While it’s good to achieve high bhp from the cylinder, getting all the power to the rear wheel is often overlooked…

Ever since the first Lambretta engine was tuned the emphasis has always been on trying to create as much power as possible. That’s fine but just because an engine has a large amount of power doesn’t mean to say its full potential is being used. There are many reasons for this being the case, from the cylinder area where the power is created, through the drive train, finally to the gearbox. To analyse exactly what’s going on, it’s worth looking in more detail at these three areas separately.

Top end

It doesn’t matter whether you have a mild tune of say around 18bhp or something greater, perhaps 30+ bhp, the principle is the same when it comes to utilizing the power you have. The first things to look at are the bearings, because anywhere there is movement… there is friction. Friction on the bearings, even in small amounts, will be holding back some of the power being created. Each bearing should be creating the minimum friction possible.

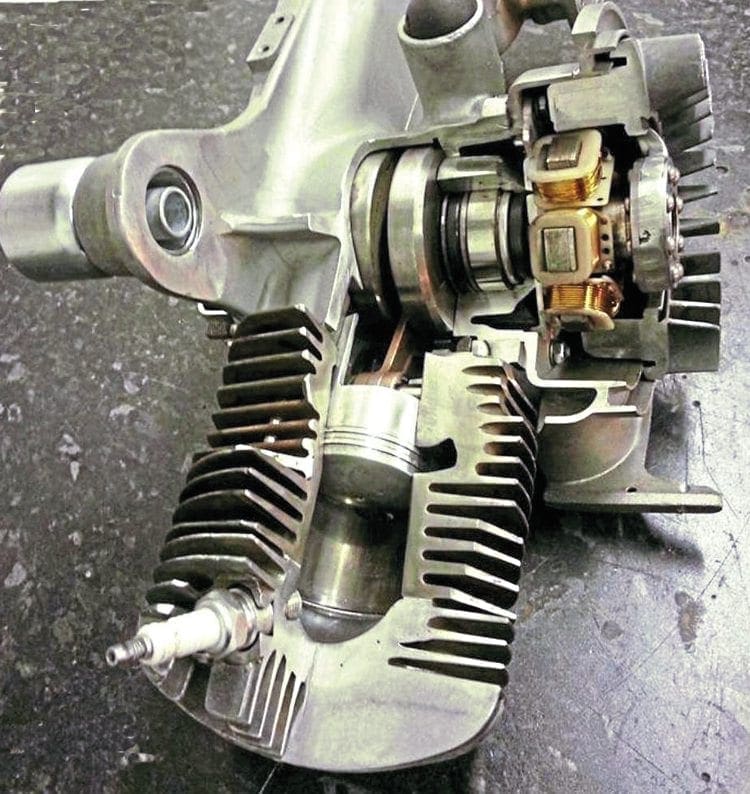

Taking the main bearing that supports the crank first, it is possible to use a ceramic version rather than the traditional steel ball bearing type, which has significantly less friction. On the mag side, the choice is limited as it has to be a cylindrical roller bearing to take the load of the flywheel on the end of the crankshaft. What is important is the quality to make sure the tolerances are machined to perfection. A poor quality mag side bearing will heat up quicker and produce far more friction.

Next are the crank-rod bearings themselves which again are vitally important. It must be presumed the con rod you are using will be of superior quality and also the bearing for it. As the majority of performance crankshafts use Japanese con rods then the bearing will be good enough. Using a cheaper crank will usually mean a lesser quality bearing, again not performing as well at higher rpm. It can be a minefield out there when looking for the right crank but if possible always go down the Japanese con rod and bearing route. It’s the same for the small end bearing; always use a genuine Japanese one which will have far better rolling qualities. The better the rolling resistance on all four bearings means less friction, certainly at high rpm.

Oil seals are another area where friction can occur at the top end. With three in total they grip the moving circumference of the crankshaft and though you wouldn’t think so, they are also creating resistance. There is no need to reiterate the importance of the quality of the seals you use, to make sure they do the job properly. If possible only use single lip rather than double lip when looking for max performance. The second lip is to stop dust which in theory isn’t required in the engine.

Next in the top end section is the crank and flywheel. The crank itself must be as true as it possibly can be. Even if it is slightly out of line then it can have a two-fold effect. Firstly heavy vibration and secondly wear on the bearing surfaces again causing friction. Not only should the crankshaft be perfectly true, but also the casings should be checked for their trueness before fitting to make sure both bearing seats align perfectly.

