The story of the first reed-valve Lambretta

A host of legendary names have been involved with Lambretta tuning and racing — Arthur Francis, Dave Webster, Ralph Saxilby, Ray Kemp and countless others. Mention Steve Saffin though and most will reply ‘who?’ But this man was ahead of his time and deserves his place in scootering history. Read on…

The man

Steve purchased his first Lambretta way back in 1966; a series 1 Li 150. It had actually been in his family since 1962 before being sold to a local friend in 1964. Steve bought it back some two years later. It wasn’t the quickest machine in the world and he was intrigued to see if it could be made to go faster one way or another. With very little knowledge in the art of two-stroke tuning and with very few publications available on the subject it wasn’t going to be easy. In the mid-1960s Lambretta tuning was virtually nonexistent or at best in its infancy and the idea of working on port timings, compression ratios, carburetion and jetting charts simply hadn’t been considered.

Any two-stroke will do

Devon is not noted for its racing history and certainly not for racing circuits, however the remote village of Dunkeswell did have an old airfield that was used for karting. It so happened that a friend local to Steve raced a kart there using a 200cc Bultaco engine and as a 16-year-old Steve would tag along and listen to everything he was told about tuning this already powerful two-stroke engine. Allowed to help on race days, it soon became apparent to Steve that the tuning techniques used on the Bultaco engine would also work on to a Lambretta. With those thoughts in mind, Steve did totally the opposite by buying and tuning a Messerschmitt CR200 instead.

Using a 200cc Sachs engine there was plenty of scope for improvement from porting work to completely overhauling the Exhaust system. Taking on board what he had learned from his karting exploits Steve significantly improved the performance of the Messerschmitt even though the standard brakes and suspension made for a scary ride. Feeling confident that his two-stroke knowledge was widening and that he now had the skills required to take on such a task, the next step would be to give the same treatment to his Lambretta.

Racing on the streets

Rather than pursue the option of tuning the Li15, for the grand total of £40 Steve purchased an eight-year-old TV175 series II; after all, its extra 25cc would mean more scope for improved power output. Having just moved to Taunton in Somerset during the spring of 1968, Steve soon met up with the local scooter enthusiasts, many of whom were interested in scooter racing. The racing scene was rapidly becoming popular and would be the ideal opportunity for Steve to put all his new tuning knowledge to the test. Despite working on several other Lambrettas, his real ambition was to tune and develop the TV175 he had just acquired.

