The summer of 1979 saw the Mod revival sweeping across the country. What had grown out of a vision from the minds of several purists was now a full blown movement. Mod bands filled the charts and with the release of Quadrophenia imminent, the revival’s popularity appeared limitless.

There came a moment when Mods started to become a familiar sight around London. “There was this sense of excitement that something was happening,” says DJ Gary Crowley. “I started noticing people walking around who were wearing pop-art jumpers and T-shirts and little things like that. You’d also see bands like The Chords and the Purple Hearts cropping up in music press listings. If you loved the energy of punk and 60s Mod, it was an exciting collision.”

With all this activity occurring, it was inevitable that the national press would get wind of the revival. The Sun allotted sizeable column space to new band The Merton Parkas, its headline screaming, “The Mods Are Back! Parkas Lead A Sixties Revival”. While eyebrows were raised at the tabloid’s choice of group, the article succeeded in adding considerable momentum to the resurgence.

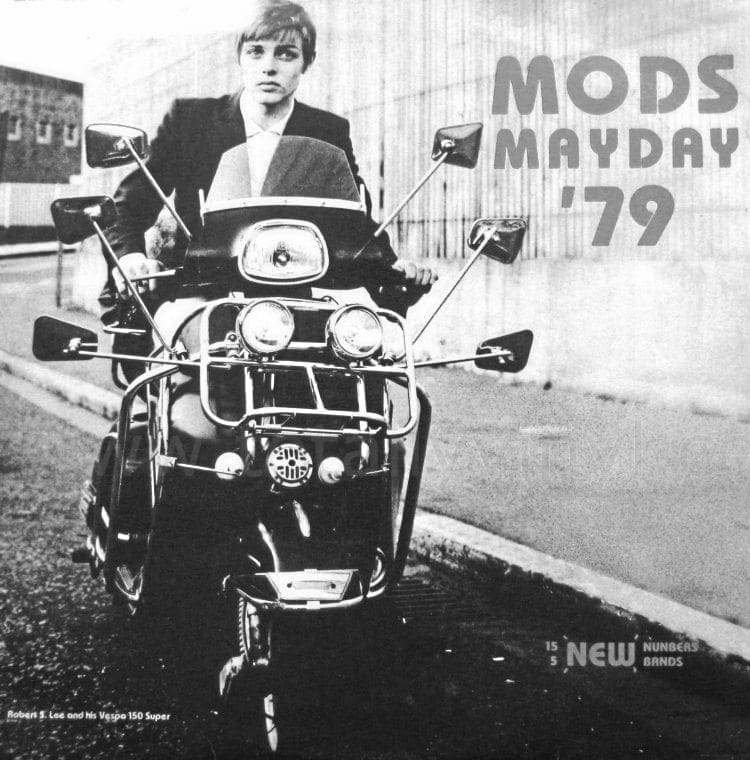

London was still at the core of the movement and themed events were continuing to emerge on a daily basis. In May 1979, Canning Town’s Bridge House hosted Mods Mayday, an historic festival that was later released on disc. Elsewhere, Camden’s Music Machine, the 100 Club, Vespa’s in Charing Cross and other venues were holding regular Mod nights across the capital.

Adding considerable fire to the resurgence, The Who reunited during May 1979. Keith Moon’s death the previous year had all but sounded the death knell for the band, and yet they returned in a defiant mood. With the addition of former Small Face Kenney Jones on drums, Mod’s first wave collided with a new generation.

Such was the interest in The Who’s first show at London’s Rainbow theatre on May 2, 1979, that the group were met by a sea of parkas. Elsewhere, the band would have more personal interactions with their new audience.

“The Mod revival came along and kids were driving around with parkas on scooters,” recalled Who bassist John Entwistle shortly before his death. “I’d gravitated to a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce. I was just about to pull into the driveway to my house and I couldn’t. I’d turned off the road and there was a bunch of Mods sitting on scooters. So my chauffeur beeped his horn a couple of times and they all turned around and went ‘F**k off!’ In the end they moved out of the way as we edged forward. As I was driving past they were screaming abuse at me (saying) ‘Fucking old bastard’.

“A couple of them had Who signs of the back of their jackets. I guess they never found out who I was. All I was doing was trying to get in my bloody driveway.”

