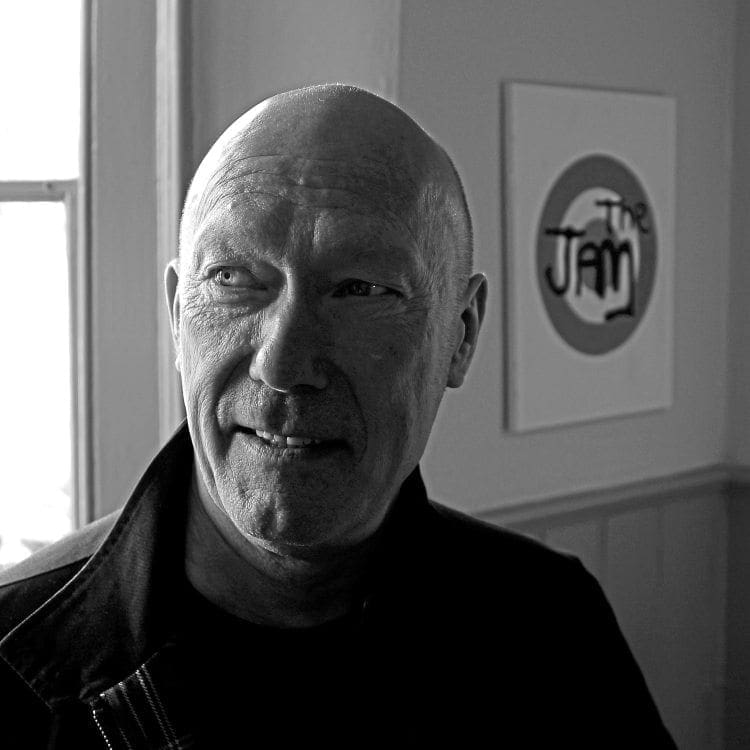

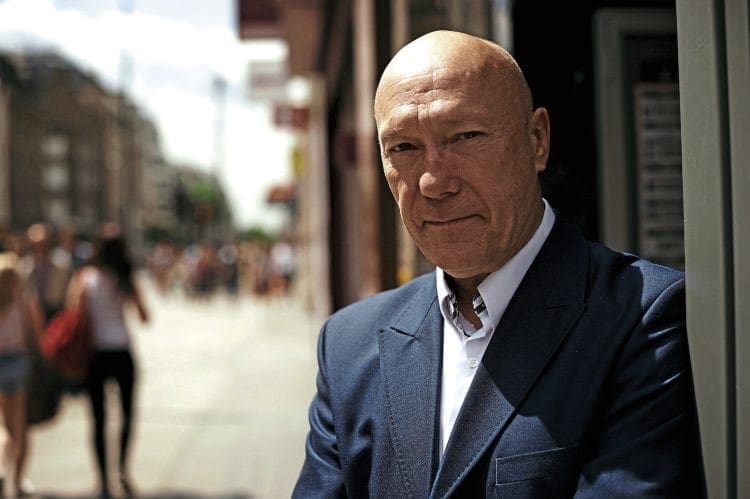

The Start to ’77 is an illustrated novel, co-written by drummer Rick Buckler, based on the Jam’s early years during which they graduated from the Woking working men’s club circuit to London’s exploding punk scene, before ending the Queen’s Silver Jubilee year with a clutch of successful singles and two Top 30 albums. But as Rick tells our man Andy Gray, the band’s big hit before they were famous could’ve ended in tragedy. This is the story in Rick’s own words…

Start

As kids, we weren’t interested in football or shopping, so the music room at Shearwater Secondary Modern in Woking which myself, Bruce and Paul attended, became a meeting place for like-minded souls during dinner and break times. We’d borrow and swap albums among our little crowd which included guitarists, drummers and anybody who was generally interested in music and wanted to play.

I’d formed my own little band with my twin brother Pete and my mate Howard – for some reason I’ve always ended-up as part of a three-piece — but we never did any shows. We were called Impulse, for what it’s worth, and the drums I played I built myself. I made the shells at school and bought all the metalwork and other accessories from Maxwell’s music shop in Woking. The only thing I didn’t make was the bass drum — it was too big, so I borrowed one from Guildford YMCA and took it home on the bus. Paul, who was in a band with his mate Steve Brookes, knew I could play so when his usual drummer, Neil ‘Bomber’ Harris, pulled-out of a show at Woking Youth Club due to holiday commitments, they asked me to step in. I was on board from that moment onwards.