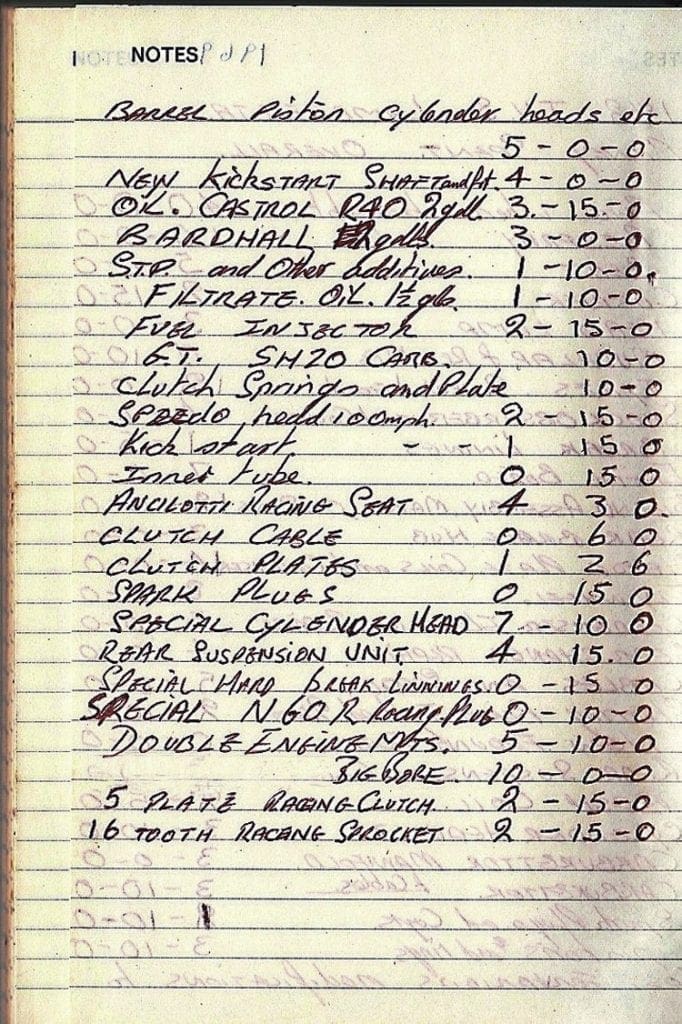

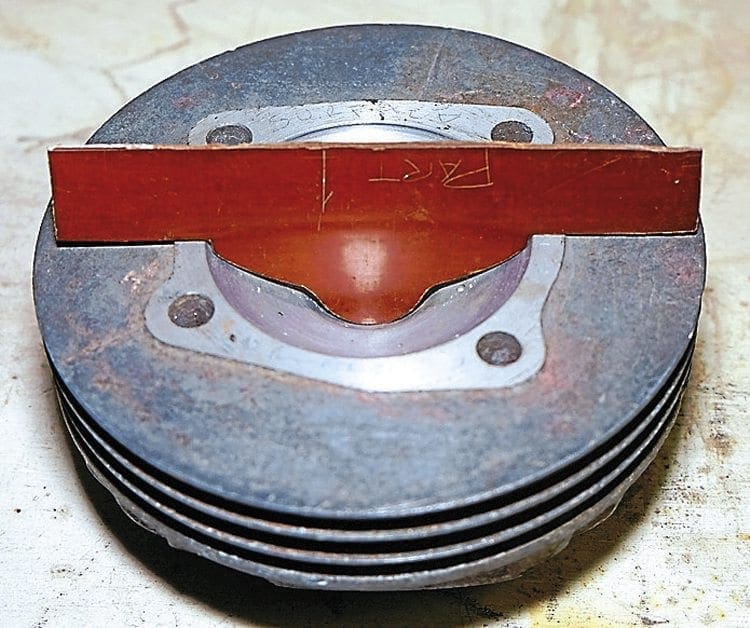

The first job would be to raise the capacity by boring out the barrel as far as possible. There were readily available 66mm pistons for this popular conversion but it did make the walls of the cylinder extremely thin. All the ports were subject to both rotary and hand filling to aid gas flow and the crank webs were padded with cork to raise primary compression.

The next stage was the exhaust system and with no aftermarket pipes available the existing one would be subject to major surgery. Cutting open the main box section, Steve repositioned the baffle to make an angled cone to the same contour of the outer section, while adding a larger down pipe, in a way similar to that of the modern day big bore exhaust. Attention was now turned to the stator and flywheel. The heavy fan was removed and in its place a quarter inch thick circular steel plate fitted which had a plastic fan directly bolted to it.

The condenser was replaced with an uprated capacitor acquired from a TV repair shop (remember them) and the latest competition coil made by Bosch. Next on the list was the cylinder head and by using templates made out of Tufnol, Steve was able to calculate a new profile which was professionally machined for higher compression. At the same time the original spark plug thread was welded up so that a central plug head conversion could be carried out.

