Amazing as it may seem, it’s fast approaching 40 years since the Mod revival first exploded in the UK. With fashion, music and yes scooters, all undergoing an enormous renewal of interest, the revival set off a chain of events that would arm many with a passion that has stayed with them into the 21st century.

This huge resurgence in Mod emerged at a time when the conveyor belt of youth culture had gone into serious overdrive. While skinheads, ska, rude boys, and two-tone would find space in this frenetic period of renewal, it was the rebranded Mod scene that created the greatest impact, remaining a defining moment in many people’s lives ever since.

While many will credit The Who’s film Quadrophenia as the starting point for the revival, the scene had been growing for at least two years before the movie unwittingly nationalised the movement in late 1979.

However, during the early 1970s there was little to engage British teenagers with the lifestyle. While Mod’s first wave basked under a powerful spotlight during the middle 1960s, the furious pace of the decade soon consigned the scene to history.

“By 1966-67 Mod was disappearing,” says Graham Lentz — author of the respected book on Mod, The Influential Factor. “By the end of the Sixties, it had split in two. There were the hard Mods that eventually went into skinhead, while the other, softer Mods, moved into the whole flower power and psychedelic scene. Up north however, the scene never really went away. By the early 1970s, the Mods there were starting to ask for faster soul in the clubs, and out of that came what is known as Northern Soul. That would attract a lot of old Mods who loved the music.”

However, for purists based in the south of England, there were sharp divisions with the activities of their Modernist cousins up north.

“Visually, aspects of Northern Soul with scooters and speed were likened to the original scene,” says Paul ‘Smiler’ Anderson, author of the best-selling book Mods: The New Religion. “But it wasn’t really embracing the mentality of looking forward. Down south, they embraced the Modernist attitude far more. They were listening to the latest soul and funk imports, and they’d dance at clubs like Crackers in Soho.”

Despite these small enclaves of activity, an air of complacency enveloped the UK during the 1970s. With the skinhead and suedehead movements occupied by hooligan elements, no accessible youth culture was on offer. The pop charts were rife with self-indulgent acts spouting ‘prog rock’ and hippie operatics, and few bands held any street-level credibility with their audience. Fashion too had become largely remote and often ridiculous, with flares, denim and permed hair seemingly the norm. Similarly, scooter culture had become a fringe pursuit.

Nonetheless, in the bedrooms of many 70s youngsters the genesis of a revival was starting to stir. With original records from the Mod era handed down from older brothers and sisters to younger siblings, these sounds would start to plant seeds in disillusioned minds. While The Who’s 1973 Quadrophenia LP failed to kick start a Mod revival, the stark imagery embedded in the album’s booklet was far more direct.

Elsewhere, there were scant options for the Mod-leaning youth to engage with. While bands such as Dr Feelgood, Brinsley Swarz and Kilburn and the Highroads had some vague references to Mod, it was clear that a revolt would come from another direction.

Ultimately it would be the punk explosion of 1976 that would overthrow the old guard, yet many felt uncomfortable amid the spit and the bile that the movement provoked. While punk unashamedly torn up all that had gone before, buried within the scene were several echoes with Mod. Clothes, despite their distressed look, were nonetheless efficient and largely monochromatic. Hairstyles were also short and in sharp opposition to the flamboyant styles of the glam era. Narcotics too saw a shift from the decadence of cocaine and marijuana, making amphetamines popular for the first time in a generation. But for all the street cred being pedaled around, an elitism occupied punk.

“A lot of the older people in the Mod movement saw punk as being middle class,” says Paul Anderson. “There were a long of hangers-on and poseurs. And punk claimed to be a street fashion – it wasn’t. It was hijacked by the fashion elite. It wasn’t very working class.”

Ironically, some of the music spewed out by the punk bands had echoes with several original Modernist bands – notably The Small Faces, The Creation, and The Who. Even early Sex Pistols gigs would see the band perform versions of Substitute and Whatcha Going To Do About It. Nonetheless, with punk’s uncompromising elders dismissing every atom of the past, any notion of a Modernist revival growing out of the New Wave scene appeared ridiculous.

