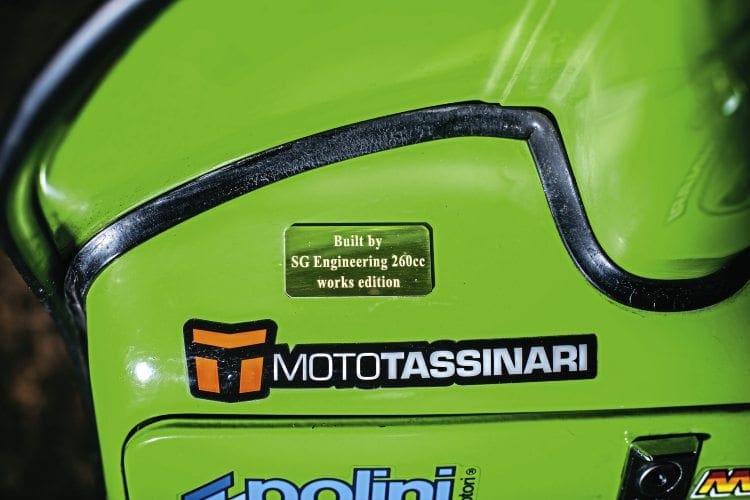

Stuart Gentry is about to put a mark on the scootering map with the introduction of his 261cc P-range, a Vespa with the potential to hit the magical 100mph in real world conditions.

30mph-90mph+ in top gear

Started only nine years ago by someone with no historic connection to the scooter scene, SG Engineering has become one of the best kept secrets of the industry, with their 230cc engine developing a reputation as one of the best touring lumps around. Owner Stuart Gentry gave Scootering an exclusive look at his new Vespa 261cc engine, with a hint of more to come; a machine that’s already been clocked via GPS at a pretty astounding 94mph. Sadly it started to suffer fuel starvation at that speed, meaning that he couldn’t ride it flat out for extended periods. So although he’s not managed it yet, the current performance is a good indicator that Stuart is going to hit that magical milestone sometime soon. An important thing to remember here is that the scooter isn’t a peaky rev-monster.

Stuart says that he designs engines to roll on from 30mph in top, pulling all the way to top speed, even with a pillion on board. While this may not make for a screaming quarter mile machine, it does allow for a very rideable scooter for day to day and distance work. A quick chat with the somewhat modest tuner behind these engines was definitely needed.

A word with the man

“I’ve no background in scooters, I come from an engineering background though, working as a development engineer in plastics until I was made redundant, designing castings and the like. I’ve never minded getting my hands dirty though, and used to help a mate who was into scooters keep his running. It just developed from there.

“Around 25 years ago I used to go watching motorbike racing, and would spend as much time as possible in the pit lane watching tuners doing their thing, and learning from what I saw.

“From there, I’d bring bits of knowledge home with me and apply it to scooters that I’d be playing with for friends. Setting up the carb properly is very important, it’s a major cause of so many problems, and something I learned to do. Even though I’ve now got a dyno, I tend to do my initial set-up by ear, and results on the rolling road show that I’m generally pretty close, and I’ve had scooters coming back to me after a few years, ones that I built before the dyno, that are still pretty much on the mark.

“It was a bit of a running joke that people would ask how fast a scooter I’d built would make it home from Weston-super-Mare in one piece instead of coming home on the back of the AA van!

“One day I was offered a P200 in part payment for some work I’d done; it seemed a reasonable deal so took it. This is the scooter I still ride now, a Mk1 P200, and it was the test bed for the 230 straight from the off. I’d had the engine spec drawn up for a while, but I’d never been in a position to build it, so it seemed like the ideal time to finally do it. I’ve always thought that ‘little is more’ when it comes to tuning engines though. Make a change, prove it, and move on to the next. Obviously there are always the occasional snags, but in recent years they’ve become much less common, and you have to learn from them.

“Scooters can be finicky, so the secret is to allow for the weak points while making them as powerful as possible. One thing I do, and it’s something that seems to have recently become popular, is to pressure test for leaks. It always seems to be the engines that you think can’t possibly have a leak that do!

“The biggest difference in the way I like to build engines is with the way power is produced. Most tuners seem to build machines that scream up to top speed rapidly, giving a very narrow and peaky chart on the dyno. In comparison, mine have more of a diesel type power curve, one that’s very broad and flat, allowing for a low rev roll on to pull away, something I think makes for a much more relaxed riding. Bear in mind that you’re riding something with awful aerodynamics, so grunt is more important than outright revs in my opinion! Up-gear the engine and you’re away, as it will happily pull higher ratios due to the torque figures being in the region of 20lb-ft on the 230.

“I had one of my customers from Skegness tell me that he’d been leaving TS1s behind going up hills to Scarborough. He was still in top when the Lambrettas had dropped to third or even secong, so this suggests that I’m heading in the right direction for road scooters.

“Don’t get the idea that I’ve come up with any new ideas though, I haven’t. All I think I’ve done is to take old ideas and use them better than they have been historically, but I wanted to do things that people have always said you can’t do to a Vespa. Although I’ll work on Lambrettas, the new generation of P-range casings and cylinders have largely levelled the playing field with them, but at a much reduced price, meaning that the 260 is a high speed mile muncher that can be built at a better price than the competition. Although it’s not hit 100mph yet, I’m convinced it will do, and if that fails… well, let’s just say there is still more to come!”