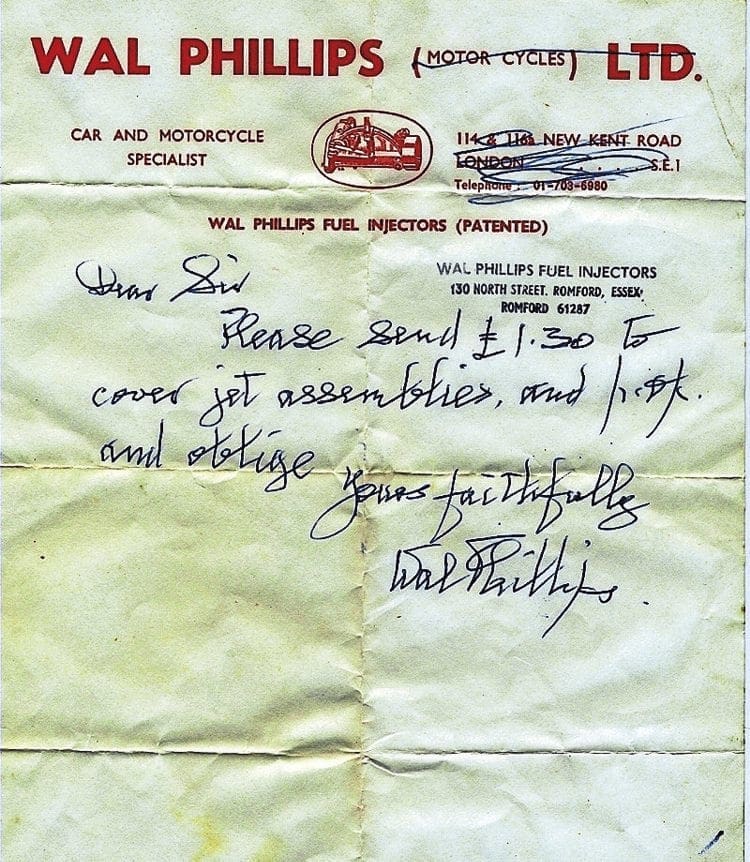

The final piece of the top end jigsaw was carried out to the carburetion and to as near perfect as possible. This was proving easier said than done as the injector had passed through several hands by this time and was in need of an overhaul, the only solution in the end was to contact the designer himself. After a brief chat, Wal Phillips invited Steve to bring the Lambretta to him to get it set up. After all, if he couldn’t sort it no one could. Replacing and balancing the butterfly valve cured any issues and transformed the engine’s acceleration.

With all the tuning work complete and the fuel injector set up correctly, now was the time to see if all worked. Out on the road the Lambretta gave an amazing turn of speed and acceleration. With no other scooters locally able to compete with its performance, Steve set about racing anything on two or four wheels around town. Classed as a street racer even back then, the idea was to make it live fully up to its name… and it did.

Beginner’s luck

Steve’s initial route into racing was through the National Sprint Association. Having joined the NSA in 1970 with a local motorcycle racer, they started attending sprint and hill climbs across the country, getting a real taste for speed at the NSA meetings, and this soon translated in to full circuit racing. Originally starting out as a mechanic and tuner for his friends whose engines he had been working on, Steve soon became eager to send his own Lambretta out on to the track. The already proven Lambretta was using tuning techniques that many had not seen before. Looked upon as a novice by many of those who were now seasoned competitors at scooter racing Steve had a point to prove. At one such race at Lydden Hill he did just that but not in the way anyone would have thought.

At the front of the pack from the first corner, Steve built up a huge lead in just two laps. Rather than continue though, he pulled in to the pits and left the remaining competitors to finish the race. Not only was it a show of superiority, but also a humiliation of the other competitors. The winner was left deflated, knowing he’d only won because Steve didn’t bother to finish. This kind of behaviour didn’t go down well in the paddock and Steve repeated the stunt several times.

As he further developed the engine by adding a five-plate clutch, various gearing alterations and continued porting work, the Lambretta became even quicker. With his antics of leading but not finishing a race continuing, the bad feeling in the paddock intensified. By now the machine was almost kept under guard to prevent potential sabotage and damage from other furious competitors. Realising the situation wasn’t going to be resolved, Steve opted to leave machine at home from now on and revert back to his role of supporting other racers as a their mechanic. His racing exploits once again concentrated on NSA hill climbs and sprints which again attracted adverse attention. This time it was due to the fact that a Lambretta could beat a motorcycle, something which had never happened before.

The first ever Lambretta reed valve?