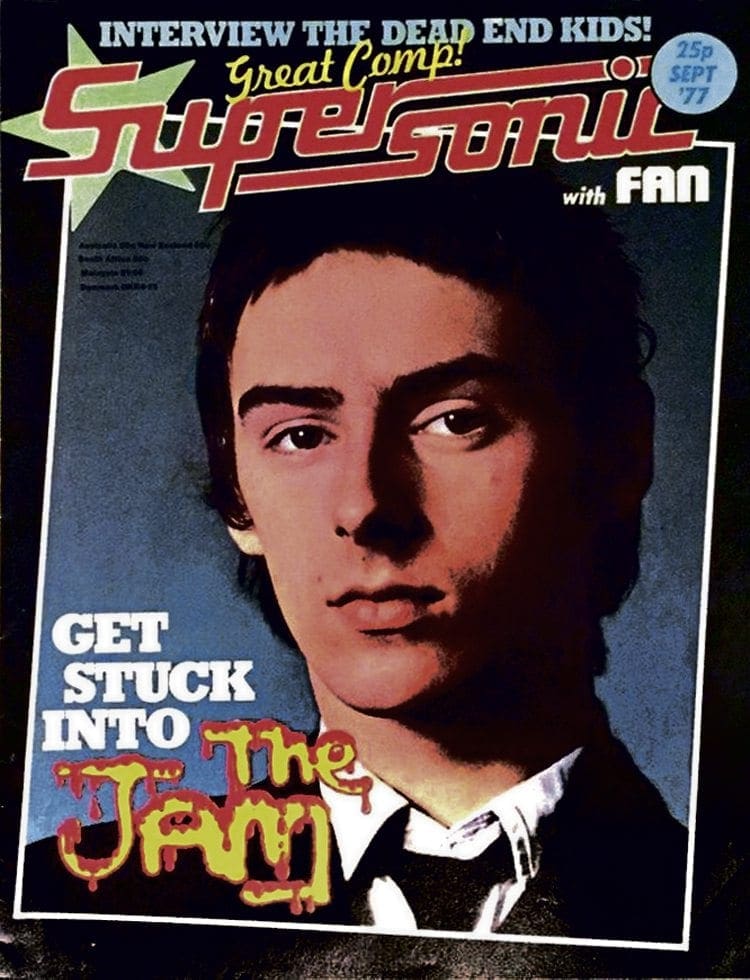

Ultimately it would be The Jam who would successfully infiltrate punk’s A-list, offering the strongest indication that a revival was in waiting. They were led by 18-year-old Paul Weller; the undercover Mod had already drawn out his manifesto for a full-scale Modernist rebirth several years before. His school books displayed an absolute obsession with the Mod ethic and the presence of a parka-clad Weller riding around Surrey on a Lambretta had drawn incredulous glances from his contemporaries.

“I bought a Rickenbacker guitar and a Lambretta GP 150 and tried to style my hair like Steve Marriott’s circa ’66,” recalls Weller. “I felt so individual and arrogant because of it. It was like my own little esoteric world, people stared and thought I looked strange.”

Despite Weller’s Mod obsessions, The Jam collected a broad chapel of admirers during 1977. Nonetheless, bone fide Mods were a rare sight in the punk streets of London.

“I would say there were 20 Mods in the London area,” says Terry Rawlings author of Mod: A Very British Phenomenon. “It was such a small thing. If you saw a Mod on the street you would instantly cross the road to talk to them because you felt you had to befriend them.”