As for the flywheel, that needs to be the optimum weight. For general road use what is called the ‘intermediate weight’ of 1.8kg is fine, but to get the optimum weight for acceleration (while still providing enough inertia) 1.3kg is deemed to be the best choice for a road going Lambretta. Going under that can reduce the inertia too much, resulting in a drop in torque which, for example, is required when accelerating from a standing start (drag racers be aware). The other problem with some of the flywheels currently available is their build quality, especially when it comes to machining and tolerances. Make sure you get the flywheel fully checked and machined perfectly.

The last top-end item to look at is the lubrication of the components, which is governed by the type of oil you use. The idea of the oil is to coat all parts evenly and ensure that no friction or heat build-up occurs. Of course, you also need oil in the top end, to lubricate and stop it seizing, and the better quality the oil… the better its qualities of preventing this happening. Quite often owners spend thousands on a Lambretta engine but then seek the cheapest two-stroke oil to put in, which does not make sense. Looking at a JASO rating on the back of an oil container is not the best way to compare oils. The JASO rating predominantly deals with the detergent levels and clean burning properties to meet government guidelines; it’s not a gauge of lubricity.

The debate over whether to use synthetic or castor-based oils is another one which has gone on for years, and everyone has a different opinion on it. Synthetic oils are expensive and put a lot of owners off for this one reason, but synthetic oils also have additives which help the molecules adhere better to the surface and create a light even coating of protection. Certainly in a race engine, or one that revs high, this quality is vitally important as it continues to do its job properly under high-load conditions. The argument continues when it comes to lower revving engines and whether expensive oils are actually needed. With so many opinions out there it is best to do your own research into the subject and speak to those out there using highly tuned Lambretta engines whether on the track or road before deciding.

Regardless of which one is right, the main thing is to get the mixture correct. Never fill up your tank and just tip some oil in thinking ‘that’s near enough’. Get a measuring jug and do it accurately. Too little oil and of course it is possible to seize the piston or wear the big end and small end bearings. Too much can also cause trouble as deposits will remain in the top end area causing such problems as the piston rings to gum up. Also, remember the more oil in the mixture the less fuel that is entering, thus causing the petrol mixture to weaken which in turn can have dire consequences.

Research all of what has been described as far as you can for either components or services you can use. Remember it doesn’t necessarily have to be a scooter-related business that could supply the answer to your requirements.

Transmission and drive train

The job the transmission part of the drive train does is to get the power from the top end to the gearbox and rear wheel. This is the area where power loss is at its greatest. According to industry figures, it is possible to lose up to 15% of the power created at the top end through the transmission. This figure can vary between engine types and is probably slightly on the lesser side in a Lambretta engine. The main reason for this it that doesn’t have so many working components to go through — for example a differential etc. Even so, there are things you can do to make the power delivery through the transmission more efficient.

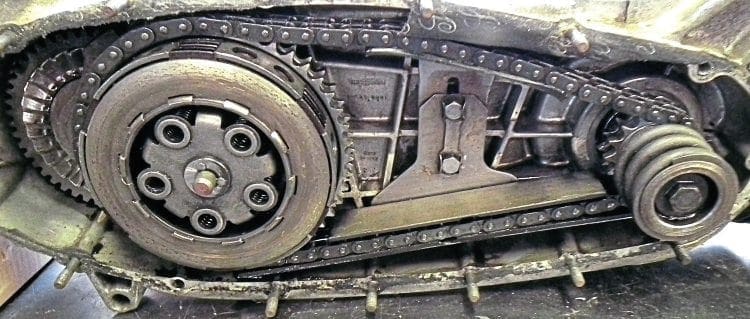

Starting at the crankshaft end of the drive sleeve, make sure it is in perfect condition. Check it is free from wear and any pitting on the sprocket surface which can happen on high bhp engines. Then check the sprocket itself, which not only must be free of wear on its running surface but also on the teeth. A point to note is to be careful buying a new one as some of the far eastern ones can be somewhat out of shape! Buy the best type possible and spin it to check it is perfectly in line. Being out of line will cause power loss and wear to the chain itself. The same goes for the sliding dog — get the best quality possible and make sure it and the sprocket spin freely on the drive sleeve. Next comes the tension spring which again must in perfect condition. An old or poor quality one may not hold enough tension when under strain, causing friction and wear between the sliding dog and the sprocket. If all components are perfect there should be no slipping of the cush-drive when the sprocket bolt is done up correctly even under high load.