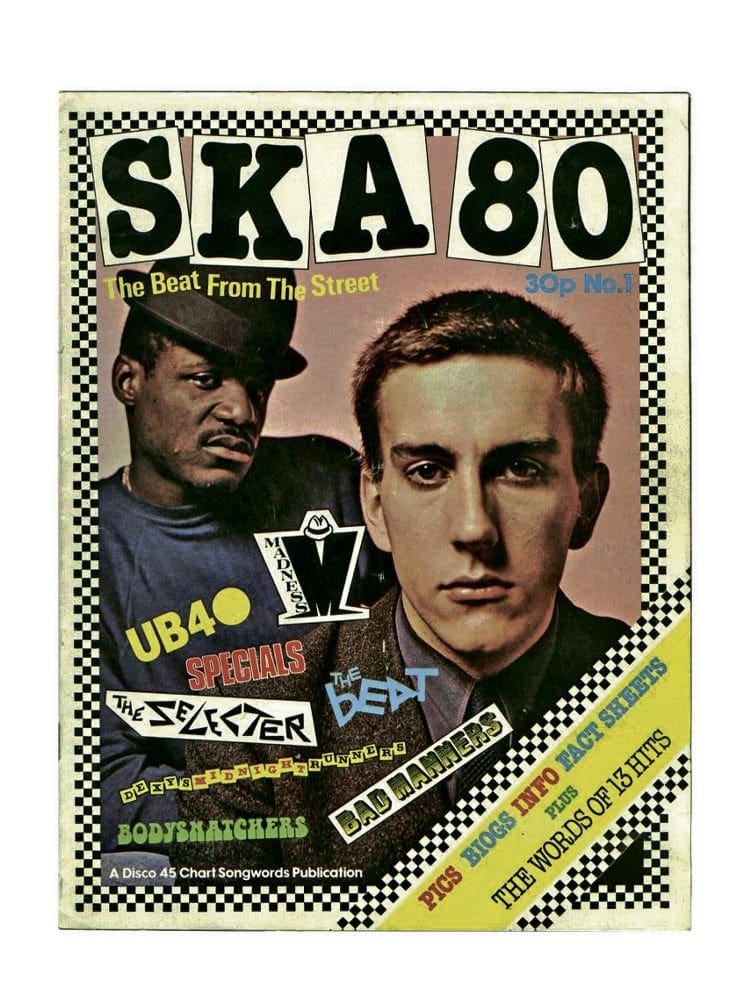

While The Who and other 60s bands were receiving a renewal of interest, soul, Blue Beat and ska — all regulars on the Mod playlist — were given a massive platform courtesy of the revival. With the likes of The Specials, Madness, The Beat, Selector and The Bodysnatchers reinterpreting these classic sounds for the new generation, several sub-genres were being created.

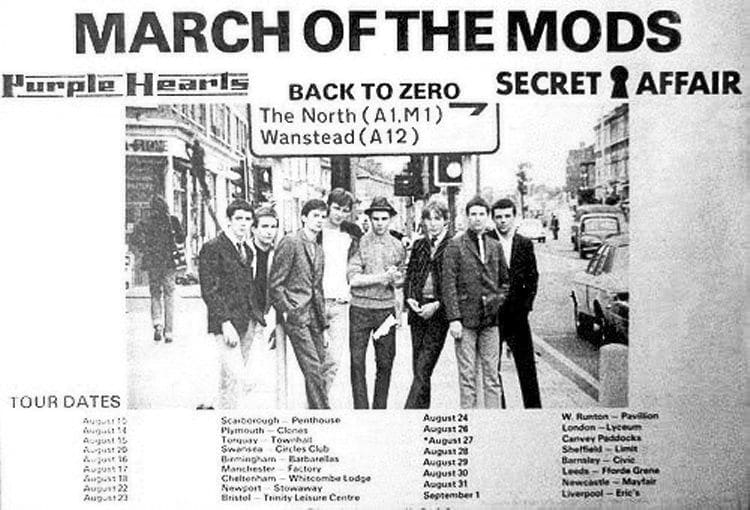

Mod’s new wave reflecting more immediate atmospheres, the demand to see the current crop of bands was enormous. To satisfy the interest, an alliance of Secret Affair, Back to Zero and The Purple Hearts took to the road during the summer of 1979. Under the March of the Mods banner, the 17-date tour criss-crossed the UK, awakening many to the movement.

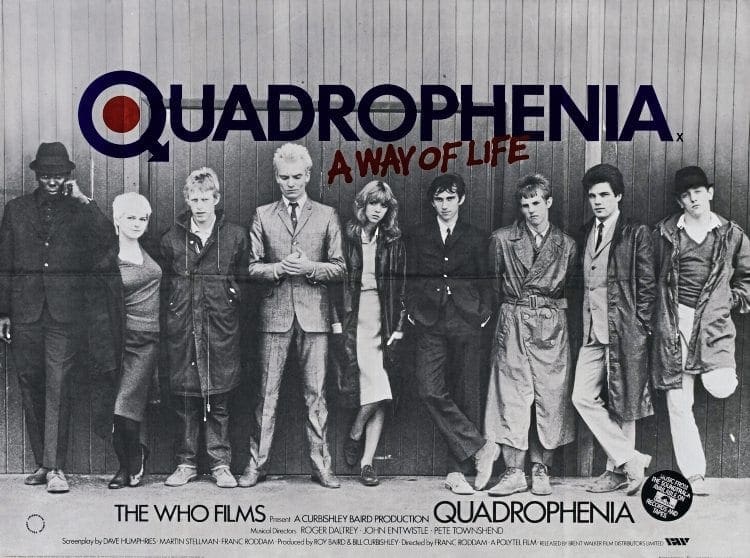

After months of fevered expectation, Quadrophenia was finally premiered on August 16, 1979. Exploding over the nation’s screens in a blizzard of publicity, the adventures of Jimmy and his Mod cohorts sent the revival into overdrive.