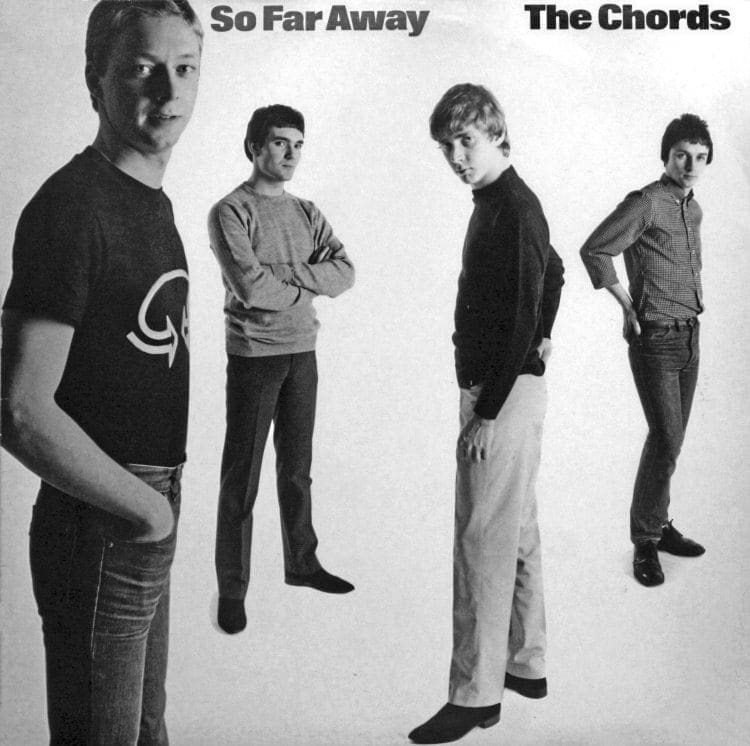

“I thought I was completely alone,” says Brett ‘Buddy’ Ascott, drummer with The Chords. “I didn’t know any Mods. I didn’t know anyone who had a scooter. I saw the advert for The Chords audition and I turned up wearing a target T-shirt and a parka. It was from that moment I realised that there were other Mods around.”

By 1978 many were searching for something fresh. The success of The Jam’s All Mod Cons album left no one under any illusions where their influences lay. With punk considered passé, Mod’s bright colours and all-encompassing lifestyle were proving far more attractive. With The Jam as powerful ambassadors, any notion that it was a backdated movement proved no stumbling block to its ascendancy.

“The Jam was more important in getting the Mod revival under way in the first place,” says Graham Lentz. “It was Jam fans who got to know about them when they first starting venturing into London. People picked up on the style of the band. Through the odd interview the band was doing, it became apparent where their influences were really coming from. They ended up with a devoted, but relatively small army of fans who started to adopt their style.”

Features in Record Mirror and Sounds during the spring of 1978 would serve to explore the new movement that had collected around The Jam’s success. “It’s new for us, we weren’t able to do it first time around,” reported influential London Mod, Grant Fleming. “Mod is a way of thinking. It’s fun loving and smart. It was kids who wanted a laugh, drinking, dancing, girls. Going to gigs and taking pride in yourself.”