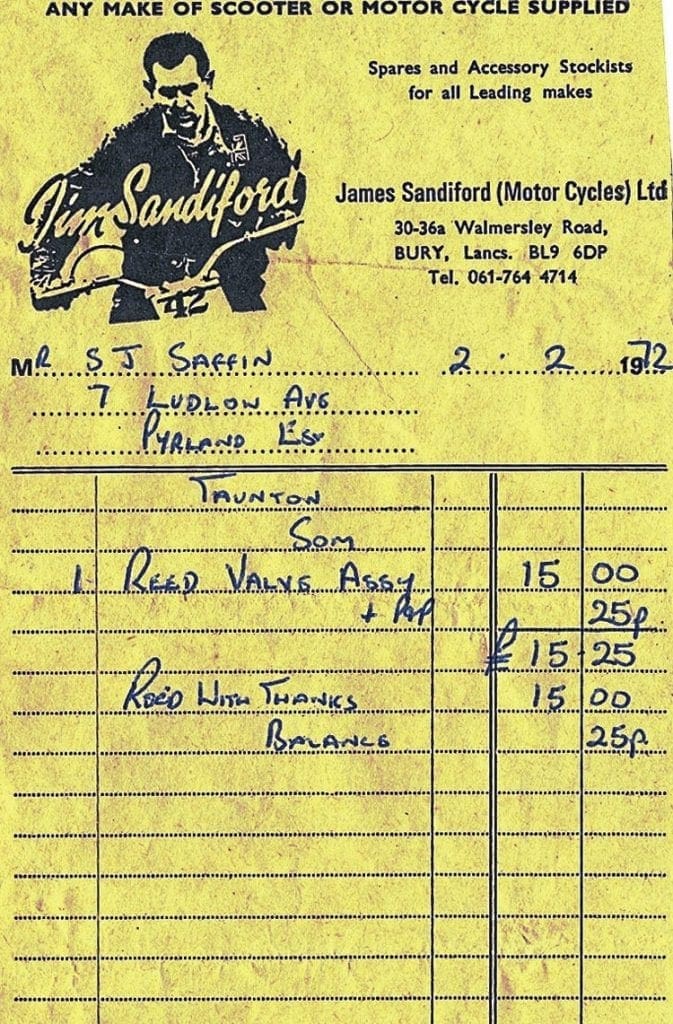

Still keen to learn more about two-stroke tuning and willing to use any method to improve performance, Steve read any publication he could to find out more information. By chance in 1972 he came across an advert in a motorcycle magazine for a reed valve conversion that quickly grabbed his attention. It was basic to say the least and inserted directly in to the carburettor manifold specifically designed to fit the Amal MK 1.

Without hesitation he ordered one and fitted the reed valve conversion and Amal carburettor to the engine. Though the device was crude it did give a slightly improved performance and was a worthwhile exercise. Soon after Steve had an adaptor made so he could fit the reed valve to a Dellorto 30mm carburettor, his preferred choice. Though the device worked to a certain extent Steve was sure if a reed valve could be directly fitted to the cylinder this would improve performance even further. Unfortunately there were too many restrictions in the design of the cast cylinder and awkward frame position to allow such a modification or so it seemed.

By 1973 Steve was working for a local marine company involved in preparing race boats. Working alongside the engineers who built the race engines, he noticed they used crank case induction through a reed valve. The idea was simple — do the same to a Lambretta engine. The problem though was finding the room to fit it. Having worked out that there was just enough space to make a port in the top of the crank case, Steve stripped the engine to start work on the conversion.