“It was a revelation,” says Dave Edwards, one of the Mod scene’s most respected DJs. “After seeing Quadrophenia it all made sense. There was a whole package here; going out, having fun, riding scooters that looked great. It all appealed to me.”

“I’d always had an interest in clothes, so I was ready for something to happen,” reflects Mark Baxter, co-author of the The A-Z of Mod. “Quadrophenia was a very big thing on my estate. It was all word of mouth. The older boys around where I lived were saying, ‘You’ve got to go and see this film!’ It turned into a sort of rite of passage.”

More than any other factor, Quadrophenia served to spread the Mod message across the nation. With the revival at its peak, even the heavyweight Sunday press got involved, The Observer’s magazine of September 2, 1979, devoted its front cover and main feature over to the resurgence.

While punk had been restricted to mainly urban areas, Mod was igniting interest in places not normally receptive to revivalist movements. By the autumn of 1979, it appeared that the whole country had gone Mod crazy.

“It was massive,” reflects Michael W Salter, author of Punks On Scooters: The Bristol Mod Revival, 1979-1985. “In Bristol, you’d walk into the city centre at weekends and there’d be a sea of green parkas everywhere. Even the punks were wearing them over their punk gear.

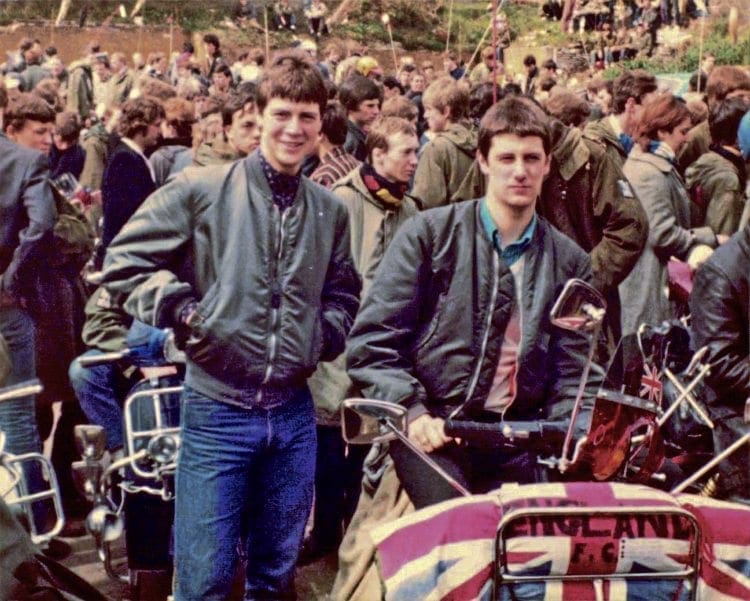

“For us it was the holy trinity; the scooters, the music and the fashion. We were looking for the next thing to come along, and we were happy that what came along had scooters as transport.”

With clothes and music caught up in the revival, interest in scooters was similarly elevated by the Mod resurgence. Following the tempestuous years of the mid-1960s, scooter clubs across the UK were largely the torch carriers for the movement. Dorset’s Modrapheniacs scooter club was one of the few organisations operating in the south of England before the revival took hold. While the club had provided scooters and extras for Quadrophenia’s filming in September 1978, nothing prepared them for the reaction the film generated.

“Prior to Quadrophenia coming out, we were a very isolated group in Dorset,” says Modrapheniacs founder Rob Williams. “We would probably get a maximum of about 20 on a Sunday ride out, and that was from across the county; that was as many as we could muster. Once the film was released, the club swelled to over 100 members. It just went nuts after that. In fact, there were so many people trying to join the club it got out of hand, and quite a few other clubs sprung up as a result.”