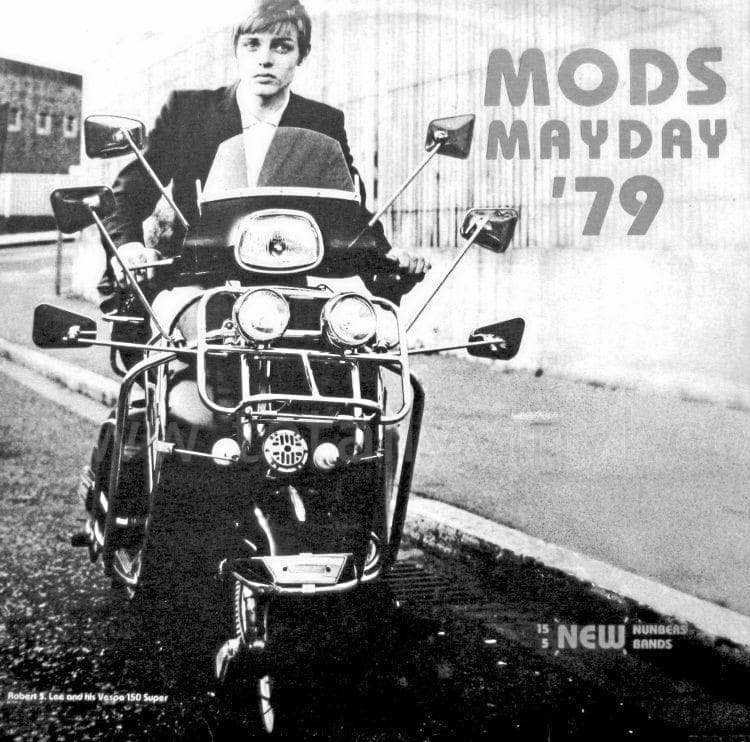

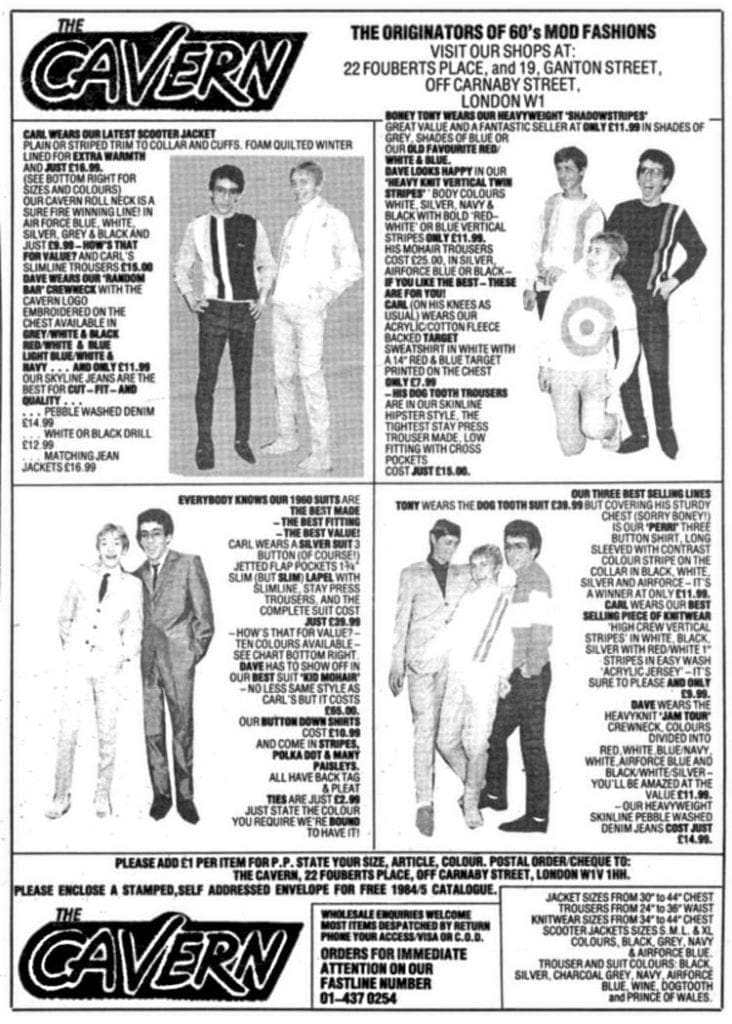

While many were watching The Jam, others were picking up guitars and writing songs. Much like Paul Weller, they fused the energy of punk with everyday tales of teenage frustration and angst — backed with a strong 60s sensibility. Those not disposed to playing music were nonetheless energised by Mod’s fashion sense, and were adopting many of the styles of the movement. Others wanting to fully immerse themselves in the culture were exploring the scooter scene. By the turn into 1979, a sizeable community was starting to appear.

“It’s incredible that word of mouth can be that efficient,” says Chords drummer Brett Ascott. “It was generally underground. I remember very well our first gig at the King’s Head in Deptford, and suddenly 80 Mods turned up. I’d only remembered seeing one or two before. In south and east London especially, there were burgeoning pockets of Mod growth, but I think they were pretty much unaware of each other.”

