tell them apart visually. Although many components will fit either engine, they’re not interchangeable. For example, mine’s an F1 engine, but it was fitted with an F2 ignition system. Although it runs, they are incompatible and that leads to overheating.” Having tinkered away time and money, Gunny did what, in hindsight, he should have done from the outset – take Valhalla to a Yamaha specialist.

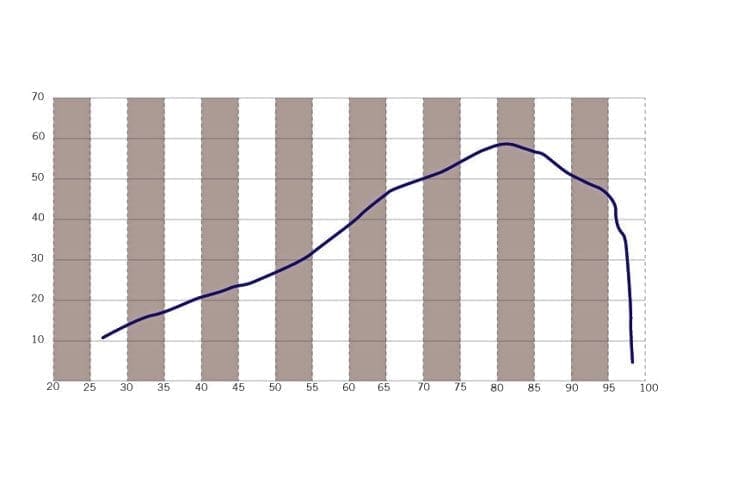

“Dynotech in Paisley have been superb. Their initial assessment took the engine from 35 to 51bhp. That was just sorting out the jetting, setting the ignition and getting the engine back to its standard specification. Their intervention was the start of creating a usable machine.”

Another source of problems from the original build was its electrics. The original loom was its Achilles heel,” explained Gunny, “as it was a marriage of Yamaha and Lambretta components. I commissioned a bespoke loom, which seems to have eliminated a lot of problems. Running it through the frame has also helped, as temperatures under the panels caused more than one melted wire!” Over the years Gunny has chipped away at Valhalla’s overheating problems with some efforts being more successful than others. A larger water pump, originally from a race bike, helped but in Gunny’s opinion the final touch was Adam Tassoman’s idea.

“The leg-shield vents were designed by Adam and I should have done it years ago. They’ve reduced the temperature considerably and he’s made a beautiful job of finishing them.”

Putting rubber on the road

Having spent the best part of a decade trying to create a reliable road-going scooter, there’s one obvious question to ask Gunny — what’s it like to ride? He laughs and replies in one word — “Awful!” After probing a little further it seems things aren’t quite that bad. “On motorways or dual carriageways it’s incredible, the power delivery is smooth and it rockets through the gears. It reaches 80mph at 4000rpm and, at that speed, is just touching the base of its power-valve. With the GPS showing 110mph, it had plenty left to give.”

On the dyno Valhalla’s topped out at 125mph but, as the tyres are only rated to 94mph, Gunny is reluctant to explore its top road speed. “On twisty roads it can be ridden like any tuned Lambretta, but open the throttle and it bites back. Unfortunately, the brakes aren’t too effective, in fact I think the main reason it slows down when I throttle back are the Series 2’s aerodynamics!”

Over the years Valhalla’s consumed five engines and currently sports an overbore that raises its capacity to around 380cc. The Yamaha factory figures for the 350 engine are 52bhp, a figure that Gunny’s improved to 59bhp at the rear wheel. Having finally solved the overheating issues, the biggest limiting factor is now fuel consumption. “The tank holds six litres, which means a range of about 30 miles. I’m getting well-known at the local petrol stations!” he said.

So, is this the most highly developed transplant scooter on British roads today? Possibly, but Gunny doesn’t strike me as a man to settle on one thing for too long. I’ll bet that this isn’t Valhalla’s final incarnation. Given the amount of time and money involved in achieving this level of perfection, I had to ask if it was all worth the effort. Gunny’s answer was unequivocal: “Nothing comes close, it’s worth every second of frustration.”

Sanderson and Rossa are names inextricably linked with the development of scooter transplants and perhaps it’s time Gunny was added to that list.

OWNER’S DETAILS

Name: Gunny

Scooter club & town: Black Widdas SC & MD 20/20 Kilbirnie.

How and when did you first become interested in scooters: Nearly 40 years ago.