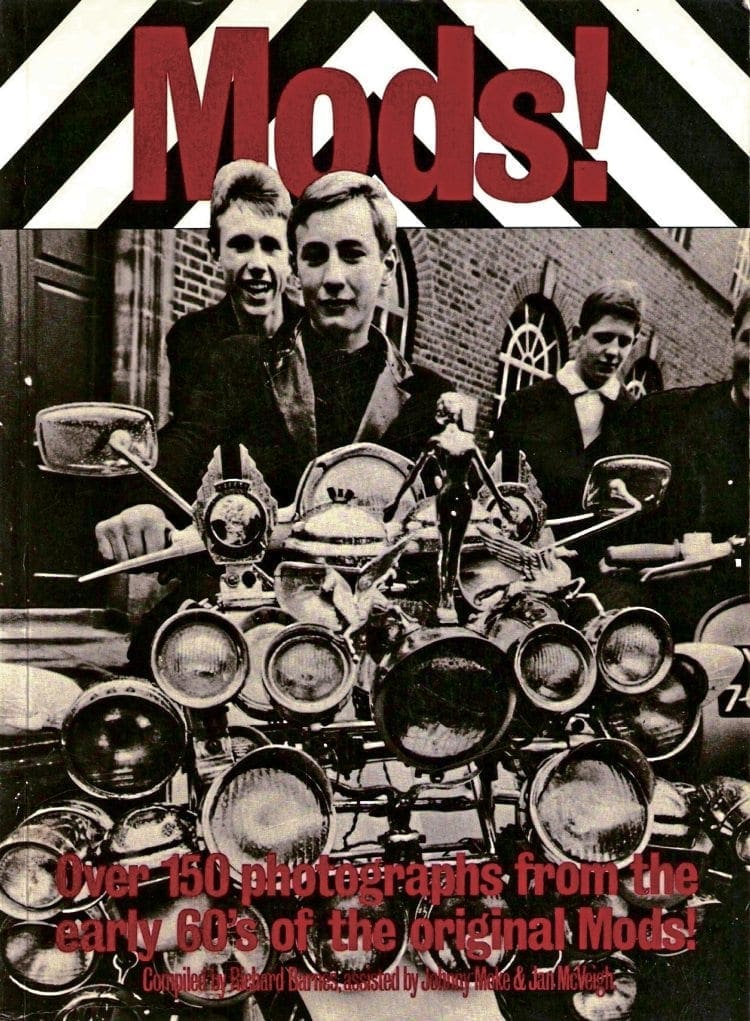

A virtual ‘Haynes manual’ to the style of the movement was the publication of Richard Barnes’ book Mods in November 1979. While the text was anecdotal and entertaining, it was the photos of the original scene that were undoubtedly the main feature of the book. Released through Eel Pie, Pete Townshend’s publishing house, Mods became the absolute bible of the movement and the style guide of the moment.