Thick as thieves

I know some people might find it hard to believe, but being in a band with Paul during those early days was good fun. Success not only changed him, though, it changed all of us. When you get signed by a record company, things all of sudden become serious — it becomes your job. But when you’re at school and only playing shows at weekend as we were, there’s no pressure and it’s all brilliant. We were a covers band, doing the working men’s club circuit around Woking and playing Chuck Berry numbers as well as other, simple 12-bar stuff. We’d hang around together, too, At youth club meetings, while others would get chucked out for trying to smuggle in silly little tins of Carlsberg, we were smart enough to get sloshed outside before going in; on Whisky Mac, mostly. We always wanted to be a four-piece, like the Beatles. So we drafted in Dave Waller, a local people’s poet, on guitar.

He was part of our gang and a bit of a socialist. A lovely guy, he was maybe too much of an idealist, which led to him becoming the butt of people’s jokes. I remember Paul removing all the varnish off the neck of his guitar, once. Ever tried playing a guitar with a non-varnished neck? Your hands just stick, Dave wasn’t a great player and ended-up leaving. Tragically, he got heavily into drugs and died as a heroin addict in Woking some years later.

The power of three

Bruce Foxton arrived when Dave Waller left. We only became a three-piece when Steve decided to quit. Him and Paul were really good mates — Steve lived with the Wellers for a time when he had problems at home. The band had been around for two or three years doing the same-old local clubs every weekend and I think Steve felt like the band wasn’t going anywhere. We’d tried to get things moving by sending tapes to record companies, resulting in the usual rejections. We’d also done some recording, so it felt we were moving on; getting somewhere. About that time, 1975, we even supported Thin Lizzy, our biggest-ever gig at that point, at the Greyhound venue in Croydon. They were promoting the Jailbreak album that featured The Boys Are Back In Town and went on to become a huge hit. We went on stage in our embarrassing sartorial ensemble: white kipper ties, white silk bomber jackets and horrible crepe shoes, in front of a hair and teeth audience of about 2000 rockers. We didn’t care, we just loved the experience.

Gigs like that, though, made us realise we couldn’t rely on doing covers — we’d have to start writing our own material. The early songs Paul and Steve wrote were love songs: Lovin’ by Letters, Some Kinda Loving, that sort of thing. There was a transition of sorts with a tune called Blueberry Rock which felt as if it had a bit more substance. Then Paul saw the Sex Pistols…

This instigated a huge change of song writing direction; lyrics, rather than melody started to take centre stage. By then we’d manage to persuade John (John Weller, Paul’s dad and the band’s manager) to let us loose on the London scene. John was happy putting us on the Woking pub/club circuit ’cause we were getting £15 to £25 a night — a lot of money back then. Travelling to play London at weekends didn’t prove conducive to me holding down a steady job. It invariably meant knocking-off early on Friday and starting late on Monday. I was always leaving jobs before I got sacked, which didn’t matter as there was plenty of work around in those days. You walked out of one job, straight into another. On one occasion, I was working at a drawing office when John told us we’d been offered some shows in Germany playing at American air force bases. I was literally going blind at the drawing office. The work was so intense I’d walk home and hardly be able to see 10ft in front of me, so when the Germany offer came through I immediately told my boss I was handing my notice in, and promptly left. Of course, the gigs fell through and Germany didn’t happen, but such was the bountiful employment situation in the mid-70s, no real harm was done.

