Taking inspiration from an idea and putting your own mark on it is one thing; doing it several times to a high standard is another…

When it comes to customising a scooter, whatever make or model it is, we all need ideas to help with inspiration from one source or another. It’s almost impossible these days to create something totally unique but that doesn’t mean to say you can’t perfect an already existing format. Sometimes this allows for a whole host of creative solutions to materialise when the person doing it is a talented engineer.

Front cover

Neil Heppenstall has been involved in the scooter scene for some 25 years or more. His first scooter, an old PX 125, was initially purchased from a newspaper purely as a form of transport to get back and forth to work on. He played in a band at the time and many of those who followed them turned up to watch on scooters. Slowly, Neil’s interest in the Vespa just being a commuter vehicle changed to one more of leisure and the vibrant scene that went with it. His foray into the world of customising was no more than a tin of black Hammerite paint daubed all over the bodywork. Not a show winner by any stretch of the imagination but was it a sign of things to come.

Firmly entrenched in the ways of the traditional scooter style Neil had no thoughts of ever changing his thinking. As the auto era dawned at the turn of 2000 he like many others frowned upon their inclusion into the scooter scene. When Piaggio joined in on the auto revolution it began to change the minds of many traditional scooterists.

This included Neil as he began to look at what he was riding in a different way, certainly in terms of engineering. Seeing an auto hybrid on the front cover of this very magazine in 2010, he had the inspiration he was looking for. His first attempt at an auto conversion was born more out of something to do in the shed at night rather than a full custom scooter. Having acquired a Piaggio Skipper on the cheap from a salvage yard the initial idea was just to get it going. Once worked on, the now running machine took on a new guise when a rather tatty old Vespa VBB frame was grafted onto the Skipper chassis. With the paintwork blasted to bare metal then lacquered over, it had a real ‘don’t care’ attitude look about it. What it did have though were great acceleration, vastly improved braking and better handling. With its odd look and finish, it gained great attention but Neil noticed a lot of it was complimentary, probably because it was something different. It certainly got him thinking about doing another but this time much more refined. The more he thought about it, the more he also noticed how his attitude was changing towards the scooters he had once despised. He summed up what was happening in one quick sentence “the dark side was pulling me in”. It certainly was but not in the way most of us would imagine.

Obscure choices

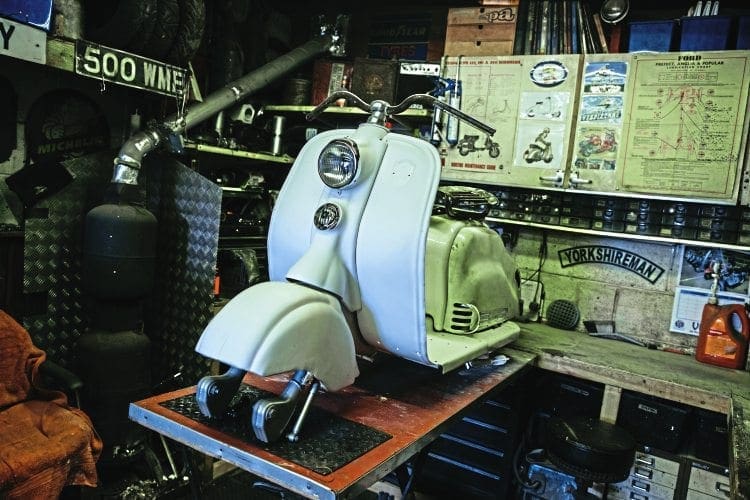

Having got the bug to do an auto conversion the normal way forward would be either a Lambretta or Vespa. Neil wanted to do something different though, and set about doing the conversion on an NSU Prima instead. Neil has always been a fan of the Lambretta LD and its sleek lines of styling, the Prima being virtually a copy of the LD was a perfect choice. At a custom show, he browsed over a Prima on display and was inspired. Having purchased one for £100 or so, minus its engine, it was meant to be a standard restoration originally. Unfortunately, it was a struggle to find a genuine engine so in a moment of madness he decided to use the original Vespa VBB conversion as a donor.