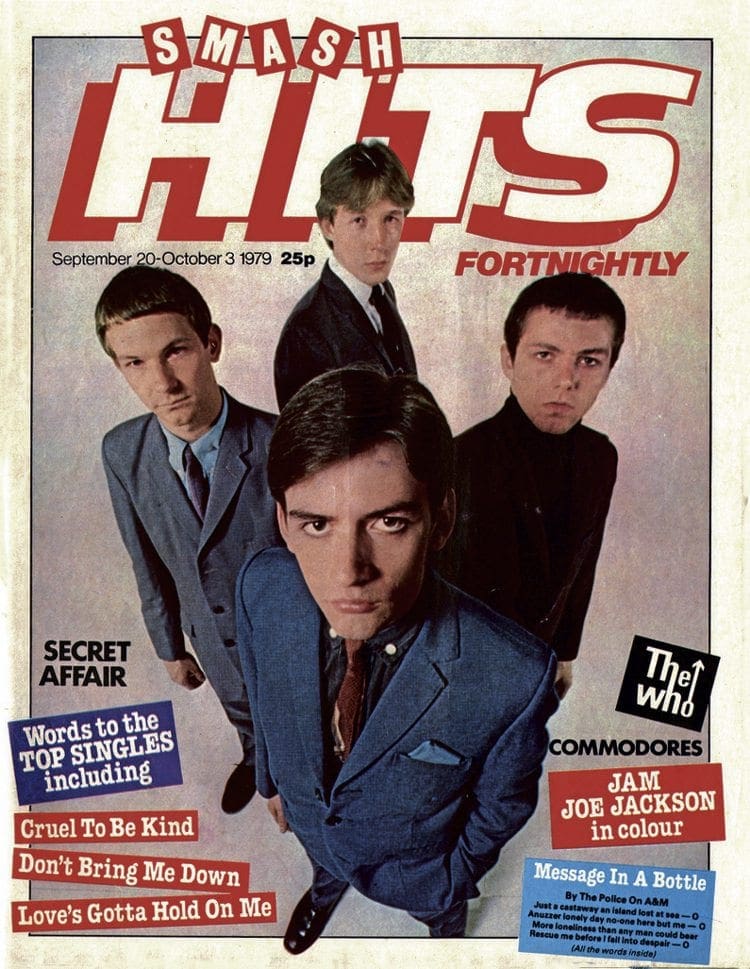

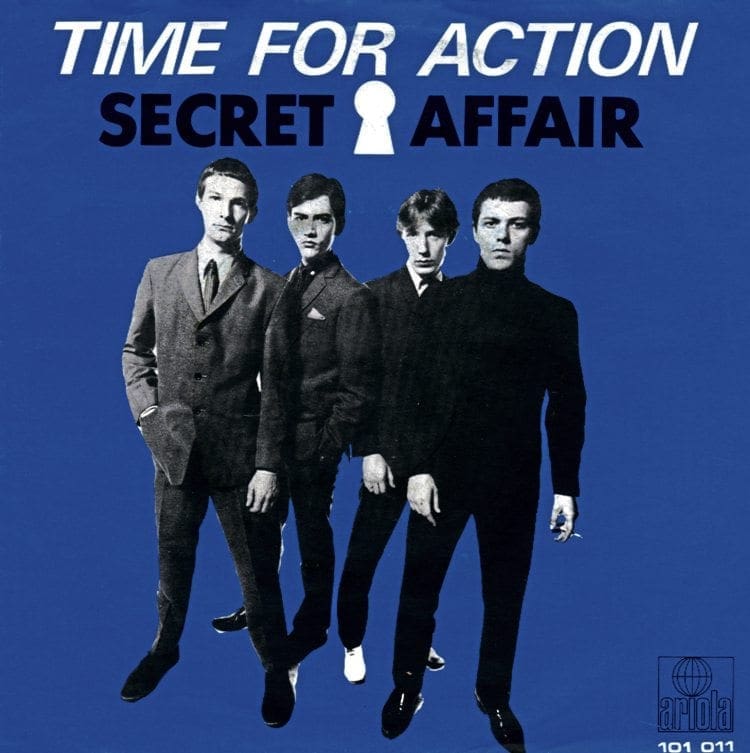

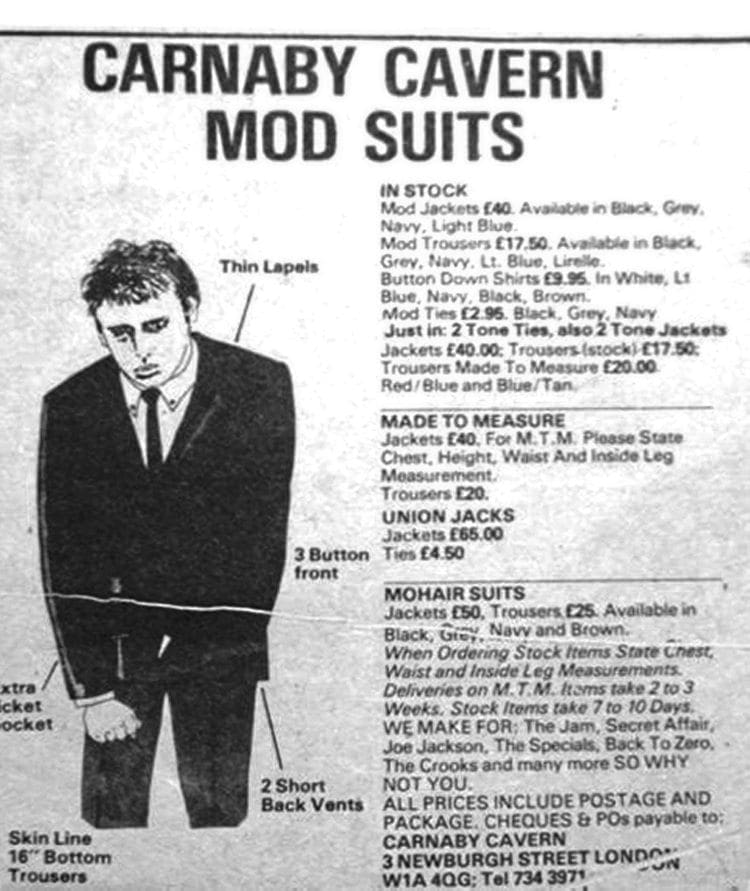

By early 1979, a large army of bands began to break through. Along with The Chords, bands such as Romford’s Purple Hearts, North London’s Back To Zero and the newly branded Secret Affair were courting serious interest around record labels. In their slipstream was a legion of other groups who were picking up on the buzz; The Lambrettas, Small World, The Merton Parkas, Long Tall Shorty and Squire just some of many who formed part of the Mod music scene.

The Jam still dominating attention, a ‘Mod pilgrimage’ to see the band play in Paris during February 1979 drew scores of acolytes; all collected via hastily printed photocopies and word of mouth. This trip served as a gathering point for many who’d previously been faces in a crowd. With energies concentrated in Paris, the scene had very powerful emissaries ready to steer the new movement.

