In 1965 a young taxi driver from Bristol set about breaking a world speed record on a Lambretta… one that has since created huge controversy.

In the mid-1960s the popularity of the scooter was in a slow but sure decline, with manufacturers needing to create media interest in any way they could to try and draw attention to their products.

One such idea that was thought up is still to this day surrounded by controversy and many unanswered questions. It was simple enough: to break a world speed record on a Lambretta, but it went much further than just that. By using a female rider which, back then, was frowned upon, it would create huge media interest in the project from the outset – possibly more than the attempt itself.

With the challenge laid down, the task of building the machine got under way and so did the selection process for the rider. Slowly dragged out over several months during 1965 and with the attention of leading national newspapers, it got the publicity those involved were looking for. Towards the end of the year, the attempt was finally made and that is where all the controversy surrounding it really started.

What we do know

The Lambretta used was a modified TV200 which was stripped of its bodywork and top shell, using the mainframe tube as a seat which allowed the rider to sit in what is known as the kneeler position. The forks and headset were significantly lowered with a set of clip-on handlebars attached to the front forks to enable it to be steered. The engine used the original TV200 cylinder which was bored out to give a capacity of 225cc and fed through a Wal Phillips fuel injector.

The frame was enclosed by an aerodynamic front fairing with a separate one at the rear. In some pictures of the actual attempt the rear fairing was removed, which may have been down to the conditions as certain wind directions can make a two-wheeled machine very unstable when a fairing was fitted.

Innocenti, Filtrate and Lambretta Club Great Britain

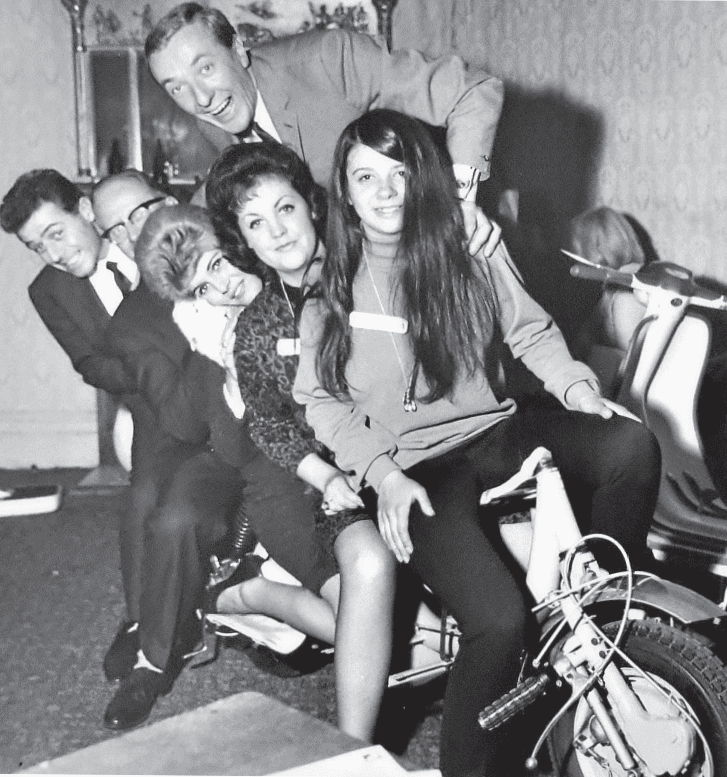

Lambretta Concessionaires with input from Lambretta Club Great Britain, the other main interest coming from oil company Filtrate. Women Lambretta riders only were asked to apply to be the pilot and in total 67 entrants put their names forward. Over several months and carefully choreographed press meetings along the way the number was slowly whittled down to just a few, in the end, Marlene Parker being the chosen rider for the seat. Throughout the whole selection process, the media press attention was huge and this is what Peter Agg, head of Lambretta Concessionaires, wanted all along.

Bob Wilkinson, who was head of the company’s PR department, commented in later years he wasn’t interested in the project as Lambretta Club Great Britain was his main concern even though he had to be involved in the selection process. He remembers Peter Agg not paying much attention to the attempt either as he was so busy running the company and had already got the publicity he wanted out of it.

The selection process was slowly whittled down to 12 women, then the final three: Marlene Parker, Christine Jackson and Pat Cowburn. According to the press at the time, a white glove had three pieces of paper screwed up inside it with the name Monza inscribed on one of them. Marlene was the first to draw out of the glove and picked the one with Monza on it, giving her the seat. She was 22 years old at the time and lived in Bristol working as a taxi driver.