The old Vespa frame was removed and the Prima bodywork altered to fit. What came out of it all was something totally unique. The looks were of a classic 1950s scooter but hidden underneath the performance and handling of a modern day machine.

Until a closer inspection is made, it’s difficult to notice exactly what has been done. The performance though is the real giveaway. Though the Prima had more power than the Lambretta LD, even then it was rather slow both on acceleration and top speed. Now with the modern auto engine fitted it can keep up with the best of them.

This is what started to happen with fellow scooterists keen to see what was under the panels when Neil pulled over. Expecting to see some sort of tuned engine they were more surprised to see an auto one instead. It was a testament to Neil’s engineering skills that he can do such a conversion but until the panels are removed you can’t really tell what has been done.

Perfecting the art

Having successfully done the conversion to the NSU Prima, Neil’s next challenge was to do the same with a Vespa. The older the model the more this type of engineering has an impact compared to if you did it to a P-range Vespa for example. Again, this would be done using an early 1950s model as opposed to something more modern or so it would seem at first glance. Neil had two schools of thought during the planning stages. Firstly it is imperative that the looks and styling remain as retro as possible. This means no subframe visible or awkward mouldings on the panel work to hide the engine for instance.

The idea is simply not to be able to spot what has been done underneath from the outside. Secondly, the geometry of the auto chassis remains exactly the same as it was originally including the wheelbase length and engine position. That way the finished machine will handle perfectly when cornering or braking for instance. Altering these dimensions can seriously compromise everything and if not done right may result in a scooter that is actually unrideable.

While all that sounds easy enough on paper combining the two and getting it right is totally different. This is where Neil’s skills came to the forefront, both in planning and execution. Of course, there is a serious amount of fabrication required but the talent is making that part or alteration so perfect you can’t tell if it was originally like that or not. Neil refers to it as “fag packet engineering” but there aren’t many out there that could attempt this type of work or do it to such a high standard. The chassis and engine this time was from a Piaggio Typhoon and the front end from the Vespa VBB frame that had previously been discarded. The back end of the body is where the real magic is done though. The whole piece is made from a piece of ducting pipe and sheet metal. Taking the shape of an old 1950s Vespa but refining it even further. To the naked eye, it’s impossible to tell and looks almost like some sort of concept that was designed at the Piaggio factory. While it may look like a period Vespa the reality is, it isn’t. The workmanship is so good it deceives you into thinking that it is though.

It seems Neil is a man of many talents and not only is he a good engineer but also a good painter. Having spent 20 or so years prepping and painting his own machines has been a real help. Not only does this keep the costs down but if another part needs fabricating for instance then it’s easy to get it painted quickly. Even so, he reckons the price of doing these conversions is around £3500 each. Remember you have to source the auto engine and chassis as well as the vintage bodywork before you can even start. Add in the paint and all the extras and the price soon builds up. The price tag for what has been produced isn’t that much compared to what it could be because Neil does all the work himself. His only costs, in reality, are his time but his reply to that is: “Long winter nights are made for this sort of stuff.”

Reaction

I’m sure there’ll be divided opinion on whether this type of conversion is accepted or frowned upon. Neil openly admits he does get the odd negative comment but you can’t please everyone in this fickle world of scootering. In the main, most have positive comments about what he’s producing. No one can doubt he has a great creative mind and a talent at what he does. That’s what always wins in this game, certainly when it comes to customising and the level of skill and workmanship to see a project through to perfection.

Neil still has an appetite to produce similar work and at the moment is doing a conversion to a Lambretta LD. He’s always been an admirer of Innocenti scooters and is now finally giving that the auto retro treatment. Having seen a concept of an electric Vespa at the recent Vespa World Days this summer has given him food for thought. In the future, he’s seriously contemplating producing a rat rod electric scooter based on a 1959 Vespa 152L2. Yes, you read that correctly and if his previous work is anything to go by then it’ll be well worth the wait. Neil Heppenstall has taken the humble vintage scooter and turned it on its head but in an individual and clever way. His view is simple: “I’m recycling the past.” Couldn’t have put it better myself.

