Words & Images: Stu Owen

Half a century has now passed since Innocenti released its final piece of scooter design, one that has stood the test of time, achieving legendary status.

Towards the end of the 1960s Innocenti, the producers of the Lambretta motor scooter, put forward bold plans to launch their new flagship model. Not even they knew at the time that it would indeed be their last.

It was a design born out of its predecessors, going way back to the 1950s – which if anything held back its true potential. Even so, it has proved to be a timeless classic as much revered today as at any time since it first rolled off the production line.

Last chance saloon

By 1968 Innocenti had launched a radical new design against the backdrop of the then frenetic space race and branded it as the Luna Line. In its homeland, it was to be called the Lui, while for the UK and export market it was to be known as the Vega.

The engine was taken from the J range series, but the chassis and bodywork layout were completely new. The design was done outside of Innocenti and trusted to Bertone, who by this time had a world-renowned reputation throughout the automotive world.

Though it looked futuristic, one sales slogan calling it ‘The scooter with the year 2000 look’, it failed to capture the public’s imagination. This resulted in poor sales both at home and abroad and put Innocenti, who were already struggling financially, under great pressure.

Both they and Bertone were dismayed by the public’s reaction but vowed to fight on regardless with another new model, which was under development.

By now the SX 200 and SX 150 were keeping sales of the Lambretta alive. They were becoming rather long in the tooth by this time, bearing in mind they had been born out of the Slimstyle range that had first made its debut in 1961.

With a changing and challenging market, not just from rivals Piaggio but also from the ever-increasing threat of the Japanese invasion, it was imperative that Innocenti got things exactly right. The failure financially of the Luna Line had meant the replacement for the SX series must sell strongly from day one of its launch.

Once again, Innocenti put trust in Bertone to come up with the goods. It was different this time around. Instead of designing something from scratch, all he would be doing was tweak something that already existed. The question beckoned: was it possible to take such a classic and well-admired machine in the SX and transform it enough to make it appealing?

The long and short of it was yes, they could with the all-new Lambretta DL. The changes to the chassis were subtle with the only difference being the lowering of the headstock by 1.5 inches. This was clever thinking as it meant the assembly line for the frame would remain virtually unaltered, vastly reducing production costs.

The front would now house a much more compact square headlamp design and with both the leg shields and front mudguard being rounded off, it gave a total transformation to the front of the machine.

The side panels still had the same dimensions as in the past, but would be flat sided and do away with any indents like on past designs. Also for the first time, it would be devoid of any badge work, instead replaced by a black Louvre grill sandwitched between a three-tear stripe. To finish it all off would be a much slimmer seat, which would become known as ‘the coffin’.

Also introduced was a wider and brighter array of colours. For years it was only the side panels that had benefitted from any real colour choice on the Lambretta. This had changed with the introduction of the Luna Line and a few later examples of the SX 150. Now the whole machine would be one colour and far brighter.

White would still be available, but that would complement red, turquoise and ochre yellow. All of these would perfectly offset the black of the side panel stripes and front and rear grills.

Lacklustre ‘DL’

