Having dressed numerous film and music video stars, it’s unsurprising that Roger Burton has decided to not only document his time in the business, but also the collection of attire he’s amassed along the way.

Rebel Threads is a book spanning the range of British youth subcultures from the war onwards and delving into the fashions which gave them their name. We caught up with the author, a former Midlands Mod, in among his racks of vintage clobber to talk Trevira, Toyah and Trojan…

Film director Julien Temple wrote the foreword — how did that come about?

I started working with Julien in ’82. I believe the first video I did with him was for The Beat’s Save it for Later. It’s funny because a lot of the clothes I used in the video were seen later in Absolute Beginners, which in a way was like one big music video, and now many of these clothes feature in Rebel Threads. Thanks to magazines like The Face, iD and Blitz there was a lot of interest in period fashion and in a sense, music videos became like the pages of a magazine, however there was a real shortage of good authentic clothing on the scene, so a lot of recycling from contemporary wardrobes took place. I have this fabulous original 40s American zoot suit that in ’81 I styled on Terry Hall from the Specials in Ghost Town. The suit was in so much demand, I also styled it on the Kinks’ Ray Davies in their 1983 music video Come Dancing. I styled countless music videos for Julien during the 80s and they were always on an epic scale, like mini feature films packed with characters in colourful street styles of the time. He was as fascinated by the then current youth culture as I was, so together we made a good team.

The collection began with some of your grandfather’s ties — did you think it would end up as large as it has?

I was fortunate in that my grandfather, and my uncle were quite stylish and they were both the right age to be into clothes in the 40s and 50s. So although neither of them were anywhere near my size, I did rather well raiding their wardrobes for period ties, and these ties formed the basis of my collection. They mostly had stylised prints such as lightning flashes or zig-zag patterns, sub Art Deco, similar to those seen in Brighton Rock, but there were also a few hand-painted abstract designs like those seen in American noir movies.

I have been a collector for as long as I can remember; as a kid it was everything from badges to exotic cigarette packets, but of course I had no idea in the 60s that my clothes collection would eventually turn into the serious and well-respected archive it has become. I only ever really collected stuff for my own pleasure so it was a real bonus when other people started to appreciate it and the great thing is because we only hire items from the collection, people can enjoy them for as long as they like, providing they are prepared to pay, but at the end of the day I always get them back.

How did you source the clothes at the beginning?

I first began to find 30s and 40s clothes at second hand stalls on Leicester market, also at jumble sales, and in junk shops, in and around the city, then eventually I discovered an army surplus store in the market place called Wakefields that had brand new old stock menswear that they would put outside the store whenever they had a sale. This was a great find as they had large quantities of stock that I would later sell to shops like Acme Attractions on the Kings Road in the 70s. As demand grew beyond my own needs I started to go to other towns like Birmingham where there was a large rag market.