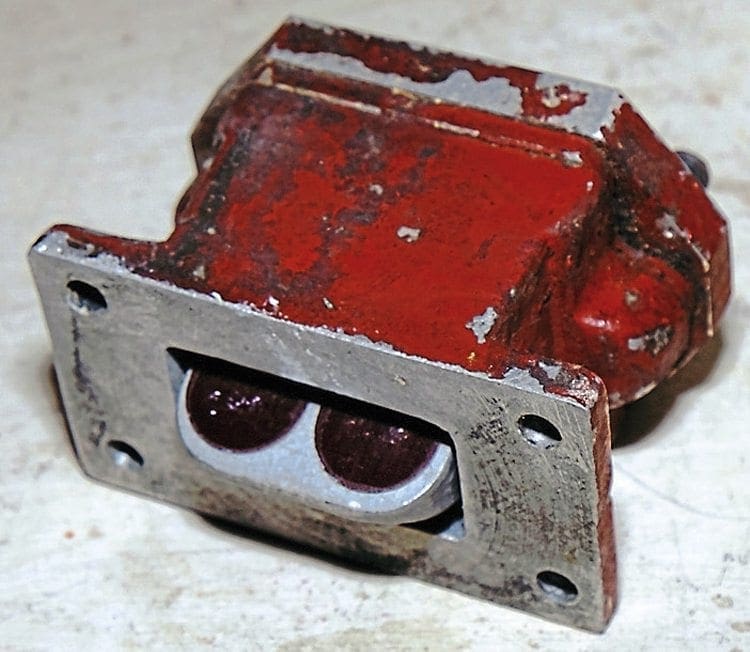

The reed block would have to be offset slightly and sit just to the right of the bump stop and was to be made from aluminium. Having created a mould he experimented using high grade molten aluminium to create the casting. However after cooling down the shrinkage meant it didn’t fit correctly. After several failed attempts a new way of making the casting was tried, this time using a composite resin and fibreglass. There was an airtight fit and the resin was strong enough to take the deep threads which were needed to bolt the reed block securely. All that was now required was to exactly shape the inlet port and the passageway for the reed valve. The reed block, taken from a marine engine, had four reed valves in total. Once in place a manifold could be made to fit the 30mm Dellorto carb. With the original inlet manifold on the cylinder sealed off, the reed valve conversion was completed and had enough clearance once the engine was fitted in to the frame.