What is your favourite scooter model: PX street racers or Series 2 street sleepers.

What is your favourite style of custom scooter: Well-engineered ones.

First rally or event: Yarmouth, Edwin Starr got attacked on stage, 1985 or 86.

How did you get there: On a PX 125. Two-up with no spare wheel or cables, very little money, a tent that leaked, slept in a bandstand and it snowed from Carlisle to Glasgow… Loved it…

Favourite and worst rally/event: IoW or HH, I enjoy myself at them all. I only go to see the scooters hence why IoW. I don’t care about the music or the bands playing.

What’s the funniest experience with a scooter: Getting stung on the bawsacks at HH.

What’s the furthest you’ve ever ridden on a scooter: Holland, IoW. I also toured southern Ireland for two weeks on a P2 in 1995.

Favourite custom/featured scooter of all time: The Rossa 350.

If you had to recommend one scooter part or item of riding kit, what would it be: Decent tyres.

What’s the most useless part you’ve ever bought for one of your scooters: The old swallow tyres when I was 17-18, dreadful…

SCOOTER DETAILS

Name of scooter & reason: Valhalla (it was that unreliable that it’s a myth).

Scooter model: Lambretta Series 6.

Inspiration for project: Rossa 350.

Time to build & by whom: Lambretta Innovations and it took three years to get it to the stage it was then.

Any specialised parts or frame mods? What & by whom: Everything has been modified in some way. It’s not till you sit it next to a standard Series 2 that you start to really notice things, even the horn cover and panels, in very small details.

Engine spec

Engine: RD350YPVS. F2 model.

Tuning: Barrels rebored 1 mm oversized. Custom exhausts by Lambretta Innovations.

Dyno: Dynotech Hillington – 01418 820632.

Power: 59bhp at the back wheel.

Top speed: Does over the tonne and sits at 85mph.

Gearing: 16×34, pretty close to a standard RD.

Paintwork & murals done by: Clan Customs.

Overall cost: It cost me 13k back in 2009 and it’s been rebuilt six times, changing paint, engines etc all just to get it where it is now. I don’t even want to think about what it has cost me altogether…

What was the hardest part of the project: Getting it reliable, as when I first got it, it had massive overheating issues. This is the sixth time it’s been rebuilt with the most holes and vents it’s ever had and it has a proper custom-built wiring loom, as the butchered RD one supplied was the Achilles heel of the scooter. Fingers crossed it gains a bit of reliability this time!

Do you have any advice or tech tips for anyone starting a project: Make sure you’ve got deep pockets. It’s a lot easier now to get info on building this type of scooter via FB… as we all share the trials and tribulations of owning these machines!

Is there anything still to add to the scoot: A portable centre tank that I can just slot on/off, as I only get 35-40 miles on a full tank now.

In hindsight, is there anything you would have done differently: I should have cut out the front vents years ago.

Is there anyone you wish to thank: Thanks to Adam Tasso scooters Edinburgh, even though he’s a Vespa man he got stuck into this thing when it had the overheating issues. Massive thanks to WuIlie and Martin at Dynotech Hillington for rebuilding rewiring and getting the thing back on the road.

THE LEGENDARY ELSIE

From the mid-1970s Yamaha played on its racing successes by marketing its RD (Race Developed) series of machines. However, it was the introduction of the LC (liquid-cooled) range in 1978 that transformed sports motorcycling for a generation of riders.

Known affectionately as ‘Elsie’, its 250 and 350cc engines offered affordable power wrapped up in iconic styling. For a few halcyon years between its introduction and the 1963 changes to learner rider regulations it was possible to ride a 250LC on 12 plates (although in fairness the 125 was no slouch). In 1983, while learner riders were still in mourning, Yamaha introduced its Power Valve System (YPVS). In simple terms this was a servo-controlled method of altering the height and size of the exhaust port at various engine speeds. This boosted power by around 10%, making Elsie the weapon of choice for budding street racers. The combination of speed and inexperience is rarely successful and for most of the Eighties it was possible to walk into any motorcycle breakers and pick up a mangled LC for a few hundred pounds. As its engine was reliable, powerful and offered opportunities for tuning, it became the powerplant of choice for transplant engineers.

Even as late production units approach their second decade of use, Elsie is more than capable of holding her own against more modern designs. A testament to its reliability and engineering are the number of ‘off-the-shelf’ scooter performance kits that use the LC piston.

Words: Stan

Photographs: Gary Chapman