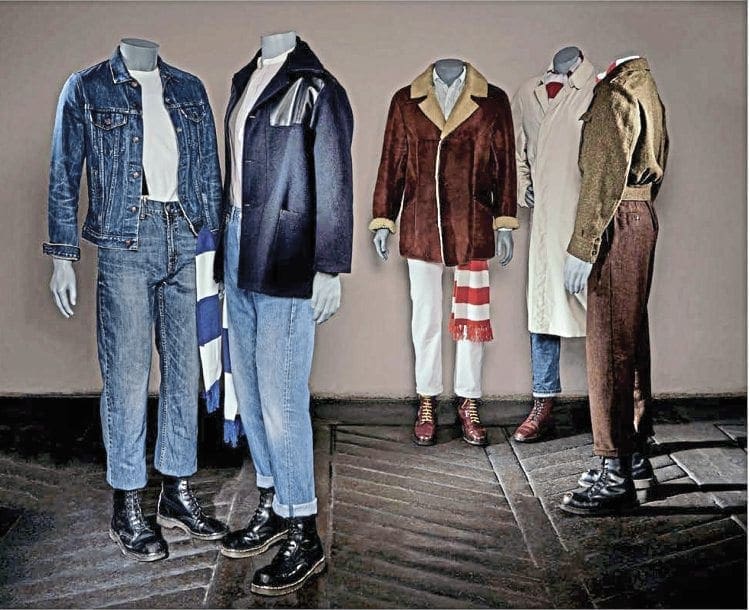

Was Quadrophenia the first big production you worked on? How did that come about? We originally got involved in a small way with supplying clothes for a movie called The Rutles in ’77 through the film’s costume designer. But Quadrophenia was really the first film production we were asked to supply in large quantities to. It came about by chance really, we happened to have a stall on Portobello Road market one Saturday in ’77, and this guy who was an art director on the movie. I happened to be passing by and noticed that we had a good selection of 60s suits and dresses for sale on the stall. My partner Rick Carter, also an ex-Mod, got talking to him about the project, and by Monday we had net with the film’s producers and secured a contract to supply authentic Mod clothes for the film, also both being ex-Mods we became consultants on the look of the clothes.

How involved were you with the film?

My role on the film was chiefly as a supplier and consultant, and although I met most of the actors during production I was only able to advise on their look unofficially as I was not part of the production team. Quadrophenia was a relatively low budget movie, and as was common practice at that time with low budget movies, the wardrobe supervisor took the place of a costume designer and covered both roles.

As a former Mod was authenticity always on your mind?

We were always trying to make sure that the clothes we supplied were not only authentic, but being worn in the correct way, by liaising with the wardrobe supervisor, however not being on set made it almost impossible to scrutinise, especially with other people supplying clothes too. One of the first things we were asked to supply were around 100 original M51 and M65 style parkas, but at that time there was some sort of EU regulation in force that they could not be sold to the public as issued to the military, so many of the hoods were separated from the parka shells, but we managed to locate a package of hoods in Europe and had to get them sewn back together. Also it was and still is almost impossible to find men’s suede coats from the 60s, and as these were an integral part of a Mod’s wardrobe we had some made up in different colours. However, the art director thought that the public would not believe that boys wore pink suede coats so he wouldn’t allow them to be seen in the film.

The book shows a lot of fondness for post-war Spivs and wide boys as the beginning of subculture and style.

I grew up in the 50s in a country village watching glamorous 30s and 40s black and white noir movies. I was particularly attracted to those shot in England with glamorous clothes that were so American influenced. Brown gabardine suits, two-tone suede brogue shoes, novelty ties, pencil skirts, leopard print swing coat and matching hats.

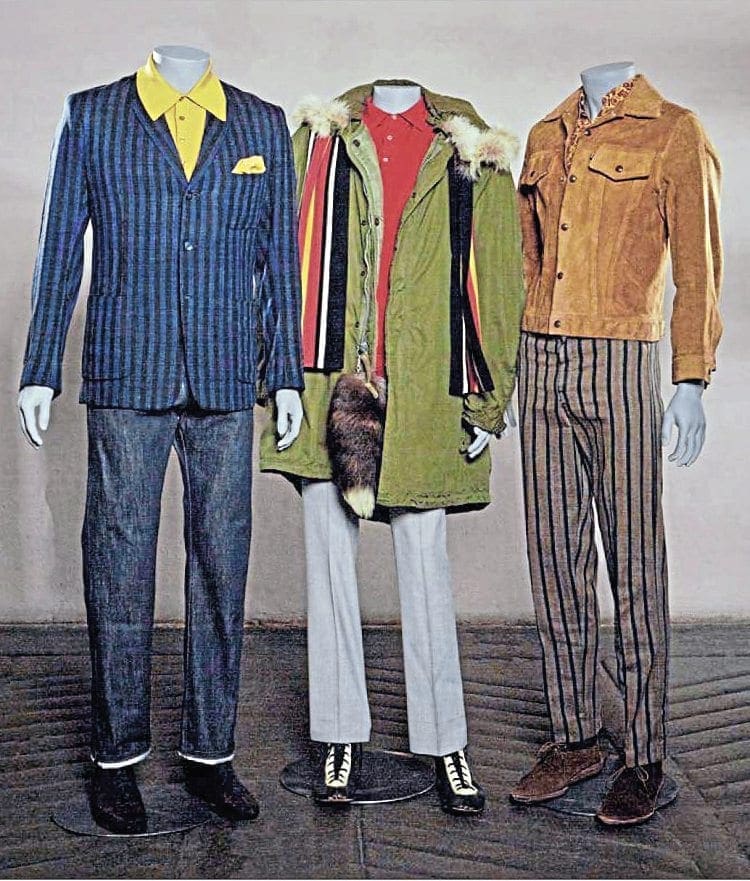

You mention how Prince of Wales check and houndstooth found favour with the Teds after that?