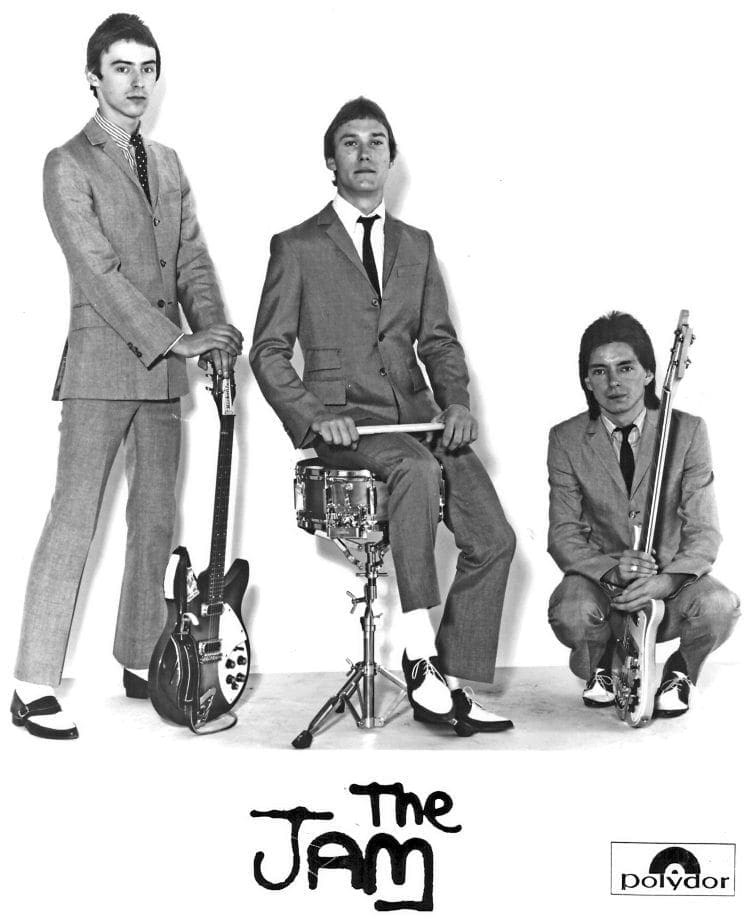

The band had been christened by this time — out of necessity rather than inspiration. Struggling to think of a name to put on the posters, we came up with The Jam on account of the jamming sessions we held at school. Its origins had nothing to do with a breakfast table, ‘pass me the Jam’ conversation between the Wellers, which has been reported elsewhere. I don’t think it’s a particularly good name.

Paul always admired The Clash as a name because it said everything about the music. But as Dennis Munday, our A&R guy at Polydor, said a few years later: “The name is irrelevant — if you’re crap, people will think it’s a crap name, likewise if you’re great, it’ll sound great.” He was right.

‘The screech of brakes and lamplights blinking

Pub-rock, a precursor to punk played by the likes of Dr Feelgood, and the Kursaal Flyers, dominated the capital’s pub and club scene when we started gigging around London. The audience was very mixed and by no means a punk-only crowd. You’d get anyone from old hippies to young kids turning-up. It was only when people saw the Sex Pistols and The Damned that audiences starting separating into tribes. We’d swapped the silk bomber jacket/ kipper tie combination for the black suit/ white shirt look by the time we got to London. I can’t remember who suggested it — it might’ve been Paul — but there was a certain wariness to change, bearing in mind the first image we ran with.

It wasn’t that we were trying to buck the punk trend for dressing down; we thought the black-on-white look of the suits was bold and made us stand out. We didn’t want to look as if we’d rolled on stage off the streets. For us, London was far more exciting than playing to the usual pissed-up Woking working men’s crowd. Travelling to and from the city wasn’t always a pleasure, though. One night, before we were signed, we were driving home having paid a fly-posting visit to London. I was behind the wheel of my customised £25 Mini with John and a bucket of poster paste beside me, while Bruce and Paul followed behind in Bruce’s Ford Cortina. In those days, roadworks consisted of a railway sleeper laid across the road with a little candlelight holder on top — there were no cones then — and unbeknown to me, one of these heavy, metal track parts was laying across our lane as we headed into an underpass on the A3. John, who saw it first, grabbed the wheel, which meant we missed the first one, but about 30ft further up the road lay another one blocking-off the middle lane — that one we didn’t miss. We hit it smack-on, sending the car right over; back-end-over-front. When we emerged from the other side of the underpass we’d landed back on our wheels. John got out the car; his head covered in all this crap, and started screaming: “Aargh, my brains! My brains!” I quickly realised what he thought was blood and brains pouring out of his head was actually the wallpaper paste he’d been sat in the car with. John escaped with a crack in his head and I had a broken right ankle, which I only discovered when I got out the car and gave it a kick. The police accident report, which I still have, basically said the lighting in the underpass was crap, but it was legal.