261CC TECH SPEC

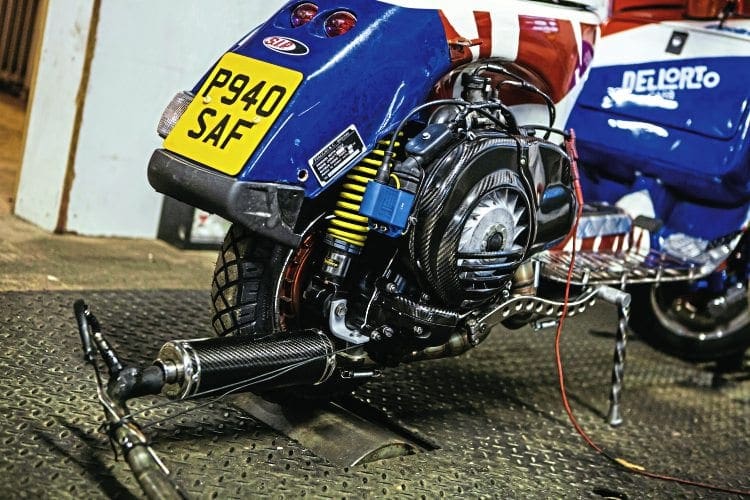

Engine cases: Pinasco.

Cylinder Kit: Quattrini 232.

Crank: Kingwelle 64mm.

Carb: Mikuni TMX 38mm.

Clutch & Gearbox: DRT.

Ignition: Standard Piaggio, set to 17 BTDC, flywheel lightened on lathe.

Pipe: Canonized road exhaust.

Claimed power: 40bho and 30lb-ft.

Words: Nik

Photography: Gary Chapman

BIG THUMPER TECH SPEC – A WORD WITH THE EDITIOR

Having heard good things about Stu and the scooters he was working on, as always, I wanted to get to the nitty gritty of what he was doing with them in technical terms. We had an initial conversation about his history in engineering, how he moved into the world of scooters, and it became obvious that Stu hadn’t reinvented the wheel… more like, stripped it down, taken a long look, had a bit of a think, bought some quality spokes, and rebuilt it to engineering standards, with the consumer’s end use in mind. It would seem that this ethos has been the foundation of how he approaches scooters, and it certainly seems to be working for him.

Not from round these parts are you?

It’s always interesting, to me anyway, when someone outside of the scootering fraternity delves into the scooter tuning/building scene… as what has often been overlooked for many years can become very obvious when someone else points it out. Or conversely, ideas which have become entrenched in scootering folklore (we must use this part like this, and that part like that) are not utilised, because the person executing the build has no concept of them. The only caveat to all this, is that scooters can be very unique in their set-ups. There are many nuances to each scooter and the individual component for them on the market, how they interact with other components, and scooters owners tend to learn this stuff inside out: this pipe works well on this kit, or info on routing fuel pipes and header pressures on Vespa petrol tanks… and so on. In these instances, knowledge is something which comes in very useful. But it doesn’t take long to learn many of these things, especially as an owner/rider/tuner.

By his own admission, Stu has hit a few snags… but more importantly, his analytical engineering background has proven its worth, and you can see this in his interview quote: “Make a change, prove it, and move on to the next. Obviously there are always the occasional snags, but in recent years they’ve become much less common, and you have to learn from them”. That to me says two things: 1) His tuning steps are methodical and logical. 2) His errors are noted and addressed. That’s important.

What’s going on inside?

So the big beast, all 261cc of it… what has Stu done to get the rip-snorting performance to this level? Well, quite simply, he has made a good selection of components, which work well together as a complete package, and assembled them to engineering standards. He is using Pinasco casing to overcome the well-known problem of standard P-range Vespa casings cracking like the San Andreas fault line, a Quattrini 232 kit as the powerhouse, a Kingwelle 64mm crank to get the big-cc capacity, and a DRT clutch and gearbox to distribute the torque. Top this off with a standard Piaggio ignition (K.I.S.S.) which has had the standard flywheel machined and set to 17 degrees BTDC, a 38mm TMX and a relatively unknown German pipe brand… and there you have it, quality components put together correctly. Pressure tested, dyno tested, road tested… in that order. By his own admission, it’s still in development, and from what he told me the port timings still need a little tweak in order to get the best from the setup, but it sounds like he’s on the right track.

The power?

Well, according to Stu, even when riding ‘off pipe’ (this means before the main power band kicks in) on his dyno it is reaching 20bhp at around 4500rpm, the main surge of power starts just before 5500rpm and it builds until it peaks at 40bhp around 7500rpm and hold the peak almost flat until 9000rpm, before finally dropping off! In his own words “I try to produce engines with broad power bands, which will pull gearing”.

Well it certainly appears that he is managing it. Already GPS’d at 94mph, once the fuel pump issues is resolved, 100mph could well be achievable. Stu remarked: “I’ve done all the calculations and wind drag models on the computer, the ton shouldn’t be a problem once I’ve got the fuelling sorted.” While the 261 is his own play thing, the 232cc engines which he produces for customers are knocking out 20lb-ft of torque all day long, and seem to make the perfect mile munchers. It’s good that he is pushing the boundaries and developing the crazy stuff for himself, and then utilising the info to provide powerful, reliable and more sedate models on the road for his customers. If and when he cracks the ton, we will let you know.

Dan