During the early 50s, tailors who were making drape suits for young Teds in East End London were quite keen to emulate the upper class Edwardian suits being seen around West End gentleman’s clubs, and they began using fabrics such as houndstooth and Glenurquhart check as a pastiche of the look. This distinctive check had been made popular by the Prince of Wales some years earlier, in fact so much so that the check would almost exclusively become known as Prince of Wales check. After falling out of favour with the Teds the fabric became popular again with the mid 60s Dandies, and then in the early 70s it was adopted by suedeheads, again aping upper class styles.

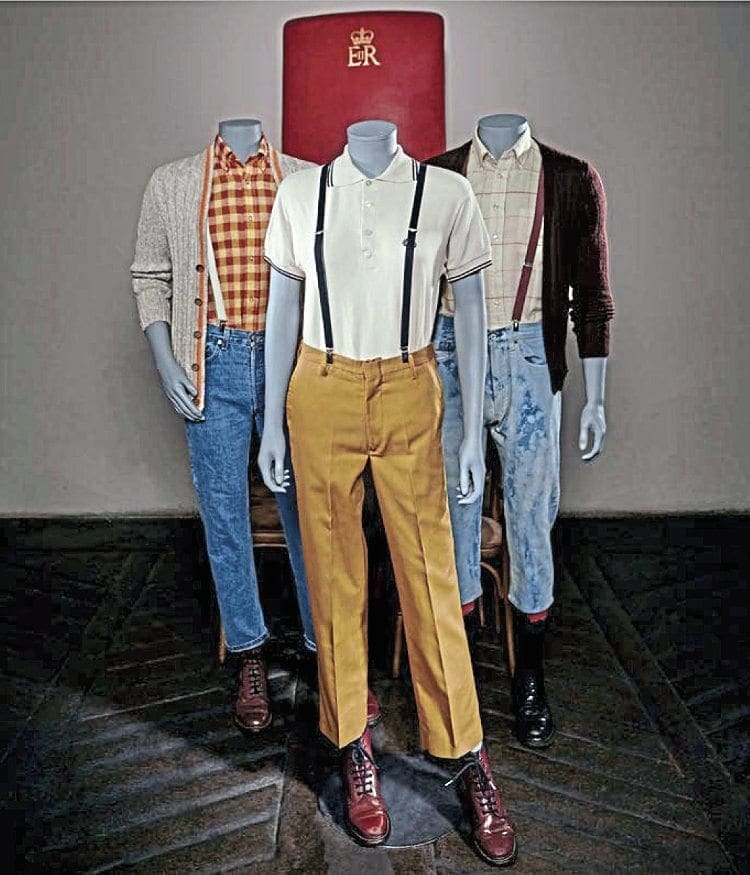

Likewise, the book gives an affectionate and balanced look at skinhead, but has them wearing braces over Fred Perrys and also in wartime clothes?

I remember seeing kids in Leicester in the late 60s who were sporting the Skinhead haircut and wearing variations of Second World War army jackets and trousers, collarless grandad shirts, and donkey jackets, probably because they thought they were a cool anti-fashion working class uniform and good way of making a statement, plus the fact they could be found quite cheaply in surplus stores around the country. Of course, it could have just been a regional thing, as with braces being worn over Fred Perrys. As I said at the beginning of the book, the styling of the outfits is of course subjective and purely my own personal point of view, and I respect the fact that certain sub-cultures or movements in other countries, towns or even local areas will have worn their clothes in a different way.

Interview: Andrew Stevens

Photographs: James Lyndsay