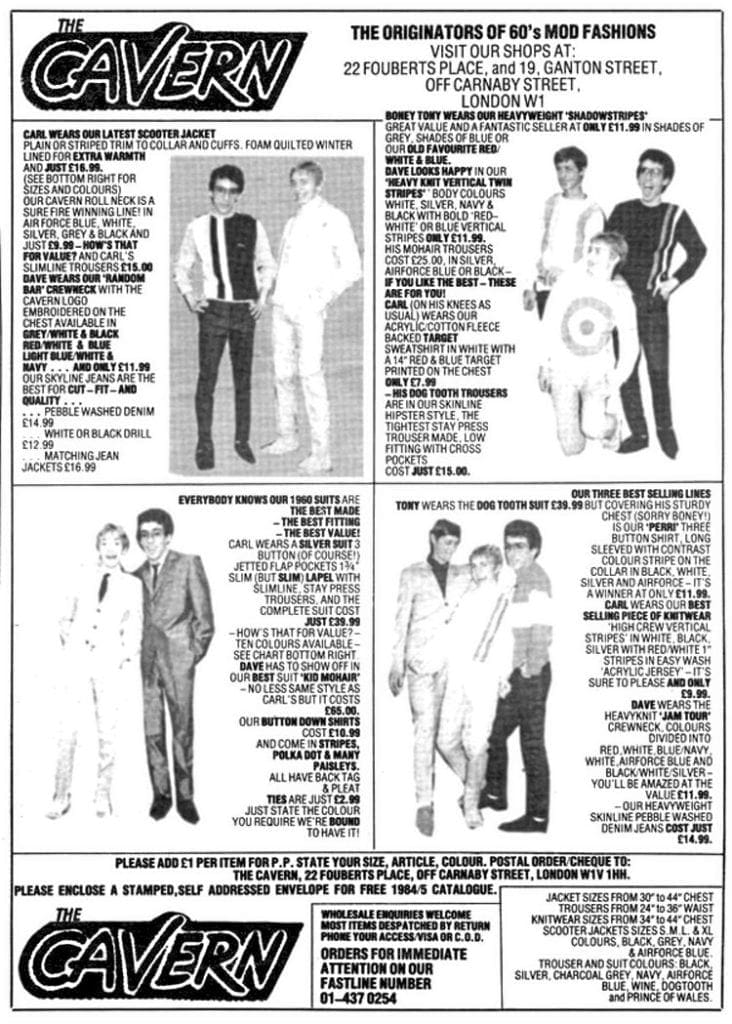

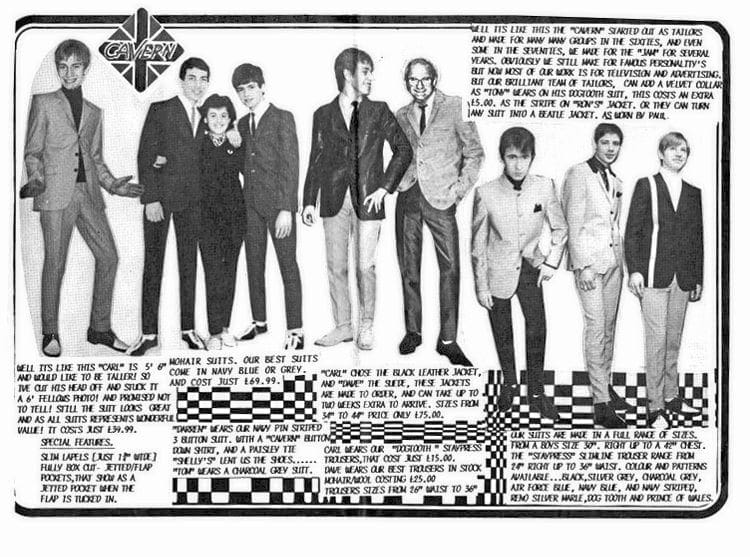

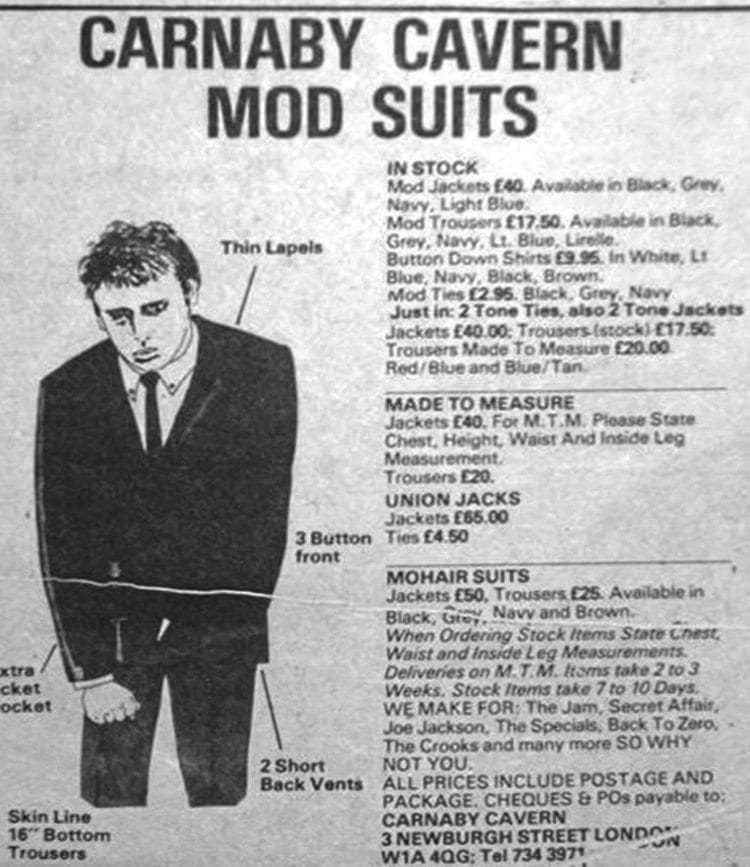

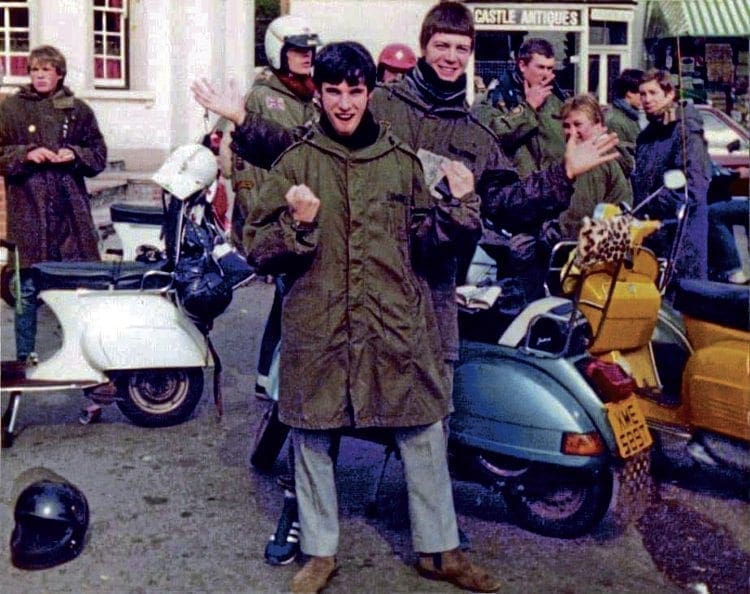

With no single landmark symbolising the revival Carnaby Street, once the epitome of ‘Swinging London’, underwent a massive resurgence of interest. Shops such as Carnaby Cavern, Sherries, Merc and Melandi providing cheap and accessible clothes, weekends would see the narrow west London street congested with the new Mods on the block, either window shopping or generally hanging out. Such was Carnaby Street’s pull, many would travel considerable distances to wallow in this Narnia of Mod.

“There wasn’t much to be had in Bristol,” says Michael W Salter, “but then to suddenly go to Carnaby Street and see all those wonderful clothes — it was amazing. We thought no one down here was interested in selling those sorts of things, and then to go up to Carnaby Street, it sort of confirmed to us it was okay to wear this stuff.”

While the formative stylists placed great store in purchasing unique and rare clothing, many neophyte Mods were less particular. Parkas, initially a necessity to protect delicate clothing, were now a de rigueur component of the revivalist uniform. While the addition of patches, badges, Union Jacks and hand-written motifs may have enraged the purists, these additions were an important part of displaying one’s affiliations during the revival. With army surplus stores churning out parkas by the tonne, the nation’s youth were close to submerging in a sea of green.