The machine, named Atlanta V, had been built, but it was rather a rushed process and the first planned test at Snetterton racetrack in early November 1965 was cancelled due to bad weather conditions. Around the same time, Don Noyes had been breaking UK speed records on a modified full-frame TV200, the inspiration for this project in the first place. At an undisclosed track for the first real test, Don Noyes turned up and he invited Christine Jackson, who didn’t get the Atlanta V seat, to have a go on it. She recalls riding both the Atlanta V and the Don Noyes TV200, named Stingray, at the venue that day and being much faster on Stingray, establishing a new record in the process.

The actual attempt was done on December 2, 1965 at Monza racetrack in Italy with certified officials there to record the speed. Reports from the day said the engine had starting issues and a constant misfire. It must be remembered the engine used the Phillips fuel injector which was notorious for bad starting and the kick-start had been removed, meaning it had to be bump-started making the process even more difficult. Several runs were made on the day with one resulting in a high-speed seizure, almost throwing Marlene from the machine.

What we think we know

Regarding the machine itself, Robert Forrest-Webb, along with Alan Healy, were the two people responsible for building it at a reported cost of £1000 with reported input from Ernie Hall. This is where the confusion starts because Bob and Ernie were employed by Filtrate and it was reported it was the company they worked for who had the idea to do the attempt with them leading it.

There is also a claim by a man named David Lloyd saying he worked on the project and met Marlene Parker on several occasions. No other person has ever been mentioned regarding working on the Atlanta V machine apart from these four people. Several GT200s were supplied to the team which had to come from Lambretta Concessionaires, and this would explain what at the time was a huge cost to build it and certainly their involvement.

Apart from Lambretta Concessionaires and Filtrate it is claimed the Daily Express newspaper, Dell’Orto Carburettors and Wal Phillips fuel injectors backed the project. After more research, several articles referring to the attempt were published in the Daily Express so their involvement can now be verified.

The actual results of the attempt are shrouded in mystery and over the years have been rife with exaggeration. According to some press reports at the time, Marlene reached a top speed of 110mph and over the years quotes of up to 130mph have been bandied around, also claiming world records. Other reports said it was a complete disaster and only one run of around 80mph was achieved. To gain an official world record attempt it is done in opposite directions over a one-hour time period with the mean (average) time and speed taken. It is not known whether Marlene did this or just several one-way runs.

It is also alleged because the project was rushed and with a lack of testing beforehand, she was plagued by constant mechanical problems and issues on the day which resulted in many aborted runs. Regarding the claim that she did establish a new record, this was never ratified at the time because women were not allowed to enter the discipline officially. There are no documents available anywhere currently in the lists of official records which include Marlene Parker on Atlanta V.

What we don’t know

The main thing we don’t know is the whereabouts of Marlene herself, who since that time seems to have completely disappeared, despite several attempts to find her. If she is still alive, she would be in her late 70s now and the only person able to explain what really happened. Regarding the top speed Atlanta V reached, it is still a mystery as there are no official records anywhere and just hearsay and exaggerated press reports which are not physical proof.