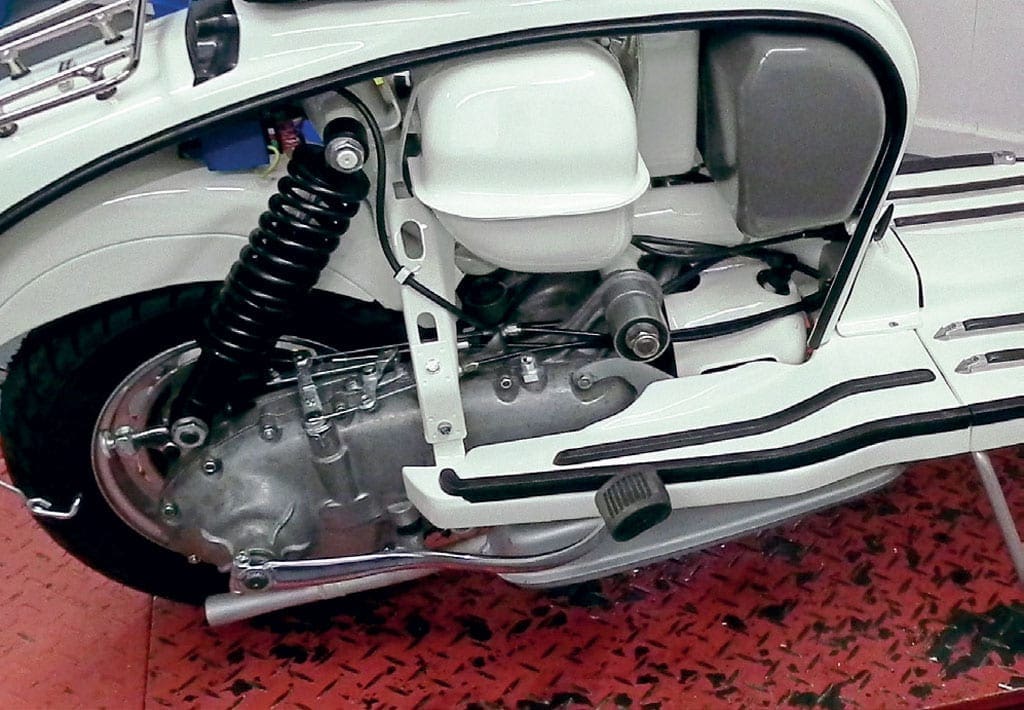

Like every Lambretta introduced over the years, the idea was for the new model to be even better than what it was replacing. Both the 150 and 200cc machines offered more power with greater acceleration and top speed.

This was done by offering a revised top-end design with the biggest change coming by way of a much improved and strengthened crankshaft. Both would come with a 22mm Dellorto carburettor, the biggest Innocenti would fit to a Lambretta, while the 125cc version would have a 20mm version.

The other major change was to the clutch design, which would now incorporate a brass pressure plate to activate it. Both the 150 and 200 would have different gearbox ratios, and this was the only real problem with the 150.

Its gearbox was taken directly from the SX 150 and though it would have relatively close percentage rises on first, second and third gear, the gap to fourth was too big. This meant quite often the rider would have to change down a gear on big hills to stay in the power.

Otherwise, everything remained as it was regarding the electrics, brakes and suspension. This is what worried some within the industry because although overall it looked good, the technology was by this time old and becoming outdated.

Thankfully, Bertone had produced a stunning design and it proved to be a winner with the public, who were somewhat oblivious to its technical short failings. There was a problem though, which was in the name.

The SX sounded good when it came out and rolled off the tongue, whereas the DL didn’t, with some referring to it as a shortening of the word ‘dull’. In the UK this was not going to be the case.

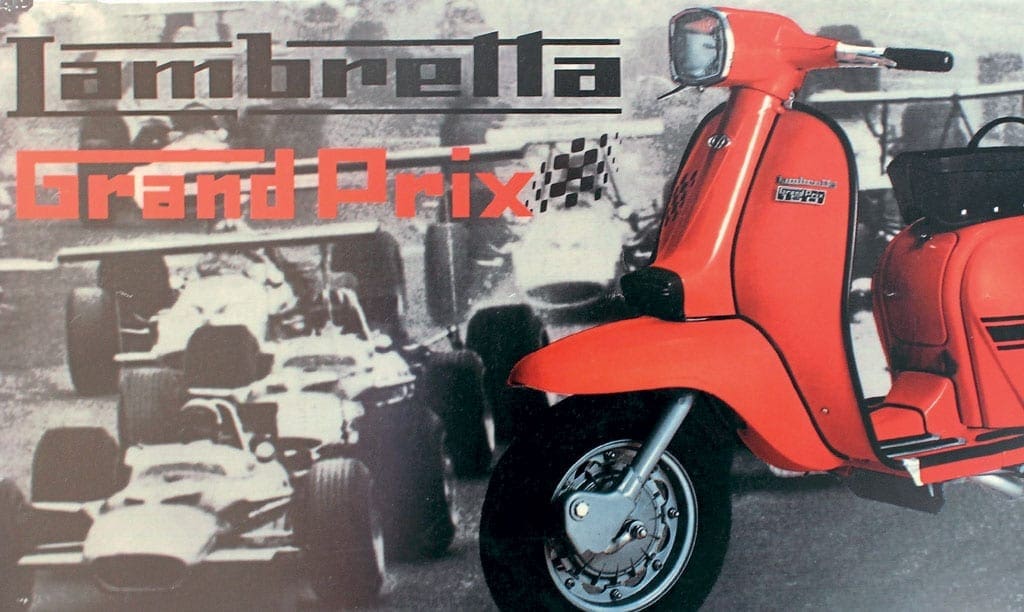

Peter Agg, who had successfully rebranded the Lambretta in the past with the Pacemaker and the GT, was once again going to have his say on the name. With the performance improved and its sleeker and sportier looks, his idea was to name it ‘The Grand Prix’. It was a name that suited it perfectly and one which was associated with speed.

There was no doubt that this had come about through Peter Aggs’ close association with Formula One. Having acquired the Elva sports car company a few years previously and working alongside Bruce McLaren (Mclaren F1), to him it was the ideal name.

He was heavily involved in the sport, even entering a Trojan race car in eight Formula One races a few years later. The idea was an instant winner, so much so that sales were strong, even though the general two-wheeled market was in a rapid state of decline.