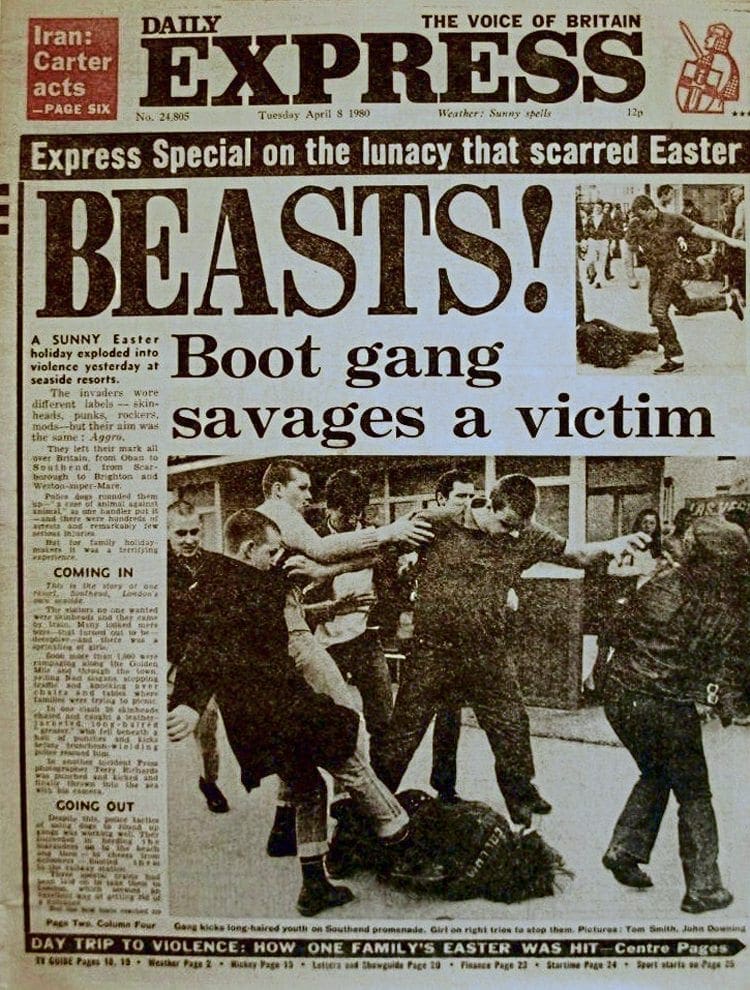

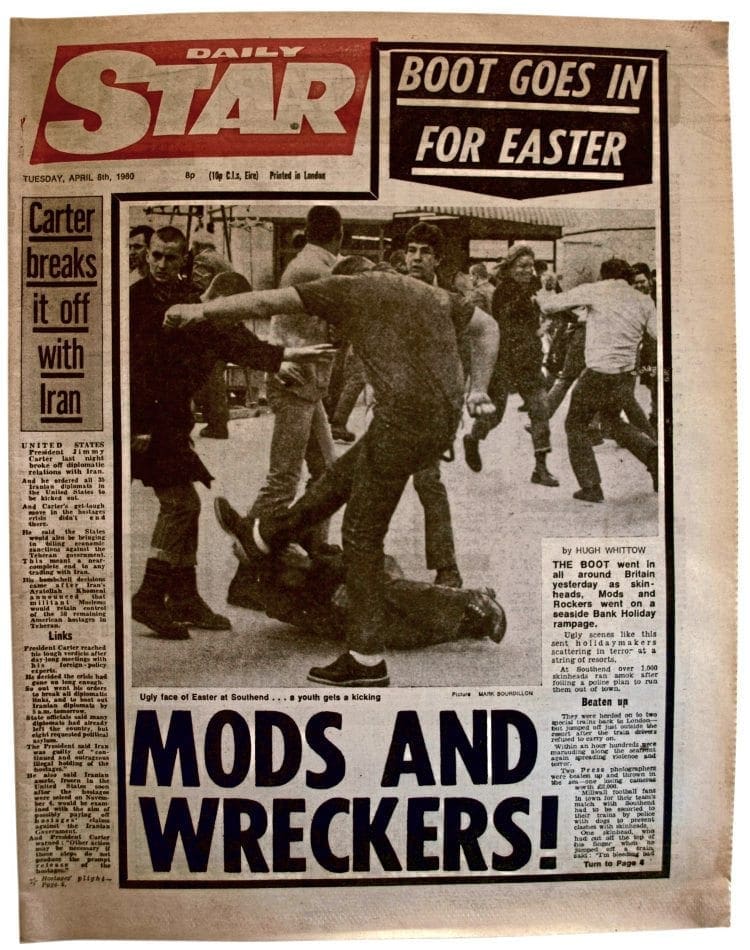

With Quadrophenia driving the Mod bandwagon, some unsavoury elements began to surface. Given that the film had violence at its core, it was predictable that a minority would be inspired to re-enact some of what they’d witnessed on screen. With sections of the rebranded skinhead movement clearly up for a scrap, the stage was set for violent confrontation.