OWNERS DETAILS

Name: Neil ‘Heppy’ Heppenstall

Job: Extraction engineer.

Scooter club & town: VCB, Dewsbury.

How and when did you first become interested in scooters: My dad used to make go-karts out of them in the 70s. They were always around as I was growing up… but I didn’t get one till I was 24, just to go to work on.

What was your first scooter: PX125E.

What is your favourite scooter model: Early Vespas up to the rally models.

First rally or event: Bridlington.

How did you get there: Vespa PX125E and slowly.

Favourite rally: Always enjoyed the ride more than the do, never been into Whitby, but lovely ride there.

Funniest experience with a scooter: Quite a few… the one I can’t forget is a mate filling his newly acquired Vespa with fuel into the frame breather hole. About £15 until it starts coming out of every hole.

What’s the furthest you’ve ever ridden on a scooter: Anyone who rides with me knows I like to go the long way. I hate boring roads with no scenery.

What do you like about rallies: The scooters and people’s ideas. It’s not just Vespa and Lambretta that float my boat.

What do you dislike about rallies: Snobbery – it’s still out there.

What’s your favourite Scootering magazine features: I like a good barn find story or a rare unearthing of something different.

Your favourite custom scooter of all time: No real favourite but I do like to look at photos, then read about it, then another look at the photos and then it makes sense; people tend to miss things in plain sight.

If you had to recommend one scooter part or item of riding kit, what would it be: Long johns, waterproof trousers helps prevent scrotal shrinkage.

What’s the most useless part you’ve ever bought for one of your scooters: New eBay stuff, particularly cast stuff is nasty. I’ve bought a lot of useless stuff in the past, I bought a pair of levers that must have been polished butter.

SCOOTER DETAILS

Name of scooter & reason: I don’t do names for vehicles, sorry.

Scooter model: Piaggio Skipper with NSU body modified to suit Piaggio Typhoon with broken, recycled, handmade body parts.

Date purchased & cost: NSU – 2015, about £110. Vepsa – 2012, about £150.

Inspiration for project: To improve on my standard auto Vespa VBB Rat.

Any specialised parts or frame mods: Both scooters are based on modified automatic frames cut and modified to suit.

Engine spec: Both engines are the same spec…

Kit: 172 Mallossi. Crank: 54mm Racing. Carb: 25mm Dellorto. Exhaust: Prima – modified sterling, Vespa Lowlight – modified PM 59. Clutch: Mallossi uprated springs. Gearbox: Mallossi uprated. Dyno done by: PSN Tuning, Warren Wilkinson Racing.

Describe engine performance, power delivery and scooter handling: NSU – 18bhp, smooth power delivery, comfortable ride. Vespa Lowlight – 19bhp, angry power delivery, low and handles well. The Capri scooter is a bog standard, unmodified 150 Super Brianza. Lovely looking at the missing link between a Vespa and a slimstyle Lambretta.

Top speed and cruising speed: Vespa Lowlight – 84mph top, 70-75mph cruising. NSU Prima – 78mph top, 70mph cruising.

Paintwork & murals done by: Paint by me, fabrication by me on both autos. Capri – no fab, just straight restoration/paint by me.

Is there any powder coating: Yes – local company JH Powder Coating

Is there any chrome: Yes – local company Yorkshire Chrome.

Overall cost: Around £3500 each.

What was the hardest part of the project: Clearance issues and getting them to sit right and most importantly look right without the auto engine giving it away.

Do you have any advice or tech tips for anyone starting a project: Make a plan, dry build, buy the best parts you can afford and have a go yourself.

Is there anyone you wish to thank: Andy and Mick at PSN Scooters, Warren Wilkinson at Wilkinson Racing.

Words: Stu Owen

Photographs: Gary Chapman