UK launch

The first news of the Grand Prix arriving on UK soil was on March 17, 1969, when a technical specification sheet was sent out for both the 150 and 200cc variants. The 125 version wasn’t made available in the UK until the end of the year, when it would finally supersede the SX 150.

It was obvious from figures that both models would be the most powerful and fastest Lambrettas Innocenti had ever produced within those engine capacities. To the dealers who were going to be selling them this was very welcome news. They knew this would have a big impact with customers, who were by now a far more predominantly younger age.

The actual official UK launch was by Lambretta Concessionaires at the International Motorcycle Show in Brighton on April 15, 1969. Both formulas, as Peter Agg liked to call them, again linking them to Formula One, were proudly put on display for all to see.

Orders came in thick and fast and for a while it looked as if sales would go back to how they were in the past glory days. Unfortunately in Italy, with the growing industrial action widespread across the country, production was heavily hit.

In what was known as ‘the hot autumn’ of 1969, it would see the Innocenti factory in permanent lockdown for a period of nine months. It was a frustrating time, with sales of the Grand Prix so strong only to be held back due to lack of production. Even after the strike was over and supplies began rolling out of the factory once again, Innocenti couldn’t keep up with demand.

In February 1971 a new ignition system was incorporated to the GP 200. From now on it would be fitted with an electronic ignition system, replacing the old tried and tested points layout that had served the Lambretta since its inception in 1947. This was not actually a development by Innocenti themselves, but by Ducati who had been the main ignition supplier during the past.

The system was designed around their motorcycle production, but seen as a direct replacement for the Lambretta. In Italy, the DL would have the ignition fitted with the only other noticeable feature, a silver sticker on the front leg shields displaying the fact. For UK models the seat would be replaced with a much wider and taller shaped one instead.

The end is nigh

By 1971 and with Innocenti in a perilous financial position they were finally taken over by British Leyland in May of that year. One of the new owner’s first decisions was to stop Lambretta production in its entirety, so drawing the curtain down on the Grand Prix with immediate effect.

The GP 200 Electronic had only been available for three months (longer in Italy), so only several hundred were ever built. To this day the actual figure of exactly how many were made is regularly subject to speculation and the truth is we will probably never know.

The assembly line of the Grand Prix was sold off to India the same year, where production would carry on into the 1990s. The quality of the Indian examples has never been regarded as good as what Innocenti produced, and though still widely used, they are not held in such wide esteem.

In saying that, without the Indians continuing production the availability of both machines and spares would be almost impossible. There is no doubt they have helped immensely in still keeping the Grand Prix on the road over the last 50 years, and this should never be forgotten.

Legendary status

The Grand Prix was just one of many models that were produced by Innocenti, and while some like it, others are not so keen. Those that don’t see it as a bit too modern with its square headlamp and the use of plastic within its make-up. It must be remembered that the Grand Prix was created by modifying an existing design and aesthetically making it look better.

Even all these years later the shape and contours of the bodywork look modern and stylish, even in today’s world. Unfortunately, the engineering isn’t and belongs well in the past, but it’s a problem which devotees are prepared to put up with.

It was always going to be a popular model from a sporting side with its lower front end and slightly more compact design. Even today the Grand Prix is widely used in both track racing and sprinting. It’s almost impossible to work out how many have been crashed or damaged one way or another through racing. Then there was the custom scene explosion of the 1980s which, if anything, is still as strong, with its flat side panels the ideal canvas for professional painters to weave their magic on.

No one is saying other Lambretta models can’t be raced or customised, but when it comes to the Grand Prix it defiantly has preference over everything else. For the Lambretta street-racer the Grand Prix has to be the ultimate choice, and this harks back all the way to Peter Aggs’ idea of naming it so in the first place –a name that is associated with the pinnacle of motorsport and performance.

The Grand Prix model that is by far the most talked about is the GP 200 electronic. Questions are still raised from how many were made to what was actually the earliest known. Unfortunately, the only real difference on the electronic frame compared to a points type one is the mounting plate for the CDI unit.

Over time there have been one or two that have had plates welded in order to disguise the fact. While this is not the right thing to do, by using an earlier frame this could tamper with historical facts regarding frame numbers. Thankfully, the plate was spot welded on in the factory and copying it the way it was done is almost impossible to do, thus eliminating the majority of doctored frames from the equation.

Since its introduction in 1969, the Lambretta Grand Prix has been ever-present. One must wonder what would have happened if the factory had carried on and so to model development.

Would the Gran Prix itself have been upgraded, or would something entirely new have been designed? That is a question we will never know, and by the factory finishing production when it did, this instantly gave the Grand Prix an iconic status, one that has lasted for half a century and one that will carry on almost indefinitely into the future.

Did you buy a brand new Lambretta Grand Prix in 1969 or up until production finished in 1971? If so, we would love to hear your story.