As our ‘painting by numbers’ series comes to a close, we finally take a look at airbrushing. Parts 1-6 (see back issues) have covered sandblast, primer and prep, paint, masking for multiple colours, pearls, flakes and candies. After a short break, we will be coming back in a couple of editions with a look at an amateur/home paint job using the lessons learnt, plus a look at rattle-can paint jobs, as well as a few alternatives to paint.

As I’m sure most of you know, airbrushing is the method of applying more detailed art works to existing paintjobs. Airbrushing can be considered the art of drawing with paint. Airbrushes are available in many types and configurations, with a large range of prices attached. Don’t make the mistake of thinking that an expensive one will automatically give better results. Jonno from Colour Worx in Scunthorpe, the artist who has assisted with this article, prefers to use a cheap £30 gun for most work, rather than the expensive one he keeps at home. It’s the type he’s used for many years and so is more experienced and comfortable with it. That said, there is nothing wrong with a more pricey brush. It’s just a matter of practising until you’re confident that you’ll get the desired results rather than of having the best kit available.

Talented enough?

Anyone can have a go at airbrushing, and the level at which you can ‘dip your toe in the water’ varies hugely. In talented hands, an airbrush can give incredibly realistic finishes but, as with anything, it’s all about practise. Someone who has a natural talent for art or drawing for example is probably more likely to have a natural talent for airbrushing too. One real tell-tale point of a good airbrush artist is the ability to accurately recreate faces.

If you look at any good piece of airbrushing on a scooter which involves portraits and faces, you’ll notice how accurate the likeness is. Some of the poorer artworks I’ve seen bear no resemblance to the intended portrait at all. For those who are not so good at portraits, or even at art itself, great results are still possible via the use of stencils and more simple designs. Our guide should illustrate this point perfectly.

What kind of paint is used?

Generally speaking, there are two kinds of paint in use, water based and solvent based. Although water based is naturally more environmentally friendly, it can take a long time to dry in comparison to the 30 minutes or so that a solvent base will take. As a result, most artists tend to lean towards solvent based paints, and these are what we will be looking at in this article. Almost any colour under the sun is available too, but unless you specifically need to match to an existing paint scheme, then it’s easy and cheap to base your work on a handful of plain colours and mix them to achieve colours required. Mixing charts are available to give advice on how to do this. Most paints come pre-mixed to a certain viscosity, but nearly all artists like to add solvent to make it easier to spray, the level is a matter of personal preference. Thicker paint obviously gives a more solid colour, with more solvent helping to get a lighter coating. Don’t add too much though as the paint will become watery and unpredictable. Try slowly diluting the mix as you spray onto a practice panel until you are happy with the results given, making notes as you go along.

Preparation

The paint you are spraying needs a clean surface to stick to which has been lightly ‘keyed’ using wet and dry sandpaper. 2000 grit is around the level needed, anything coarser could leave marks. Clean off with a tac cloth and you’re good to go. Apply the basecoat colour for the background to the image, allow to dry and then re-key lightly and clean off again.