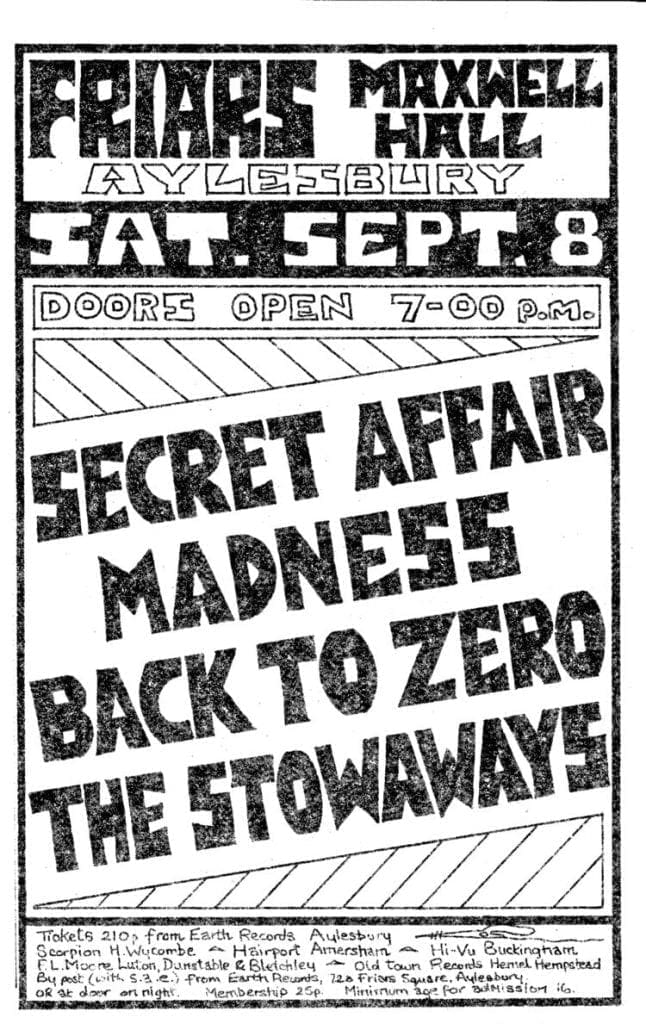

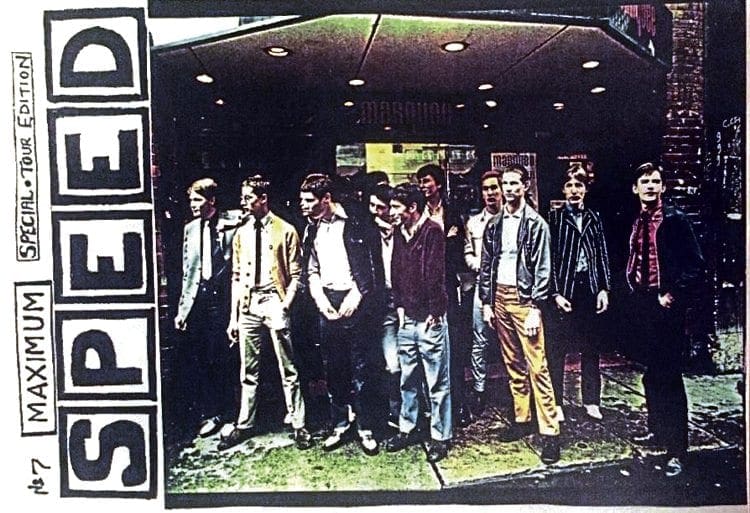

By the spring of 1979, regular Mod nights were being convened across the breadth of the UK. Predictably, London saw the bulk of this activity, with venues such as Waterloo’s Wellington pub, Canning Town’s Bridge House and frequent nights at The Marquee in London’s Soho becoming Mecca’s for the new Mod community.

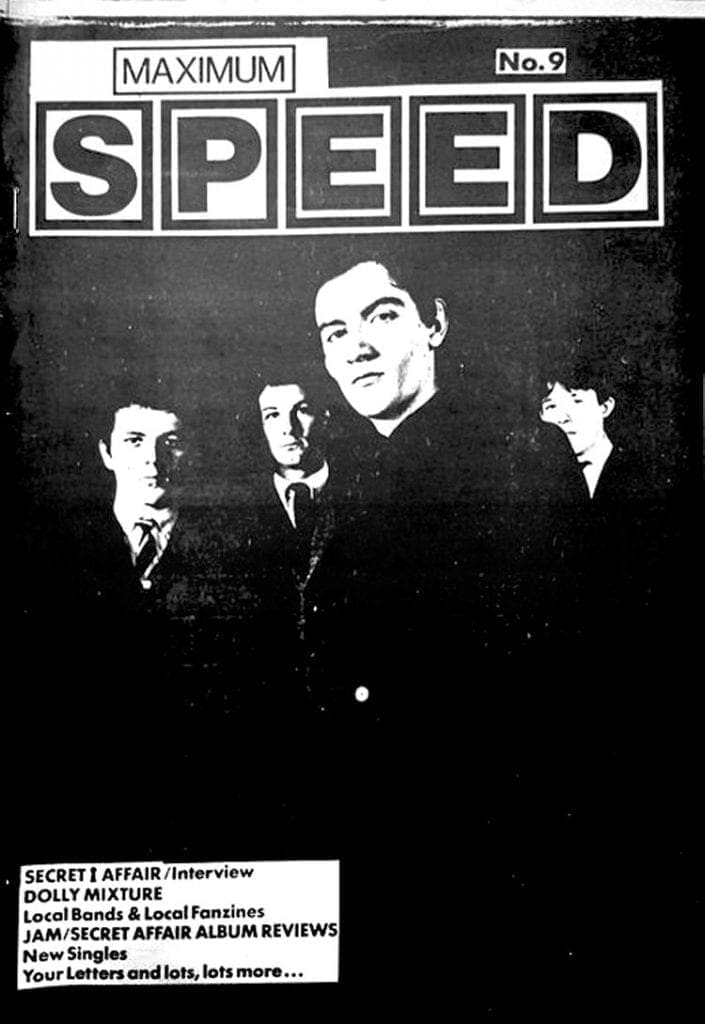

Meeting the demand of the new movement were several fanzines. Much in the spirit of the DIY punk ethic, Maximum Speed was the first Mod fanzine to appear, providing news, gossip and despatches from the front-line of the revival. Soon after the likes of Jamming, Extraordinary Sensations and Patriotic would be reflecting the scene through their pages.

