Lambrettas, life and engineering

He may not quite be Howard Hughes but the man behind the exotic scooter components of Gran Turismo is almost as hard to track down. Scootering speaks exclusively to Richard Taylor…

In the beginning

Gran Turismo has a reputation for innovative, high quality Lambretta tuning equipment, yet little is known about the company, its ethos or products under development. So it was with a mixture of excitement and nervousness I arrived at its Birmingham HQ. First impressions of Richard are that he is passionate, strongly believes in his product and has firm views on doing business, but how did it all start?

“Bizarrely I started in the arts,” he said. “While living in Germany I started racing 100cc go-karts, only a few little events here and there but I learned a lot about building two-stroke engines, particularly tuning and flowing, but only what was known at the time. I could go fast and have a laugh but was never in contention, I was lucky if the thing hadn’t disintegrated before the race’s end.

“After Germany I studied industrial design — art applied to consumer goods. That taught me about production processes and technical drawing. Scooters came later. First it was LDs and then I got a Series 2. I could build engines and restore a bike but I didn’t really get into tuning. At that time I was working with engineering contractors so I wasn’t scared by big machinery. The most exotic items were rocket engines, they were good fun. There’s nothing left when one of those fails!

“At this time I was hanging around with Derek Askil, and one day he said, ‘You’re a clever guy, why don’t you give us a kit for the Lambretta small block?’ At the time there was only the TS1 and so for some reason it struck a chord. I had experience in design, I understood two-strokes and I knew how to set up a business, including the financial side, so I thought why not?”

Of course we’ve all had those ‘bright idea’ conversations, usually towards closing time, but very few of them translate into reality. Richard, however, is made of sterner stuff.

Enter the 185

“The first thing to try and understand is the size of the market, and to identify what the customer wants. I started by asking around and looking at the TS1. The obvious things were that people didn’t like Nikasil coming away from the bore, and didn’t want to cut their battery tray off.

“There was also a limit to what people were prepared to pay so it narrowed down the envelope of what was acceptable. It was obvious that a reed-valve was needed, but the carb couldn’t come out at the right hand side. The challenge was fitting under the frame tube and the solution came out of karting. In virtually every 100cc kart engine there’s a low profile, wide, short-petal reed and that was low enough in order to fit underneath the frame tube. That’s why the kit works.

“Early on I was unsure if the kit was going to be iron or aluminium, but after visiting a few foundries the penny dropped that we needed iron, because of the problems and costs associated with aluminium casting. I used a chap called Keith Reynolds, who’s dead now. He was into go-karts and without him I’d still be messing round with the same old ideas.

“The other thing that helps is the piston size. As it’s smaller than the 200 we were able to configure things so it doesn’t catch the reed petal. We originally started with 175cc but it left us with the problem of pistons, the main choice being the heavy Meteors. The search for an alternative was no more technical than ‘there are loads of Japanese pistons let’s look at those’. Eventually I settled on the Yamaha 350LC piston. We added a finger down the boost port but that was it, they were the key things. A good piston with a lot of oversizes, the kart reed valve and packaging it to work with the carb on the left hand side. In all the time the kit’s been on the market I’ve never needed to revise that basic set-up.

“The next thing in line was cylinder heads, because we ran into numerous problems trying to machine the ones available on the market. Our ‘porcupine’ head had some unexpected advantages. Surprisingly cylinder head weight is important. Everyone thinks it’s all about fin area but it’s also about how much energy the cylinder head can absorb. Conduction is a much faster process than cooling through air fins, so by having a large contact area it helps soak the heat into the aluminium casting and then get rid of it through fin surface area.”

Doing business

One unusual part of Gran Turismo’s business model is the difficulty of obtaining items directly from them — they are not easy to find: “I will sell directly… if you can find me then you’re probably the type who doesn’t need too much support with the build, but I get very cautious. Yes, I make a bit more margin if I sell direct, but it’s not in the interests of scooterists who end up with no local dealers as selling the kit is only part of the equation. Dealers can build the engine and service the bike, and that’s better for the customer. Building engines is not my area of business. I’m also not interested in exclusivity deals. If dealers stock my product alongside others then that gives the consumer a choice. A situation where one or two players dominate any market is always bad for the end user. I’m a firm believer in relationships. You don’t need to be in a laboratory with lots of diagnostic equipment. If you can put it together on a driveway and it carries you across Europe, that’s what the average scooterist needs.”

Balancing cranks

With all products in the range a key design parameter is that they must be retrofittable to an original Lambretta. The ultimate vision is to produce an entire engine, the latest instalment of which are the new cranks.

“We started to work our way through the engine as customers were asking for more. I saw an opportunity because at the time there were con rods breaking, cranks twisting and the Indian stuff was… well let’s just say nothing was 100% right unless you were paying big money. I decided we could do something different — look at the crank and do the best we could within normal budgets.