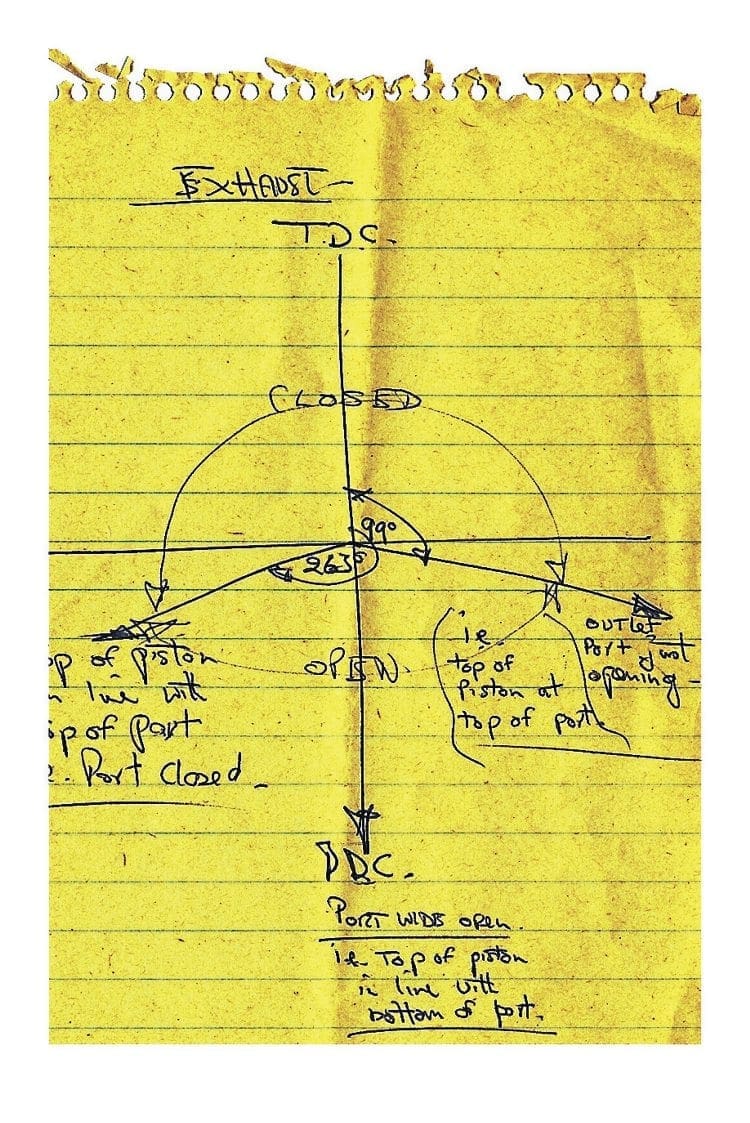

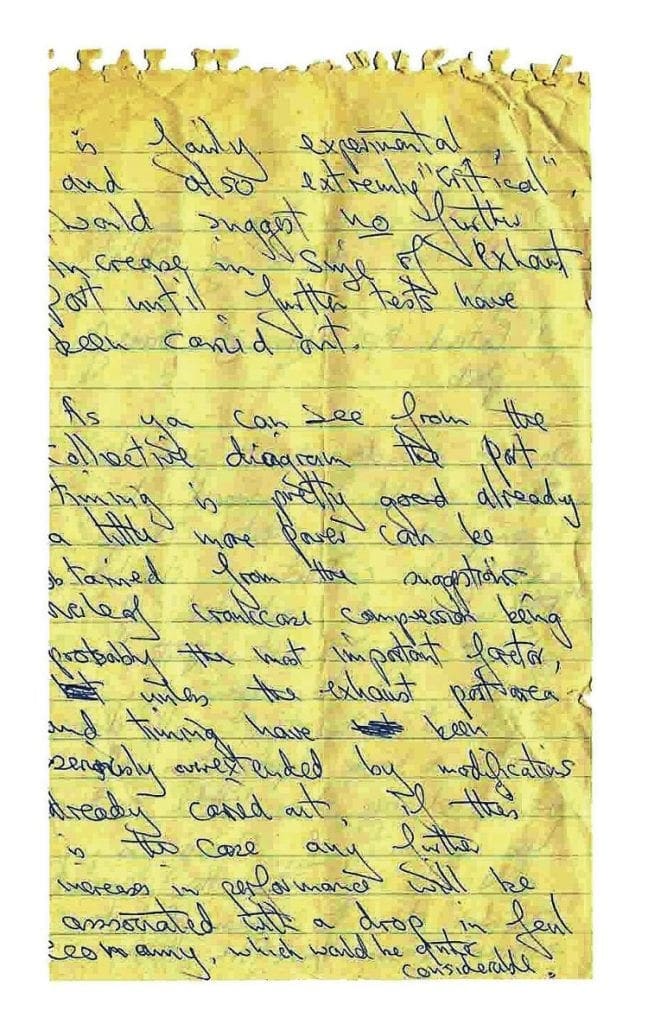

Not content with this unique modification, Steve set about building a new expansion chamber worthy of the project. By now having studied and worked on many types of two-stroke engine Steve was able to come up with a design that would suit the engine’s characteristics. Once drawn on paper the design was sent to Campbell Geometrics who produced the pipe to his exact specification. Once made, several extra sections were cut and welded in to allow the pipe to follow the contours of the engine and frame. With other modifications to the cylinder head and ignition the engine was completed and ready to try out for the first time.

Testing times

With the engine bolted back in to the frame and ready to roll Steve set about taking it out for its first test run. There was an immediate gain in performance of around 10% even though the engine was suffering from fuel starvation. Re-jetting the engine and smoothing off the front of the throttle slide to aid flow helped improve performance even further and show the real potential which this engine had. Not content with this power increase, Steve set the engine up to run on methanol. The compression was raised by switching to a 13:1 compression head and changing the firing point on the ignition. After the first run on the new setup it became clear there was still a fuel starvation problem which can be quite common on methanol burning engines. By drilling out the main jet to its limit, the problem was solved and Steve had no problems running on full throttle. The one problem he did have though was staying on the machine as the acceleration and speed were phenomenal. To this day Steve can still recall the moment in his mind realising all the hard work over several years had paid off to produce what he called such a powerful beast’.

The real acid test came when Steve and a couple of friends took the Lambretta to a local airfield to try it out. Racing over the quarter mile against a standard GP 200 Steve completed the distance while his friend had only covered an eighth of the distance – not only showing its superiority but also how much power the reed valve engine was kicking out. By this time it was mid-1974 and it was too late in the season to get started racing.

What could have been

By early 1975 Steve had got married, bought a house and was busy setting up a new business. With all this going on both the tuning and racing took a back seat. From time to time the Lambretta was subject to the odd blast up the local air strip but sadly that was all. Slowly but surely Steve’s busy life took over and the Lambretta along with all the hard years of tuning and testing was retired to the back of the garage. Despite having got this far developing and proving that not only could reed valve induction work on a Lambretta engine but that it would also significantly improve performance it was never actually raced. Just what could have been we will never know and just how much further it could have been developed.

One thing is for sure, Steve Saffin was well ahead of his time in two-stroke tuning and certainly in the Lambretta world. Having learned from those around him and having the foresight to see that you could take ideas from any type of two-stroke and adapt it to work on a Lambretta engine was pure genius. When it came to the tuning itself, methodically working out detailed diagrams and keeping a daily diary of how each staged progressed. As for the Lambretta itself, well Steve still owns it to this day albeit stripped down. Now retired and with more time on his hands the plan is to restore it to its former glory and who knows, maybe one day it will finally take to the track.

Words: Stu Owen