Masking

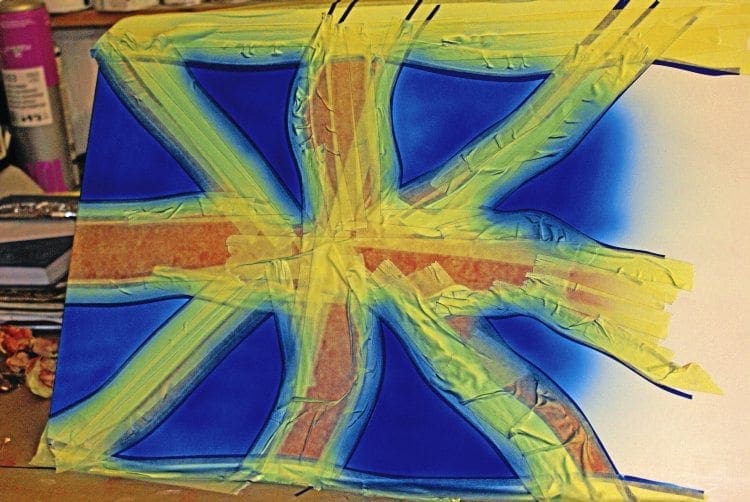

Jonno may only use a cheap airbrush in his work, but he insists that it’s worth spending money on good quality masking tape. Cover the area where the design will be applied, making sure that there are no gaps where overspray could get through. Draw your design, correcting where necessary, and then use a craft knife to remove the areas which are to be sprayed. It’s good technique to work from the largest amount of colour to the smallest in most designs, but there are times when this isn’t possible. Our simple design — the Union Flag — allows this to work here.

Spraying

Before going anywhere near the piece that you’re planning on spraying, take some time to get used to the airbrush, paint and air pressure. Make a few passes to see how they cover a practice area. Experiment with freehand lines and curves. Try to avoid runs and splatters, changing the consistency of the paint if needed. As with any paint application, consistency is the key. Try to keep your hand parallel to the piece when spraying. Instead of swinging it from side to side just using your forearm, try moving your whole body sideways while holding the gun steady. A 0.2mm gun is around the size needed for bulk colour on designs. Apply a light coat first to get a feel for how it will cover, as not all colours behave the same way. Once you’re happy with the colour applied, clean the airbrush and wait for the paint to cure, before re-masking for the next colour to be applied. The same methods should be followed and, if need be, a third or more large area of colour can be added.

At this point, before you get into the fine detail of the piece, Jonno recommends a coat or two of lacquer or intercoat to protect the base. This gives two advantages — firstly, it protects the piece from accidental damage. Secondly, it allows the artist to remove any areas of detail that he’s not happy with without damaging the base paint. He suggests that this should be done when you are able to leave the work for at least six hours at room temperature to cure properly. Obviously, overnight is ideal, and the longer the better. No need to get carried away with the amount of coats, one or two is sufficient.

Fine detailing

Once you’re happy with the basic design, then it’s time to get busy bringing it to life. For this, a narrower airbrush is used, in this case a 0.05mm needle is used. Again, get a feel for paint and pressure before you start.

Flat the protective layer back, again using 2000 grit wet and dry, then wipe clean with a tac rag to remove any residual debris which could ruin the paint.

Before you go any further, have a think about what detail you need to apply, and how it would fit best. In the design that we’ve used, a rippling and tattered Union Flag, it was obvious that there would be peaks and troughs in the image, and that the tips where it was torn would need to look dirty and distressed, and that a drop shadow would be needed to ‘lift’ the image off the panel.

To get the look ‘right’, the artist needs to consider where the light source would be to get consistency, it would look amateurish if shadows were to appear on both sides of a raised fold, and so a single angle needs to be decided on. With this in mind, the main image is masked off as in the earlier stages and the drop shadow applied. Once you’re happy with that, it’s time to move on to the final stages.

Shadows of the creases are gently applied first. Depending on the severity of the fold, either a sharp or soft edge is used. A soft edge is achieved by spraying straight onto the picture, while a sharp edge is best achieved by using a hand held mask that has been cut to an appropriate shape. This allows for heavier paint coverage if needed, without the fear of a soft edge appearing. These give an apparent depth to the folds. As these are added, the picture will start to take on a slight 3D effect as the eye tells the brain that the darker areas sit below the main image. To finish the effect, lighter coloured highlights using white paint are then sprayed on the corresponding peaks. It’s easy to get carried away doing this, so keep stopping, looking at the shape of the overall piece, and then adding only as much as is needed to complete the illusion.

Knowing when the picture is finished is key. Don’t be afraid to walk away a few times, coming back to add more if needed, or even to gently remove anything you feel that you’ve got carried away with. Finally, apply a couple of coats of lacquer, turn the lights out, and call it a day!

Words & Photographs: Nik

Thanks to Jonno at Colour Worx Bike And Scooter Paintshop at Scunthorpe for his invaluable assistance with this article.