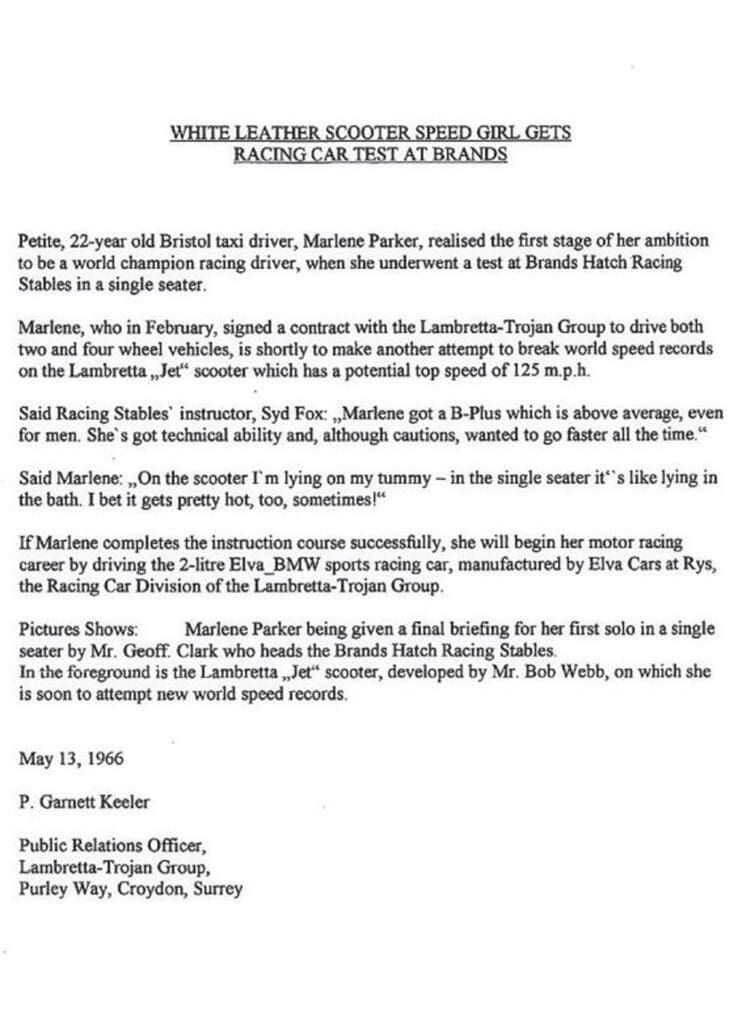

With the attempt at Monza being such a disaster the team decided to go back to the drawing board and make improvements alongside full testing. It was then reported Marlene would have a second go at Monza in the spring of 1966. The second attempt never happened; there has never been an explanation as to why.

The ACU in Britain and FIM, the world governing body of the records, stepped in and tried to deny Marlene getting the required licence to attempt the record because she was a woman. It was reported that a male rider would step in if necessary, but who was he? No one knows. Sometime after this date, Atlanta V was sold to Arthur Francis but it was, according to him, minus its engine, with Arthur building a new one so he could use it for sprinting.

The question remains: what happened to the engine and where did it go? Does it still exist? Apart from the four names already mentioned regarding building the machine, were others involved? The cylinder, for instance, was heavily tuned – but who did it?

At that time there weren’t many shops or tuners offering such services and this remains a big mystery. We know the Rallymaster which came out in 1961 had a slightly tuned cylinder and was carried out at the Trojan works where Lambretta Concessionaires was based. Also, building sports cars and race engines there, was it someone who worked at the factory that carried the work out, or Robert Forrest-Webb himself?

Where is it now?

After the attempt Arthur Francis bought Atlanta V, as already stated, minus the engine; the whereabouts of the aerodynamic fairings also remains a mystery. It had the small front motorcycle fairing intact which was used in the test before the main fairings were added. Arthur then passed the machine on to Mike Karslake where it was displayed in his museum until that was disbanded in 1994. Scooter Center Cologne (Köln) purchased it from the auction at the museum when all the exhibits were sold off and after carrying out a sympathetic restoration it is now on display in their shop.

Things which don’t quite add up…

During the build-up to the attempt all through 1965, the media attention as we know was great and was planned to be like that. Lambretta Concessionaires throughout their history, both before and after Atlanta V, regularly sent out press releases for anything regarding publicity surrounding the Lambretta.

Given that this was the biggest opportunity they ever had, strangely, there were no press releases of any kind from the factory in the months before. Having allegedly broken a world record and achieved the claimed speeds there was nothing mentioned by the company afterwards apart from a press release in May 1966 saying there would be an official world record attempt on the machine which was now named Jet. It seems odd that there was almost a complete media blackout from the company regarding it.

Also, the Daily Express, which was keen to report on Atlanta V all the way up to the event, went very cold on it afterwards and then ran only a brief piece about Marlene Parker three months later. Surely if it did what was claimed, both Lambretta Concessionaires and their backer the Daily Express would be singing from the rooftops about it. Also, rather than leave it abandoned and sell it off without its engine you would have expected it to be preserved and on display at the company’s headquarters.

Appeal

Though there is a lot of information on Atlanta V there are still many unanswered questions. Does anyone know the whereabouts of Marlene Parker or those involved – Robert Forrest-Webb, Alan Healy, Ernie Hall and David Lloyd? Does anyone know of others who were part of the team, either building it or just helping?

What about the actual attempt in Monza – is there any information regarding that or the testing in the UK? Then there are the 67 women who put themselves forward to ride it, do any of them have a story to tell and does anyone know who they are or their whereabouts?

Press releases are also extremely helpful and having looked through the biggest archives available, nothing has been found apart from the one letter after it was renamed Jet. Does anyone have any kind of paperwork relating to it, even newspaper clippings? There were a few in the scooter press but all repeat the same story. Anything that relates to the Atlanta V story that sheds new light on it is worth following up to find the missing answers. So, if anyone has any information, please contact us at the magazine. Who knows, you may help in solving one of the biggest scooter myths of all time…

Words: Stuart Owen

Extra information and photographs: Thanks to Stan Bates, Philipp Montforts, and Mortons Archive