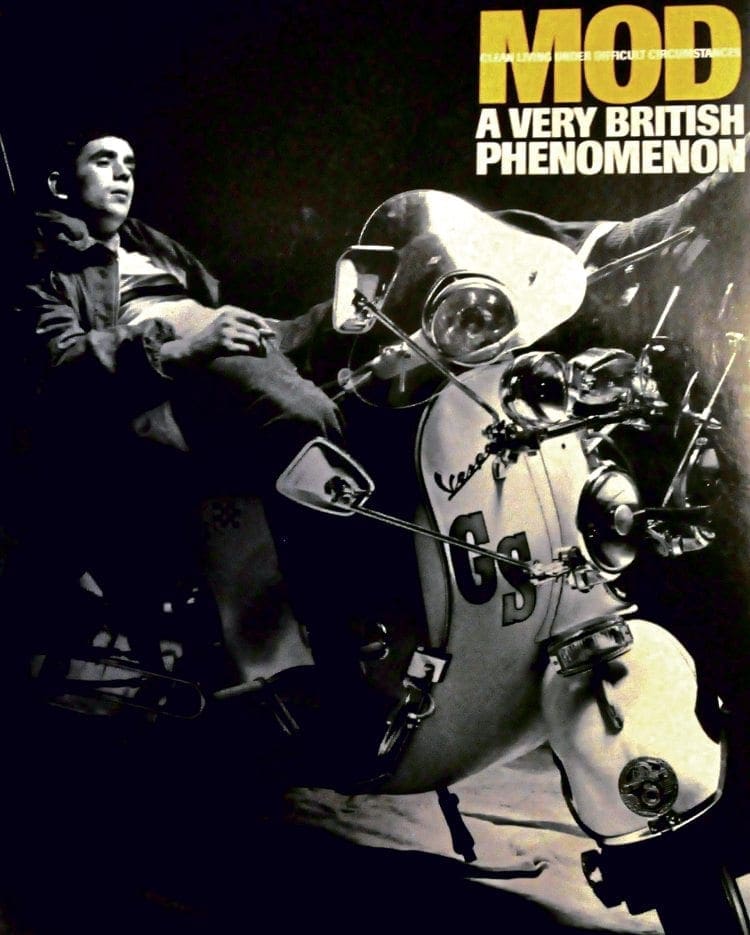

“It was like fighting the wars,” recalls Terry Rawlings, author of Mod: A Very British Phenomenon. “I remember some skinheads bringing in a coffin with a mannequin of a Mod into the Wellington pub in Waterloo. They’d dressed it up and it had a parka on. They walked in with it and put it on the bar.”

Tensions rising, the May bank holiday of 1981 saw the most sustained violence. While the revival had slowly started to lose its craze status, many still dutifully followed the trail to Brighton; clubbing, parading along the prom or riding scooters. However, others were gearing up for chaos.

“Word is out that a load of Mods from Scarborough are coming down here,” reported one skinhead to Brighton’s Evening Argus. “The only reason they come is because of that film Quadrophenia. All these young kids just copied it to follow the trend. They go around with their scooters and tonic trousers like something out of Quadrophenia and they have the nerve to take the rise out of us. We hate everyone of course, but we hate the Mods and soul boys the most, ‘cos they’re flash.”

Ironically, much of the fighting occurred in locations that Quadrophenia had utilised for filming. Predictably, the media lapped up these battles, and with graphic photos garnering front-pages, Mod was in danger of becoming a dirty word. Similarly, the music press (who’d welcomed the revival) was now turning its back on the scene. The Jam explored more exotic avenues of sound, and with many nouveau Mod bands either broken up or relieved of record contracts, the revival began to fragment. Youth culture on fast forward, it would be ska and 2-Tone that would steal the mantle from Mod. In time, other fads would take hold.

“The music press hated Mod,” says Terry Rawlings. “They hated it with a vengeance. This was at a time when you had rockabilly revival, ska, Polecats, Stray Cats etc. There was so much around, and yet they really hated Mod.”