“When looking at suppliers it became clear that lots would promise the earth but then outsource the work. They were also only interested in supplying what already existed. If I asked how we could improve things they said the worst possible thing to me: they told me I wouldn’t understand. That was like a red rag to a bull.

“I wasn’t happy with this so talked to a friend who’s a senior lecturer in noise, vibration and harshness. I explained my problem and all the conversations I’d had with people asking if I wanted it balanced for a horizontal or vertical engine, or one balanced at so many rpm. He said none of that mattered, if it’s out of balance at 1rpm then it’s out of balance. The only question is how far and in which direction.

“In simple terms there are forces across the block or forces along the bore, it’s impossible to get rid of them but the lowest stresses are when they are equal, they don’t cancel each other out but it means that acceleration is the same in both directions. He said none of this was a problem and if I paid into the students’ curry fund he’d teach me at the pub and write a spreadsheet for me. So that was the deal we struck and I bought a lot of curry!

“The objective was to have a quality crank under £200. We could do that but were struggling to allow a dealer margin and we’d realised from the other kits that dealers needed encouragement to take things on. We’ve ended up with two cranks, 60mm and 62mm retailing at £235 and £245.

“The next challenge was to find a crank manufacturer. I scoured the UK but they’re not volume crank producers. One company quoted £15,000 for a con rod forging tool but couldn’t discuss metallurgy or tell you the processes. They could make the shape but nothing else. The long and the short was we had to go overseas but with somebody we trusted and I found that in Taiwan. I met the guys at an exhibition in Germany, we got on okay. I’m sure they probably looked at me and went ‘yeah right’ so I think they were surprised when we turned out to be serious. In the end they did a beautiful job. The cranks are as close to stock dimensions as you’re likely to get.

“No shims on the rod so more metal there, press fit and micro pinned crank pin, then surface ground all over. The correct balance was achieved by using injection moulded, glass-reinforced inserts which are machine screwed in with an adhesive. Ours are the only Lambretta crank on the market using this design, which again comes from go-karts.

The big difference is that karts use solid stuffers, but because we are using much bigger pistons we need to make ours as light as possible. They have to be hollow and strong, so the way we achieve that is with the thin web of steel that’s left.

“That web has a pocket that the plastic nestles into. The machine screws are only holding it in tension, the actual shear load as the crank accelerates is held by this pocket, it can’t come away because of the screws. Karting has operated these for years without difficulty so it’s proven technology.

