There’s a number of ways to clean off years of road grime and thanks to BAW Coatings, Scootering magazine can now offer another — powdered gemstones.

In the mid-1990s, when restoration was first becoming popular, I bought an LI with the intention of returning it to former glory. I started by sending the engine block to the local blasters for cleaning, unfortunately it returned looking like a lump of coral! We’ve come a long way since then both in knowledge and techniques. While vapour and soda blasting routinely provide less destructive methods of removing paint and oxidisation, powdered gemstones have long been used as an abrasive in high-end commercial applications. This process offers many advantages but until now the cost has been beyond the reach of most scooterists. Fortunately Chris Akid, co-director of Sheffield based BAW Coatings, is a long standing enthusiast and wants to see the technology applied to more scooter restorations.

“The problem with most blast cleaning materials is that they’re a compromise” began Chris. “Iron particles are effective but there’s a real risk of deforming panels. Methods such as vapour blasting are much gentler but don’t always achieve the desired result. We use powdered garnet as it’s strong enough to get the job done but also gentle enough to avoid damage.”

Formed in 2014, by Chris and business partner Blaine Wass, Sheffield based BAW Coatings provides cleaning and coating services to the nuclear power, aerospace and heritage industries. Its blast rooms can accommodate everything from small valve bodies to structures weighing up to 140 tonnes but its smaller projects that fire Chris’s enthusiasm. “I take great pride in being part of some incredible civil engineering projects, but working on a scooter is helping someone’s dream come to life. There’s nothing more satisfying than that.”

Jewel in the crown

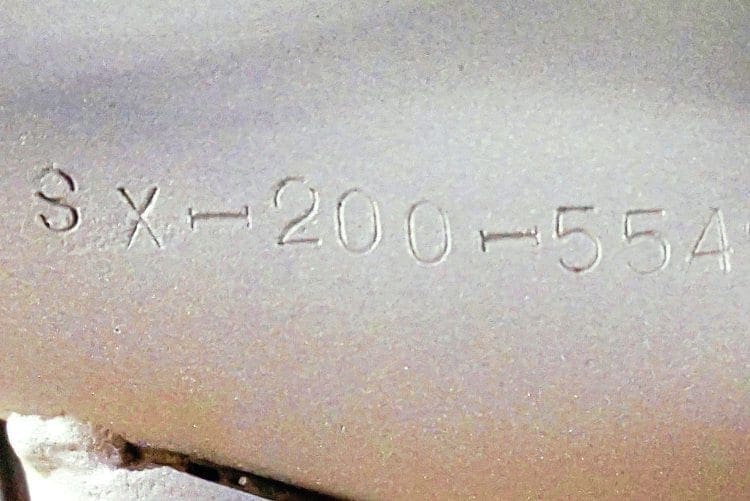

Like most scooterists I’ve endured years of hype around products and services, many of which have proven to be ‘over optimistic’. Expecting some cynicism Chris made a simple offer: “Bring a scooter and I’ll show you what we can do.” So, armed with a stripped down Jet 200, I paid Chris a visit. His initial reaction was disappointment: “The engine’s stripped!” Surprisingly the garnet process is so gentle that a degreased engine only requires the inlet/outlet ports sealing and it’ll go straight into the blast room. “It won’t affect gaskets, exposed oil seals or engine mounts,” explained Chris. “There’s also no need to mask off threads or bearing faces.”

After 20 minutes, Scott opens the blast room door to reveal what looks like a brand new engine. The transformation’s astounding and ‘as advertised’ the engine rubbers are unharmed. Chris smiles and confesses there’s nothing new to the process: “My brother’s a jeweler; this is how they clean gold. We’ve just scaled up the process.”

Somewhat skeptically, I handed the engine case to Scott, who was to do all the hard work. “This is a two-part process,” explained Chris. “The garnet’s like T-Cut, it restores the surface but leaves alloy very susceptible to handling marks. To prevent that we use micro-glass beads which seal the surface, just as car wax seals paint. As the process is non-metallic no deposits of iron are left on the surface. These can ultimately rust and ruin the finish, it’s ideal for engine cases and also one of the few methods that can be used to blast stainless steel.”

Limitations and potential

Next into the bay were the frame and panels. Cleaning cast metal is one thing but removing paint from pressed steel without deformation is another matter. The Jet 200 had been chosen as our test subject because the panels had come from various sources. Between them and the frame we were testing the process against everything from factory paint to brush applied Dulux, a selection that quickly exposed the process’s one weakness. As Scott began to work his magic Chris turned from the viewing panel and said: “There’s a lot of filler in there. That’ll need something more abrasive than garnet.” Although visibly disappointed, Chris had one more trick up his sleeve. Handing the tool box lid back to Scott, Chris asked him to finish it off with glass beads. “We don’t use glass on metal that’s going to be painted, it leaves the surface too smooth for the paint to key.” A few minutes later the lid returned polished, not to a mirror finish, but it certainly wouldn’t look out of place in a kitchen. “I’ve got a project in mind,” Chris says enigmatically, “a bare metal Vespa so clean it’ll look like it’s just come out of a press. I just need to fine tune the clear coat…”

GARNET, JEWELLERY TO JET 200

Found across the world, garnets are a group of silica materials that have been used for millennia as gemstones and abrasives. Although it’s found in a variety of colours the most well-known stones are deep red. These were particularly valued during the Roman period and examples inlaid into gold have been found by archaeologists from England to the Black Sea.

Because of its availability and consistent quality, garnet is a popular abrasive used in high end applications such as cabinet making and jewellery. The most common sources of abrasive garnet are from India and Australia where it can be found along wide expanses of the coast, having been naturally ground into a fine powder over millions of years.

For further information contact BAW on 075391 14013 or [email protected]

Words & Photographs: Stan