Next in the transmission-line is the chain. This should be of the highest quality and regularly checked. Even though the only way to get certain sprocket combinations is by using a stretched chain. Try not to use one if possible. A stretched chain will be worn and pitting or wear may have occurred on the rollers which will cause friction. With the availability of push down chain tensioners, virtually every sprocket combination is now available using a new chain so there should be no excuse not to use one. If a chain is using a conventional push-up tensioner use a nylon type that offers less friction over the standard Innocenti factory one. At the same time, the bottom chain guide can be done away with, again reducing friction.

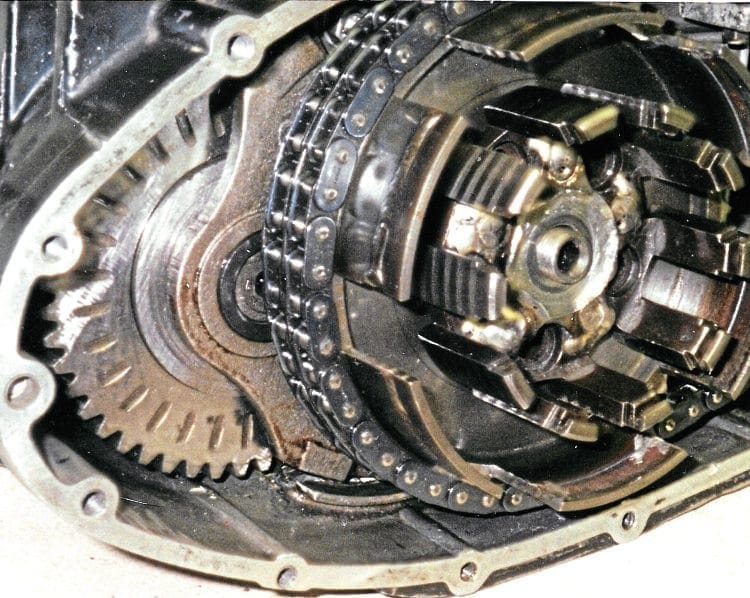

Now we are at the crown wheel and clutch area which is important to get right as this can be a big area of power loss. There are two main points to look at, firstly that the clutch is strong enough to cope with the power being put through it and secondly that both it and the crown wheel are as light as possible. This is a big weight mass in the train drive and removal of any weight on turning parts is much greater than general weight removal of the overall machine. Though the original Innocenti crown wheel is well made compared to the modern spoke type equivalent it is too heavy.

When it comes to the clutch itself there are a lot of options/brands, too many to go in to here, but if you only have a modest amount of power then there is no need to go to a much bigger and heavier six plate version; the extra weight isn’t warranted. Obviously, if you have a high powered engine a clutch that will cope with the power is essential. Look at all those on the market but bear two things in mind, how well it works and how heavy it is. This also includes the clutch spider, while it needs to be robust enough you don’t want it over-engineered and adding more mass than necessary. Overall, the correct balance of weight and strength is crucial.

The final part of this area is the crown wheel bearing. There are two choices – either the dual needle roller cage or the single brass bush. The needle roller bearing has more moving parts and the contact surface is far less across the entire surface compared to the brass bush. The general opinion is that there is less frictional force from the brass bush than that of the needle roller bearing and that it can take the weight load better certainly under strain. Seek out the best quality brass bush you can and don’t buy the cheapest as some of them can be a poor fit

Assuming you have all the components when everything is in place check the chain alignment. There are various aftermarket tools available to do this and you will require a dial gauge. If the chain is out of line then, in theory, you are forcing the chain in a different direction, not only causing wear but again causing friction and possible power loss.