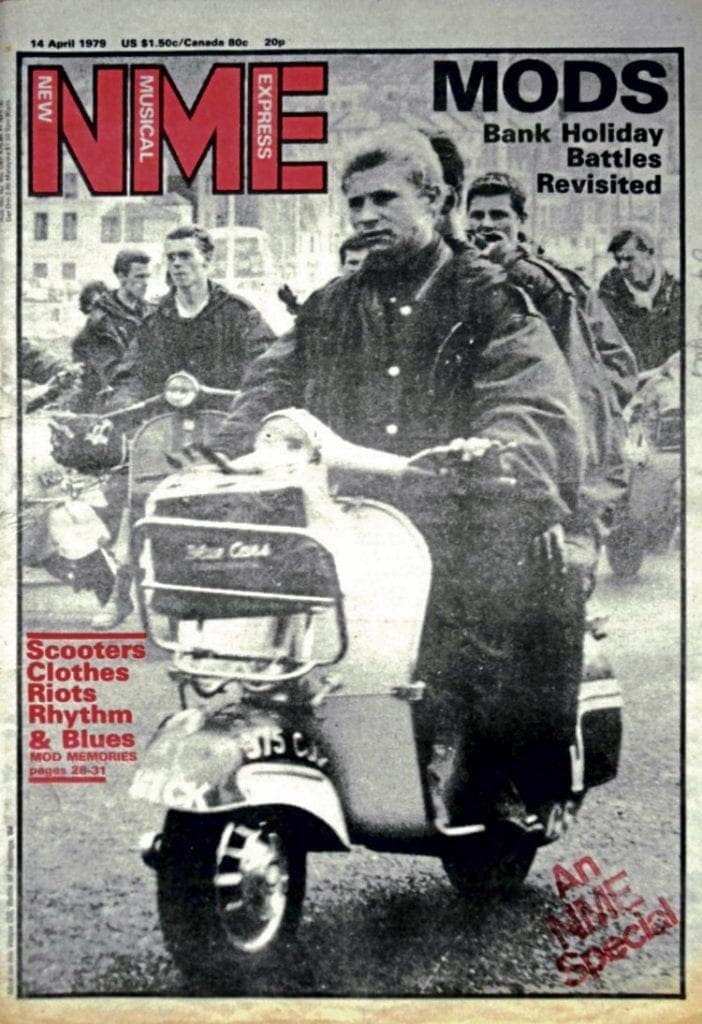

While the music press had been consistent with its coverage of The Jam, the first national feature to seriously assess the Mod revival came in the April 14, 1979 edition of the New Musical Express. Sporting a cover displaying Mods aboard scooters, a four-page article dominated the issue.

While two pages focused on the original Mod scene, the rest of the feature was handed over to the burgeoning revival. Containing interviews with the new crop of bands including The Chords and Purple Hearts, the article was the most sustained resume of the scene to date. With the NME (then) shifting upwards of 250,000 copies a week, word of the revival would be transmitted to all corners of the UK very rapidly.

Shadowing the movement’s growth was the film version of Quadrophenia. Incredibly, the movie had been in active pre-production well before the revival took hold. The film’s producers contacting scooter clubs and associations for vehicles and riders, the buzz on the scene was palpable. Clearly, the new interest in Mod was a major coup for the production, but not something they’d ever predicted.

“When we first started the film we had no idea that there might be a Mod revival,” recalls Quadrophenia director Franc Roddam. “We hoped that we would create one, stylistically, and we hoped that there might be lots of little Mods wandering around the streets, and that would obviously increase the interest of the film.”

Roddam’s optimistic viewpoint wasn’t shared by many. Preserving the disquiet that was being freely verbalised was the 20th May 1979 edition of The London Weekend Television Show, a regional magazine show fronted by Janet Street-Porter.

Canvassing opinion from Mods gathered in Carnaby Street, thoughts weren’t entirely positive on Quadrophenia’s emergence, although it was generally agreed that the synchronicity of the film’s arrival was startling. For those dependent on the movement’s exclusivity, the worry was that the revival could swiftly descend into craze status courtesy of the film’s emergence.

“Quadrophenia’s going to end all that,” reflected one young Mod on the negative effect the film would have on the burgeoning scene. “I’m dying to go and see it but it’s going to end it all, and we all know it. They’re gonna go and see it, come out, buy new parkas, try and get a scooter if they can and end up on pushbikes and end it all.”

Nonetheless, before the film’s release, a summer of Mod was being enjoyed by thousands right across the country. With new bands appearing seemingly every week, and with The Jam on the cusp of even greater successes, there was never a better time to be a Mod.

Simon Wells