In the city

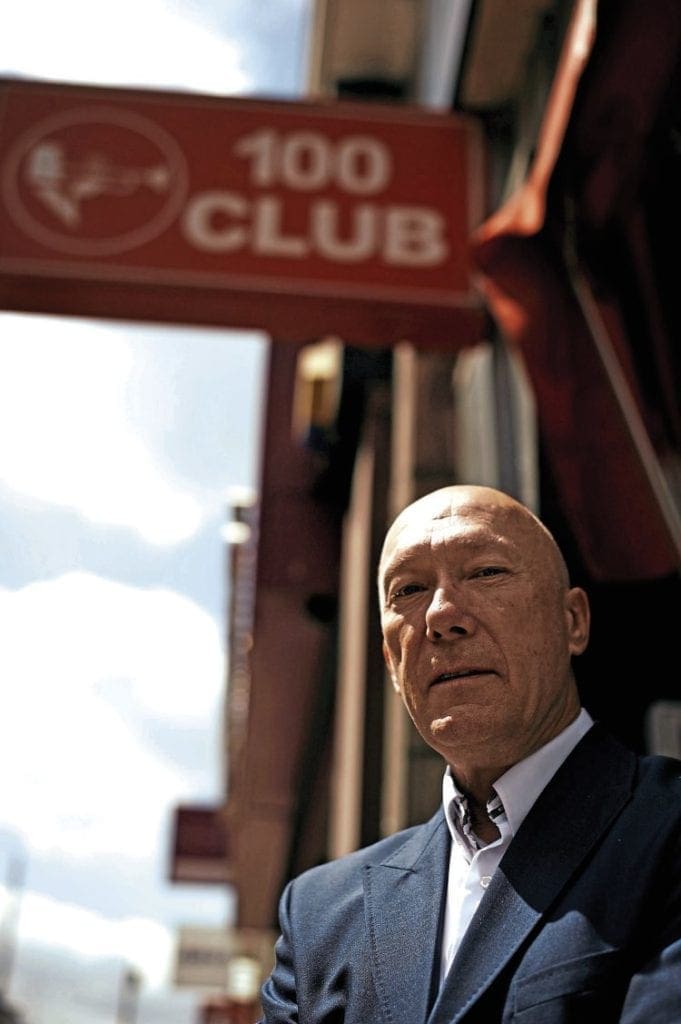

It was while playing a residency at the Nashville Rooms on the corner of Knightsbridge in 1976 that things started to happen for us in London. We started seeing the same faces at our shows, people like Shane MacGowan who was inspired enough to start his own band, the Nipple Erectors, on seeing bands like ours. The Clash also turned up to watch when we were trying to drum-up some press with an impromptu show at Soho Market. By the end of ’75 record companies were beginning to twig there was a bit of a scene going-on and thoughts inevitably turned to who was going to get signed first. Will it be us? The Pistols? The Damned? We were offered a small deal with Chiswick Records which amounted to £600 and free use of a PA or something, but that fizzled out.

Then we were approached by Chris Parry at Polydor, which ended-up with us being invited to record some demos for the ‘suits upstairs’. On the strength of that we were offered a single deal with an option to do an album. I remember being in my mum’s kitchen when I took the call from John to tell us Polydor were going to release a single. From that moment on, everything moved so quickly. We had our first bit of national music press; did our first Top of the Pops; first proper tour and because the single did well, got to record our first album. I gave-up my day job when we were offered the single deal. I was quality controller at an electrical factory, a job I hated ’cause it involved checking components and telling people to ‘do it again’ if it wasn’t right — I wasn’t great at giving orders. Anyway, I went upstairs to tell the head of department I was leaving and the only reaction he gave was, “Oh, well, fine. Off you go then.” It didn’t mean anything to him, he was more worried about filling the vacancy than anything I was going to be doing with the band. As I left, though, I do remember thinking, ‘what happens if the single doesn’t happen? I’m going to be back, knocking on someone else’s door, asking for another job’.

To be someone

After our first Top of the Pops appearance in 1977, I suppose there was a moment when I suddenly went from being Rick Buckler to being ‘that bloke out of The Jam’. You’d walk into a pub, for example, and someone would give you the nod, then they’d walk over to the jukebox and put your record on. It was a bit of a buzz, but also a bit embarrassing. Then it starts to become annoying, ’cause every time you’d walk into a pub they’d put the same bloody record on, which would’ve been In the City at the time. There was no time to dwell on the early success we’d achieved. We were constantly thinking about the next thing we thought we should be doing. That attitude persisted throughout the band’s days, which was no bad thing as it meant we never rested on our laurels.

When it came to our second album, This is the Modern World (released in November 1977) our agenda was completely different to the record company’s. Their attitude was, ‘let’s have another In the City’, but we weren’t prepared to give them that. We wanted to move on, and songs like Life From a Window, and Tonight at Noon proved that. They’re both brilliant songs and far less frenetic than anything we’d done before. They also showed Paul was developing as a songwriter. In the City was easy; we recorded songs we’d been playing for ages. It was different with the Modern World, as some of it was written in the studio during the recording process. It was maybe naivety on our part — we should’ve told the record company to wait till the following year to put a second album out. We were actually quite pleased with the finished article. It still sold reasonably well — it just didn’t come up to Polydor’s expectations. As a band, we were realistic of the fact it was going to take a lot of hard work to become a success, but as we prepared to make our third album, the record company whispers were, if you don’t make it by the third album, that’s it, you won’t make it’. When we played the early demos of the third album to Chris Parry, he took us aside and told us they weren’t good enough, saying something like, “This can’t be another This is the Modern World.” It’s been reported that Bruce had, at the time, considered a career outside of the band if the third album didn’t work out, but I’m not so sure. For me, there didn’t seem any reason to walk away from the band, although in the back of my mind I might have been starting to think, ‘how long is this going to last? Will we survive another single?’

Interview: Andy Gray

Images supplied by: Clicks Photographic Services, and Tony Briggs