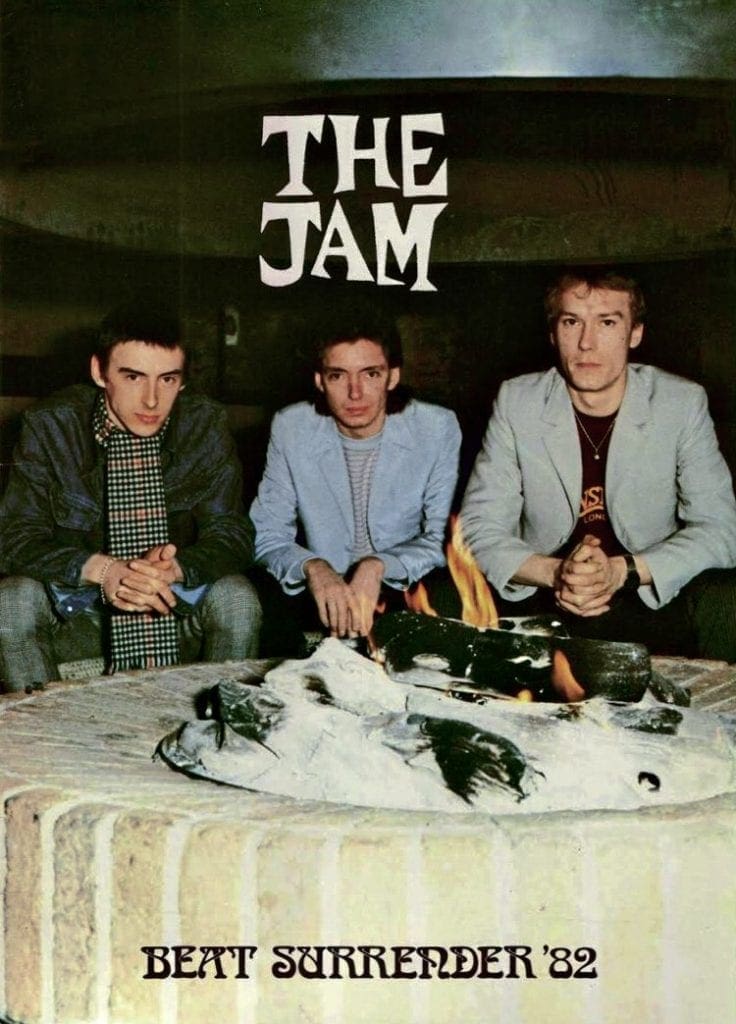

The curtain call to the revival would ultimately come from the band that was primarily responsible for its inception. On December 11, 1982, at Brighton’s Conference Centre, The Jam would play for the last time. With jeering and bottles thrown during the concert, it was a dismal end to Britain’s most exciting band.

With The Jam history, the revival had lost its most articulate ambassadors. Youth culture taking a futuristic turn into New Romanticism, Mod’s monochromatic approach was heavily out of step with the flamboyant new mood. Equally, those who’d initially flirted with the scene were now falling away.

“There was definitely more life before Quadrophenia,” reflects Terry Rawlings. “What came after was awful. It was when Carnaby Street took over and people started getting parkas with patches sewn on the back.”

“After punk there was a huge number of young kids looking for the next big thing,” says Paolo Hewitt, a noted authority on Modernism. “With the success of The Jam, Mod was an obvious target, and it was inevitable that record companies and the media were out to find something new.”

“The revival is mixed up with the popularity of the Jam,” says Mark Baxter, co-author of The A-Z of Mod. “There weren’t enough bands out there making great music to keep it going. In the clubs they weren’t into that sort of music; they were into old 60s stuff, they were looking back. Not enough new music was of interest. It was there for a while and then it was gone… everyone I knew moved on very quickly.”

For some, moving away meant diving into the casual/soul boy movement, a scene closely allied to football culture. For others, the revival would prove to be an entree to a lifestyle they would carry through to this day. Whatever merits the revival had at the time, being in the eye of the hurricane during those years has left an indelible mark on those who experienced it.

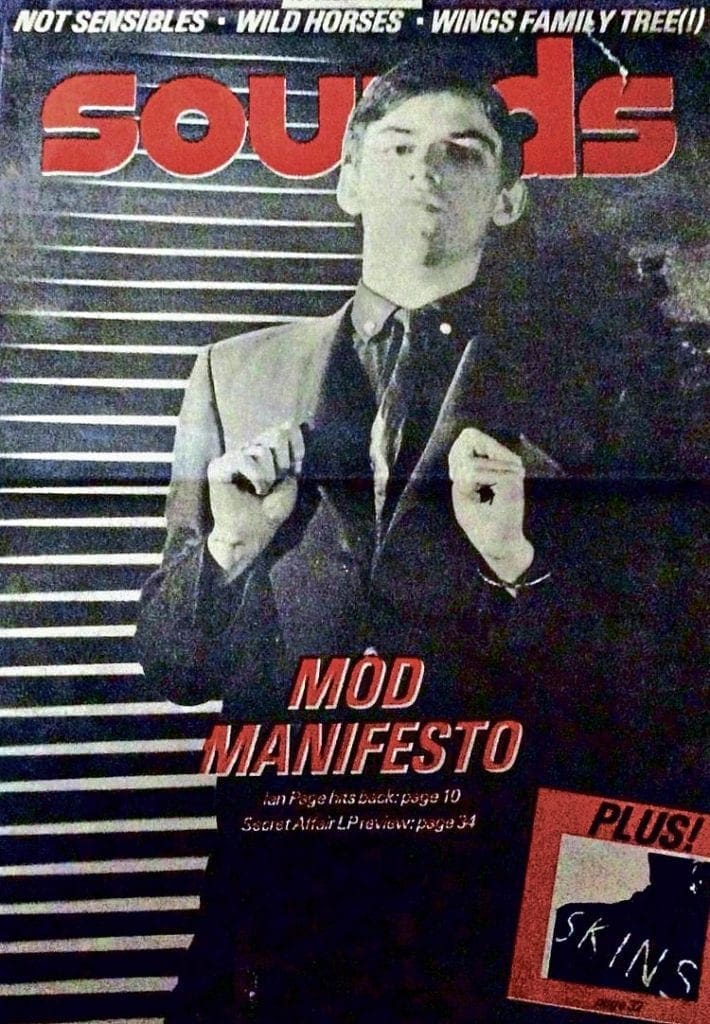

“When people talk about a Mod revival or renewal, that was just a tag,” says Dave Cairns, guitarist with Secret Affair and composer of the Mod anthem of 1979, Time For Action. “What people miss is that Moth never went away. The publicity with the tabloids might have gone, but Mod culture has never gone.”

Simon Wells