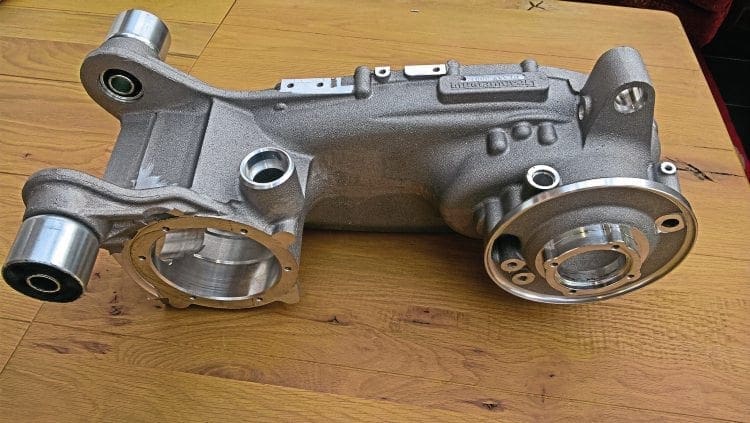

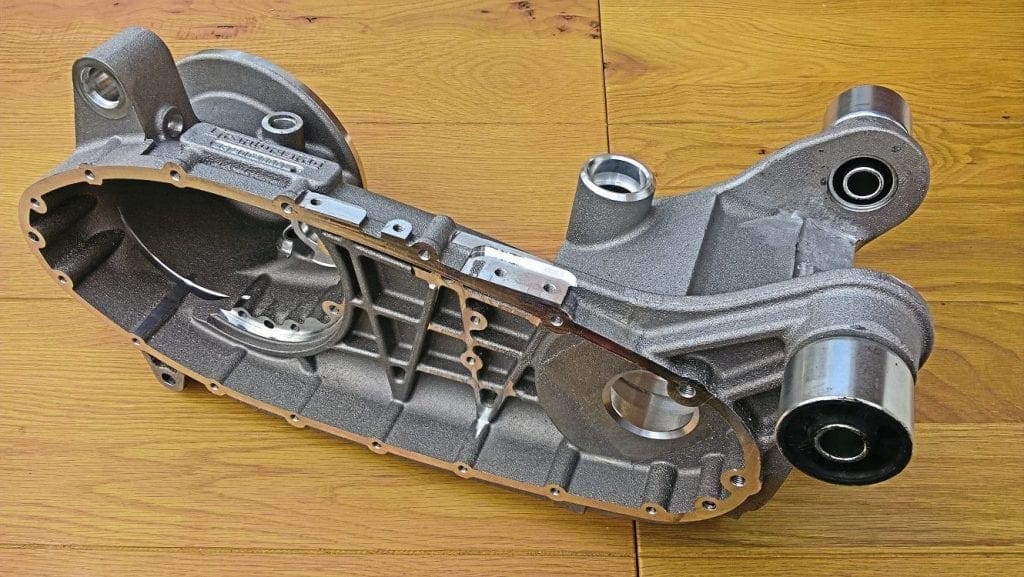

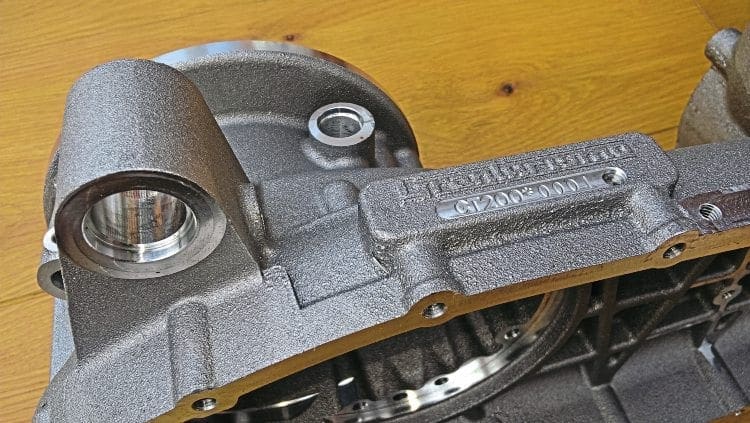

Brand new engine blocks

With each development comes a fresh challenge and Gran Turismo’s plan was interrupted by an increase in the price of engine cases.

“I previously always thought, what’s the point in making a casing? The Indian ones were available and there’s no way I could get close to their price. Then I needed to buy a few 200 SIL casings and the cost was ridiculous, particularly as there’s always remedial work needed on them. I quickly calculated the costs and straight away knew we could do it. The casting was straightforward but the machining wasn’t — I budgeted for three days but it took three weeks. It was an expensive learning experience but now we’ve got a really good quality product.

“The only difference to a factory block is that the transfer ports are larger, in fact they are slightly larger than a TS1 but match exactly the GT200 cylinders. Also if you’ve never built a Lambretta engine this probably isn’t one to start on as there are different techniques involved, primarily heat soak.

“The reason for that is the sections are so thick because we’ve strengthened them with extra metal. It’s simply a question of increasing heating times and using a good quality air heater. Heat it until you’re flinching to touch it and the bearing will just drop in. Every part of it is UK cast and machined, most of it in the Midlands. Soon we’ll have the end-plate sorted, also cast in England.”

What’s next?

“We’ve got some interesting developments this summer. The new casings were designed from the outset to accommodate future projects. I’ve a commercially produced water-cooled barrel that will fit with minimal machining but all everyone seems to want is ‘big’. By the end of this summer I’ll be able to offer a genuine 240cc barrel and a little later in the year an engine with a 330cc air-cooled, iron-lined, barrel.

“The next project after that will be a gearbox, entirely new and capable of handling the massive output of the big engines, in fact existing gearboxes are a big limiting factor in introducing the large capacity motors. They may have to be sold ‘buyer beware’.”

Throughout the visit Richard showed me prototypes, the most impressive of which was a shabby looking SX200. Like everything at Gran Turismo this was no ordinary machine, but one of his slow burn projects: electronic fuel ignition. “It’s entirely possible but requires a steady current — something Lambrettas aren’t famed for. The solution is an Aprilia ignition but that’s far from a straightforward installation.”

I assumed that all of this kept him fully occupied, but I was wrong. “I work for a large company, in research and development. They are fascinated by this and it’s benefited them. One factory had halted production due to seal failure. The shafts had previously turned at 80rpm and used lip seals which was fine, these are what’s used in two-strokes. After recent ‘modernisation’ the shafts then turned at 3000rpm. Everyone got worried and switched over to plain seals, but they failed. I explained two-strokes turn at 12,000rpm so we switched back to tip seals and solved the problem.”

Whether its cylinder kits, fresh cast engine blocks or porting chocolate machines, one thing’s for certain — we haven’t heard the last of Gran Turismo. Further information and prices may be found on the ‘Gran Turismo Performance’ Facebook page.

Words: Stan

Photographs: Stan/Rich Taylor

This article was taken from the August 2016 edition of Scootering, back issues available here: www.classicmagazines.co.uk/issue/SCO/year/2016