Gearbox

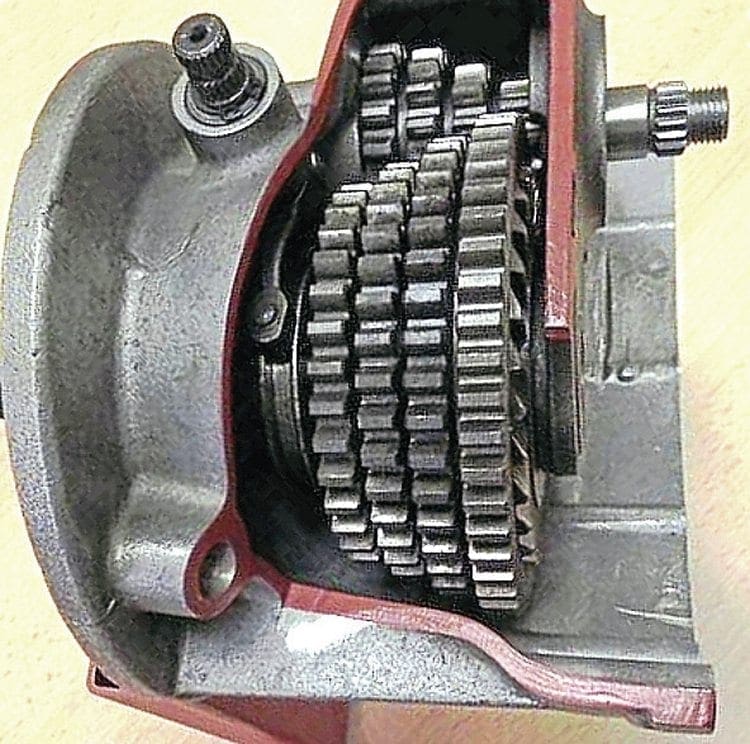

There are many options of which Lambretta gearbox to fit but all are interchangeable so follow the same fundamental principal in how efficient they are. There are four bearings involved — two on the cluster and two on the layshaft. All running surfaces and bearing housings should be free from any wear and if pitting has occurred should be changed immediately. This will cause the bearing to wear and lose efficiency. Alignment of the cluster and the loose gears should be perfect as if they are slightly out of line potentially the power is not being transmitted through them evenly. The loose gears sit and spin freely on the layshaft and there is a possibility of wear especially on the larger first gear cog (kick start gear). If there is wear on the layshaft don’t just replace that; the chances are there will be reciprocal wear on the gear track as well so they must also be replaced.

Shimming of the gearbox is of the utmost importance and while it doesn’t want to be too loose, being too tight will definitely lose power through the transmission. There are so many variances in casing, gearboxes, endplates, and layshafts that getting it just right can be a laborious process. Luckily there are far more shim sizes available these days so there should be no issue with getting the correct measurement. The correct shim gap should be between 0.07mm and 0.30mm but if you aim for 0.05mm that should give you good free movement with no chance of it being too tight, even when the engine is up to operating temperature.

Now the gears themselves, which are also a revolving mass, and if in any way they can be lightened, this will help with efficiency. The only real weight removing option is on the first gear cog by removing the kick start teeth. This is really only an option for a race or sprint engine as you will now have to bump start the machine, but it is a worthwhile exercise if this is the case.

In recent times there has been the introduction of the five-speed gearbox by several different manufacturers. This opens up a great wealth of gearing options and means there is less percentage jump between each gear. There are lots of things to consider — certainly the power delivery and how the top end is tuned. A tuner can now opt for a tighter power spread knowing he has five gears instead of four to use. One thing that must be considered is the extra weight of the turning mass. There will now be an extra gear cog spinning and also the cluster will be heavier. Again pulling away is where it will be noticed, rather than when the transmission is up and spinning. However, it may be possible that some of these new gearboxes are being made from a lighter material in which case that will offset the increase in weight slightly.

The final thing to look at and the one component that affects the whole of the transmission is the gearbox oil. Originally the Lambretta used ST90 which has a high viscosity. All of the transmission has to turn through this oil which creates drag — imagine you are walking through water which slows you down.

By using a much lighter grade of oil, around 75w, then the viscosity is much lower, thus eliminating drag. Never put too much oil into the transmission — half a litre is enough, the more you put in the more drag you create. Always remember to check your levels though

Summary

What has been described is ways of making your Lambretta engine as efficient as possible. Anything that can eliminate power loss in an engine is a worthwhile exercise. In a race or sprint engine, the smallest of increments in performance can mean the difference between winning and losing… especially when you are dealing with hundredths of a second across the line. On a road going Lambretta, you’re maximising the potential of what you have got.

Next month: Power to weight ratio

Words & photographs: Stu Owen